ABOUT US

We are security engineers who break bits and tell stories.

Visit us

doyensec.com

Follow us

@doyensec

Engage us

info@doyensec.com

Blog Archive

© 2026 Doyensec LLC

This article shares our perspective on the current state of authentication and authorization in enterprise-ready, remote MCP server deployments.

Before diving into that discussion, we’ll first outline the most common attack vectors. Understanding these threats is essential to properly frame the security challenges that follow. If you’re already familiar with them, feel free to skip to the section “Enterprise Authentication and Authorization: a Work in Progress” below.

Huge shoutout to Teleport for sponsoring this research. Thanks to their support, we have been able to conduct cutting-edge security research on this topic. Stay tuned for upcoming MCP security updates!

At this stage, introducing the Model Context Protocol (MCP) would be redundant since it has already been thoroughly covered in the recent surge of security blog posts.

For anyone who may have missed the conversation, here’s a brief recap:

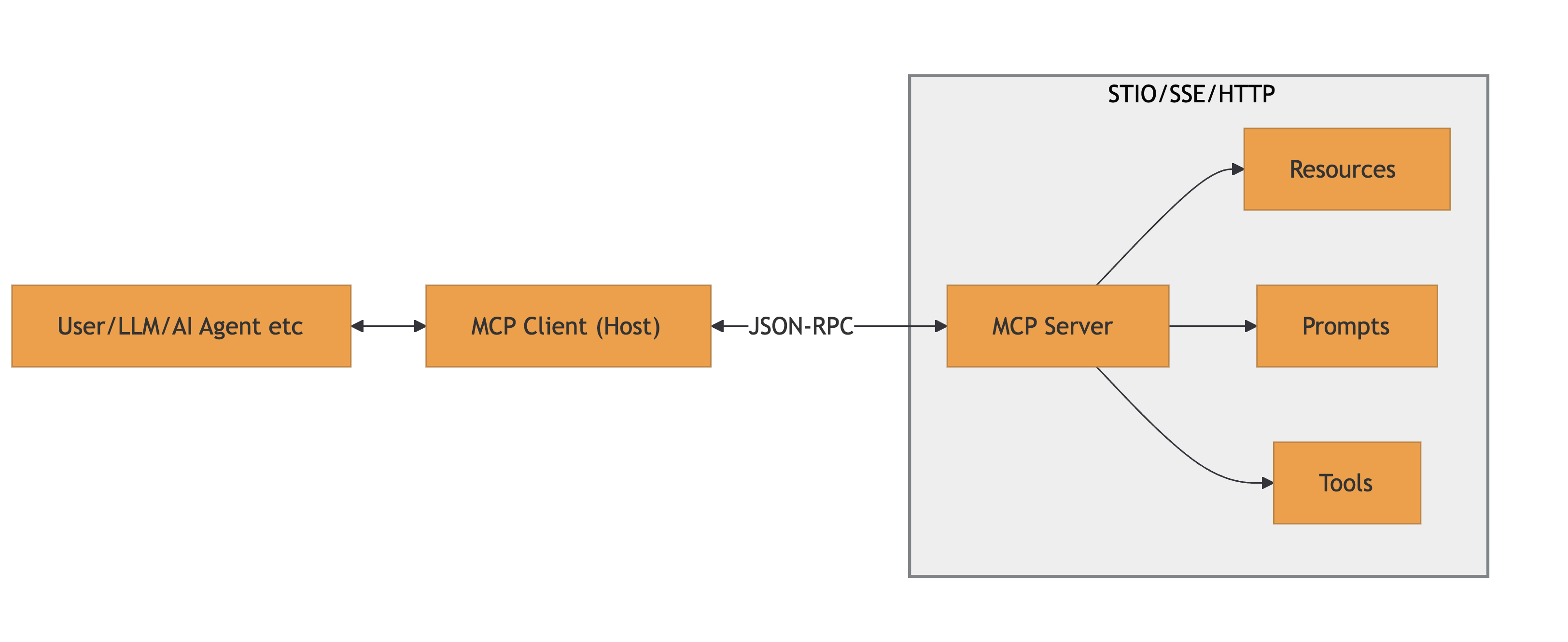

MCP is a protocol used to connect AI models to: data, tools and prompts. It uses JSON-RPC messages for communication. It’s a stateful connection where clients and servers negotiate capabilities.

A high-level architecture is provided below:

References: MCP Specification and MCP Architecture

Several categories of vulnerabilities pertaining to MCP emerged in the wild. While it might not fit every bug you read about, as things are changing on a daily basis, a good starting point is the good and not-so-old OWASP MCP Top 10.

Below are the most relevant vulnerabilities we have encountered so far, organized by the malicious actor profile:

Rogue MCP servers could intentionally exploit clients with:

tools/list call, then switches to malicious ones during execution or in subsequent MCP messagesIt should be highlighted that the the listed attacks are exploitable by either local or remote MCP servers. Of course, the outcome varies drastrically in terms of achievable impacts.

Rogue MCP clients could intentionally exploit servers with:

CVE-2025-53100 (RestDB’s Codehooks.io MCP Server), CVE-2025-53818 (GitHub Kanban MCP Server)Beyond the traditional client-server factors, an MCP ecosystem could also be compromised by:

.well-known/oauth-authorization-server) and dynamic client registration. Malicious actors could exploit these intermediaries by injecting fake metadata, manipulating redirect URIs, or compromising the registration endpoint to obtain unauthorized client credentials (e.g., CVE-2025-4144 - a PKCE bypass in workers-oauth-provider, CVE-2025-4143 - improper redirect_uri validation)Securing SSO remains an open challenge for the industry due to its intrinsic complexity. The past few years have highlighted this reality, with a steady stream of severe vulnerabilities affecting OAuth2, OIDC, SAML and SCIM implementations.

Yet, progress never stops and authentication & authorization in MCP are the new inevitable nightmare. Being a relatively new protocol, the standards for how clients and servers should establish trust are still evolving, leading to a fragmented ecosystem.

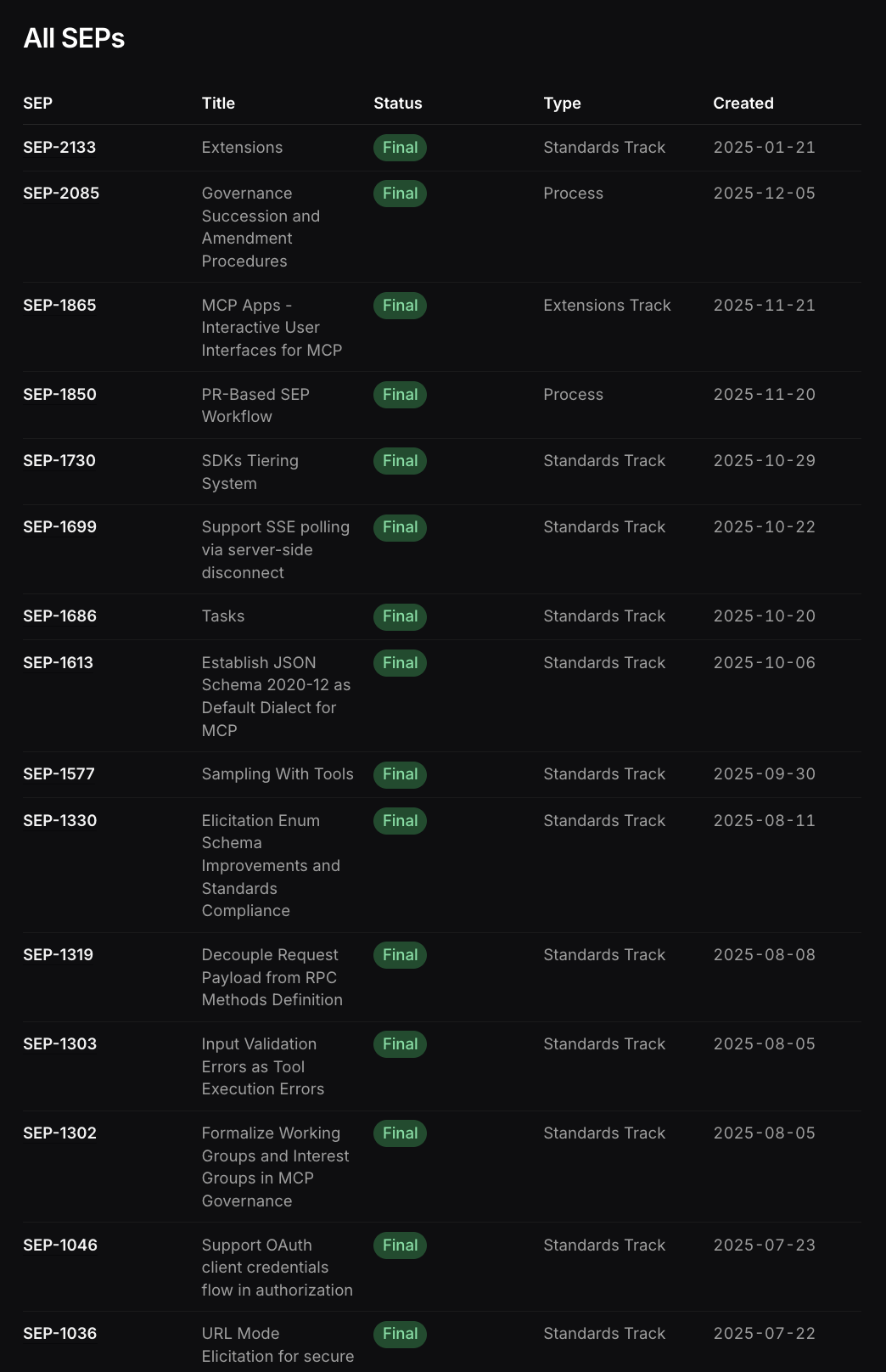

The specifications for AuthN/AuthZ are subject to continuous changes and extensions, as is common for newborn protocols. This instability means that today’s “secure and compliant” implementation might be deprecated or insufficiently secure tomorrow.

Just few of the latest Specification Enhancement Proposals (SEPs) in MCP

Multiple significant issues have been emerging in the MCP SSO implementation, many as descendants of the common OAuth2/OIDC vulnerabilities, but also new ones.

We have seen browser-based clients or open() URL handlers exploited to launch arbitrary processes or redirect to malicious servers, showing the fragility of the MCP client-side implementation, often linked to automatic action executors.

Then, attacks against the new metadata discovery and old-school metadata endpoints:

Notable mentions around the cited scenarios are: CVE-2025-6514, “From MCP to Shell”, CVE-2025-4144, CVE-2025-4143, CVE-2025-58062

Furthermore, many implementations (like IDE extensions and CVE-2025-49596) assumed localhost was secure, starting WebSocket servers without auth, allowing any local process (or malicious website via DNS rebinding) to connect.

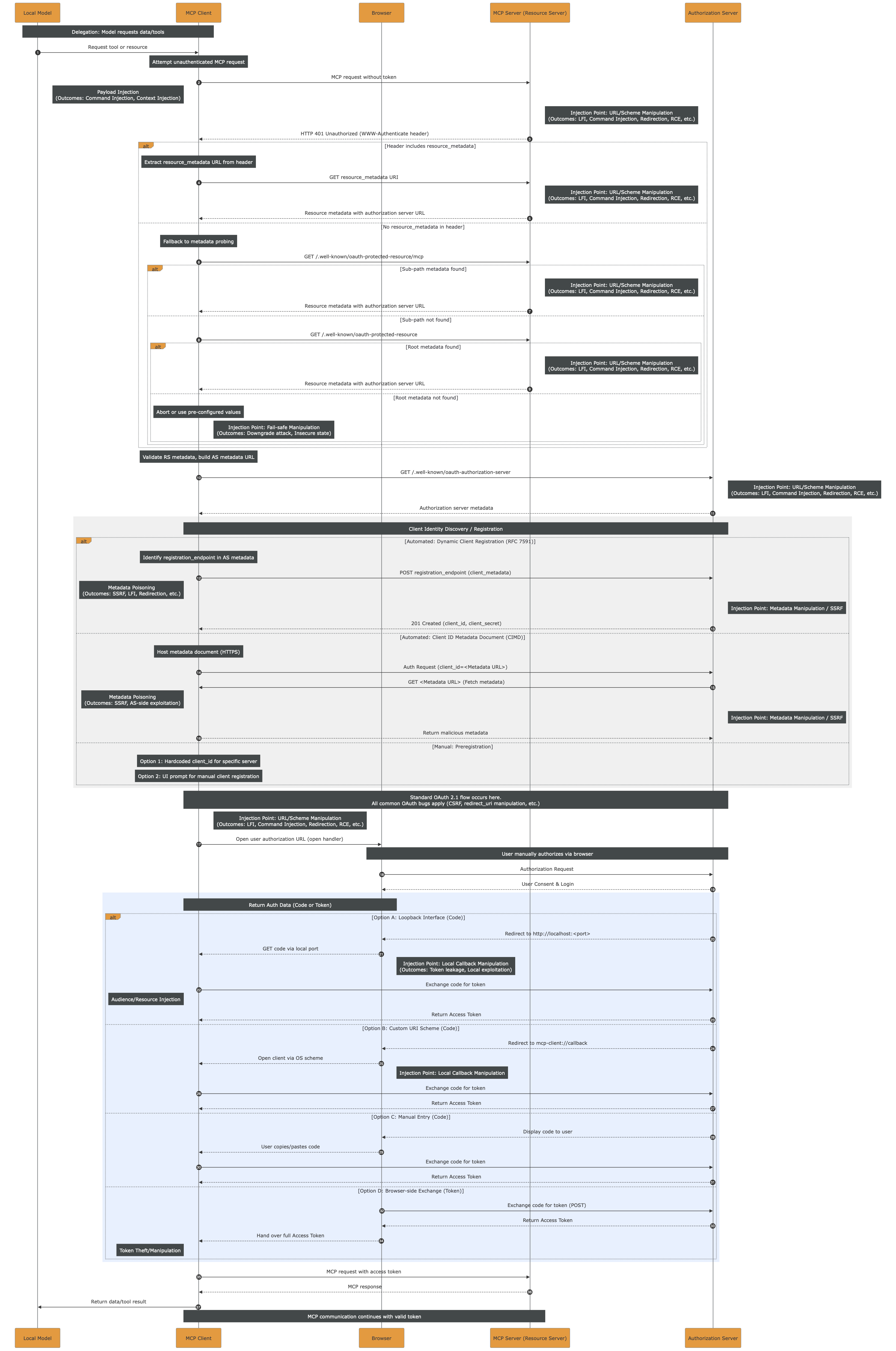

While keeping up with the latest news is pretty complex, time consuming and not always possible, we attempted to sum-up the potential injection points affecting the current MCP Authentication via OAuth2 and dynamic client registration.

The monolith sequence diagram below embodies the title of this post. It should serve as a reminder of how extensive the attack surface is and how many injection points exist. One could argue that “every step is an injection point” and that would not be inaccurate. However, the goal here is to illustrate the full length of the authorization flow, from start to finish, highlighting the many branches, variations, and opportunities for subtle yet impactful vulnerabilities.

The high-resolution PDF file can be downloaded here.

While prompt injection requires a different approach, most of the injection points and impactful outcomes, such as LFI, RCE, etc. could be prevented by strictly applying sanitization and validation of the inputs. Still, the monolith highlights how complex it is to do so, given the length and variety of actors throughout the entire flow.

In the OAuth specification, there is scope consent by the user at the time of authorization.

The user HAS to see and approve the exact scopes for each third-party tool/app/etc. before any token is issued by the IdP.

Currently, there is no homogeneous way to manage MCP security across an enterprise. While individual MCP tools struggle with authentication and often just rely on secret tokens, the Enterprise-level authN/Z is a whole other challenge.

In fact, in enterprise-managed authorization the scope consent is decoupled from the time of authorization.

As an example, an MCP client with enterprise authorization could be accessing Slack and GitHub on behalf of the user, but the user never explicitly consented to

github:readslack:writein a consent screen. The local agent decided the task and the scopes required, and the enterprise policy enforcement decided to allow it on behalf of the user based off their MCP Client identity.

Down that path, there is intermediary tooling trying to offer a partial solution such as MCP Proxies/Gateways. While they are extremely useful at aggregating MCP severs under the same centrally-managed authentication and authorization layer, they are still not solving the problem rising with dynamic scopes and plug-and-play third-party tools/apps.

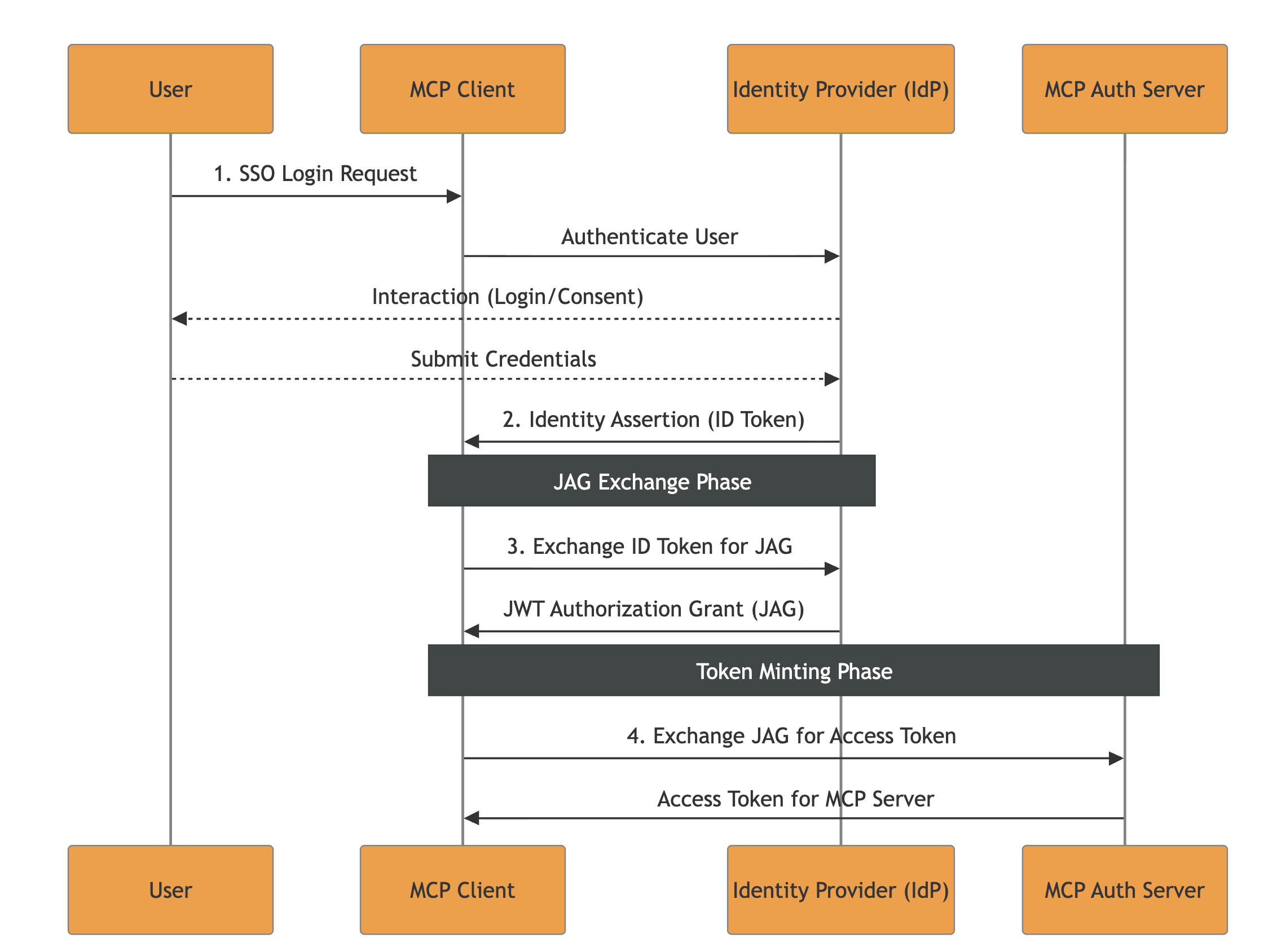

On the other side, there are active discussions around a native Enterprise-Managed Authorization Extension for the Model Context Protocol. During our research on the matter, we had the possibility to do a deep dive into a current draft of the extension, which relies on the Identity Assertion JWT Authorization Grant (JAG). Given our exposure to real-life security engineering challenges faced by our clients, we decided to take a step further and offer our feedback on the draft. We strongly suggest reading the Extension Draft and Doyensec’s pull-request with the updated Security Considerations.

The following summarizes the JAG approach and our considerations. For readers interested in understanding all the aspects in great depth, we would recommend reading the full draft before continuing.

The main idea of this specification revolves around leveraging existing Enterprise Identity Providers (IdPs), such as Okta or Azure AD.

The flow’s key-points are:

The current specification introduces a few outstanding challenges:

1. Access Invalidation Problem

There are three level of tokens issued throughout a correct execution of the flow:

The proposed specification does not explicitly describe mechanisms for invalidating access to an MCP client or revoking issued tokens / ID-JAG.

MCP-Specific Note: While the access invalidation is also unspecified in the parent RFCs, the high risk associated with non-deterministic agentic accesses to tools and resources should require an access invalidation flow for the Enterprise context. Otherwise, the enterprise processes being authorized with the above mentioned spec would not have a clear emergency recovery pattern whenever agents start misbehaving (e.g., injections and other widely known attacks). Consequently, every actor could end-up proposing its own recovery pattern, bringing ambiguity and implementation differences.

2. LLM Scope Abuse Without User Consent

In JAG, the IdP issues an ID Token with no scopes embedded. It just states the identity of the user to allow impersonation from the MCP client. When the MCP client requests a JAG for high-risk scopes like github:write slack:write, no consent pop-up is triggered. The enterprise policy decides on behalf of the user being impersonated.

MCP-Specific Note: While this is totally normal in a classic Machine-to-Machine (M2M) environemnt where the enterprise users are expected to be directly mandating specific tasks on their behalf to automation software, that standard does not apply to the MCP field.

The tasks and actions list being transformed into MCP interactions are not directly chosen deterministically from the end-user.

In general, the consent requirement bypass offered by JAG would allow LLMs to autonomously request any scope permitted by enterprise policies, even if it’s irrelevant to the user’s current task, removing the human-in-the-loop for high-risk actions.

3. How the IdP Creates, Distributes and Validates Clients

Within the JAG proposal, it is not declared how the IdP should issue/distribute client credentials (secret vs. private-key JWT vs. mTLS, how they’re delivered, rotation, etc.).

Moreover, it is not declared how important it is for the IdP to ensure that the audience (The Issuer URL of the MCP server’s authorization server) is linked to the resource (The RFC9728 Resource Identifier of the MCP server).

MCP-Specific Note: While such a practice is unspecified in the parent specifications, enterprise architectures are usually based on multiple IdPs managing access to a wide range of resources, often overlapping: e.g., both IdP A and IdP B can authorize access to app C. Within the presented Enterprise MCP scenario, multiple IdPs could be authorizing multiple MCP Authorization Servers (often overlapping), while each of them manages scopes for a range of MCP Servers.

In such context, clearly defining namespaces and required checks on IdPs and MCP Authorization Servers would help preventing implementation issues like:

- Scope Namespace Collision: If Server A and Server B both use common scope names like

files:read,admin:write, etc., the attacker could leverage a low-privilege ID-JAG from Server B to gain access to Server A ifaudis not checked to be the Authorization Server and theresourceas one of the MCP Servers managed by the specific MCP Authorization Server- Resource Identifier Injection: If the MCP Server Authorization Server doesn’t validate that the

resourceclaim in the ID-JAG matches its own registered resource identifier, it cannot distinguish between ID-JAGs intended for different servers. Once obtained an MCP session, the injected value could be lost and irrelevant, allowing cross-access.The IdP must ensure that JAGs for resources not managed by the caller client are not forged.

4. ID-JAG Replay Concern

Whenever a single ID-JAG can mint multiple MCP Server access tokens, and those access tokens can invoke high-impact tools, then the ID-JAG becomes an amplifier of damage. That is why the decision of enforcing single-use checks on the jti should belong within the specification.

Authentication and authorization, especially in the context of SSO and transitive trust across third parties, have historically been a breeding ground for subtle, high-impact vulnerabilities. MCP does not change this reality. If anything, by introducing additional layers of indirection, remote server pooling, and agent-driven workflows, it amplifies the existing complexity. In the near term, we should expect AuthN/Z in MCP deployments to remain a challenging and error-prone domain.

For this reason, both auditors and developers should apply the strictest possible validation at every step of any SSO flow involving MCP. Token issuance, audience binding, scope enforcement, session propagation, identity mapping, trust establishment, and revocation logic all deserve explicit scrutiny. The end-to-end sequence diagram presented in this article is intended as a practical starting point: a tool to reason about the full authorization chain, enumerate trust boundaries, and systematically derive a security test plan. Every transition in that flow should be treated as a potential injection point or trust confusion opportunity.

When it comes to enterprise-managed authorization models, approaches such as JAG raise significant concerns. They introduce complex cross-specification dependencies, expand the number of actors involved in trust decisions, and substantially widen the attack surface. More critically, the model’s reliance on full user impersonation by non-deterministic agents, capable of autonomously selecting and executing tasks without explicit per-action user consent, is misaligned with MCP’s security requirements. Delegation without tight contextual constraints is indistinguishable from privilege escalation when boundaries are not rigorously enforced.

Based on our experience, a more robust direction for enterprise MCP deployments would emphasize strong, explicit trust anchors and protocol minimization. Technologies such as certificate-based authorization and mTLS, adapted specifically to MCP’s interaction model, provide clearer security properties and reduce ambiguity in identity binding. These mechanisms should be complemented by:

In short, the goal should not be to replicate the full complexity of traditional enterprise SSO stacks inside MCP, but to reduce implicit trust, constrain delegation semantics, and make authorization decisions auditable and deterministic.

If the industry has learned anything from the past decade of OAuth, OIDC, SAML, and SCIM vulnerabilities, it is that complexity without strong invariants inevitably leads to security gaps. MCP deployments would do well to internalize that lesson early.

In cooperation with the Polytechnic University of Valencia and Doyensec, I spent over six months during my internship in a research that combines theoretical foundations in code signing and secure update designs with a practical implementation of these learnings.

This motivated the development of SafeUpdater, a macOS updater vaguely based on the update mechanisms used by Signal Desktop, but otherwise designed as a modular extension.

SafeUpdater is a package designed for MacOS systems, but its interfaces are easily extensible to both Windows and Linux.

Please note that “SafeUpdater” is not intended to be used as a general-purpose package, but as a reference design illustrating how update mechanisms can be built around explicit threat models and concrete attack mitigations.

⚠️ This software is provided as-is, is not intended for production use, and has not undergone extensive testing.

A software update is the process by which improvements, bug fixes, or changes in functionality are incorporated into an existing application. This process is crucial for maintaining the security of the app, improving performance, and ensuring compatibility with different systems. Because updates are central to both the maintenance and evolution of software, the update mechanism itself becomes one of the most sensitive points from a security perspective.

In Electron applications, an updater typically runs with full user privileges, downloading executable code from the Internet, and may install it with little or no user interaction. If this mechanism is compromised, the result is effectively a remote code execution channel.

Being one of the most widely used application frameworks for desktop apps, Electron also represents one of the most attractive targets for attackers. While the official framework update mechanism provides a ready-to-use solution for most applications, it doesn’t protect against certain classes of attacks.

Currently, there are two main solutions for implementing an auto-update system in ElectronJS:

The first is the built-in auto-updater module provided by Electron itself. This module handles the basic workflow of checking if there are updates available, downloading the update, and applying it, using standard HTTP(S) and relying on code signing and framework-specific metadata for file integrity.

One of the simplest ways to use it is with update-electron-app, a Node.js drop-in solution that is based on Electron’s standard autoUpdater method without changing its underlying security assumptions. The following code snippet shows an example of its implementation:

const { updateElectronApp, UpdateSourceType } = require('update-electron-app')

updateElectronApp({

updateSource: {

type: UpdateSourceType.StaticStorage,

baseUrl: `https://my-bucket.s3.amazonaws.com/my-app-updates/${process.platform}/${process.arch}`

}

})

This module builds on top of Electron’s autoUpdater, providing a higher-level interface:

autoUpdater.setFeedURL({

url: feedURL,

headers: requestHeaders,

serverType,

});

The second solution is using Electron-Builder’s electron-updater library, which offers a more integrated approach for managing application updates. When the application is built, a release file named latest.yml is generated, containing metadata about the latest version. These files are then uploaded to the configured distribution target.

The developer is responsible for integrating the updater into the application lifecycle and configuring the update workflow.

| Feature | Electron Official (autoUpdater) |

Electron-Builder (electron-updater) |

|---|---|---|

| Publication server requirement | Requires self-hosted update endpoints | Uses built-in providers (e.g. GitHub Releases) |

| Code signature validation | macOS only | macOS and Windows (custom and OS validation) |

| Metadata and artifact management | Manual upload of metadata and artifacts required | Automatically generates and uploads release metadata and artifacts |

| Staged rollouts | Not natively supported | Natively supported |

| Supported providers | Custom HTTP(S) only | Multiple providers (GitHub Releases, Amazon S3, and generic HTTP servers) |

| Configuration complexity | Higher, especially with a custom server | Minimal configuration |

| Cross-platform compatibility | Platform-specific tools (Squirrel.Mac, Squirrel.Windows) | Unified cross-platform support (Windows, macOS, Linux) |

Now that we have a clear picture of the software update mechanisms available in ElectronJS today, we can shift our focus to two specific threats that are not mitigated by any of the existing open-source solutions. It is worth noting that most of the considerations discussed here are not specific to ElectronJS itself, but apply more broadly to software updaters for desktop applications in general.

At the core of these issues lies a fundamental limitation of modern operating systems: the lack of a reliable, built-in mechanism to fully validate the integrity of the software currently running on the system. While macOS, thanks to its relatively closed ecosystem, does provide native capabilities such as code signing and notarization to help verify software integrity at runtime, this is not the case on Windows. As a result, Windows applications cannot rely on the operating system alone to assert that the updater or the application binary has not been tampered with.

Because of this gap, software updaters must implement additional safeguards and workarounds to compensate for the missing integrity guarantees. These compensating controls are often complex, error-prone, and inconsistently applied across projects, which ultimately leaves room for entire classes of attacks that remain unaddressed even in the most popular desktop applications.

In all software updater implementations, the following assets are considered critical and must be protected:

In this post, we focus only on the threats that are not mitigated by the default ElectronJS software update mechanisms. In fact, given the absence or limited capabilities around software integrity checks at the OS level, the following threats remain unaddressed:

| Threat | Attack Vector | Threat Actor | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Downgrade (Rollback) Attack | Manipulation of update manifest or version metadata to serve older releases | Malicious third party, MITM (Man-in-The-Middle), compromised server | Reintroduction of known vulnerabilities |

| Integrity Attack | Tampering with update binaries, installers, or metadata | MITM (Man-in-The-Middle), compromised CDN, update server, or build pipeline | Arbitrary code execution |

| Race Condition Attack | Replacing verified update files between verification and installation | Local attacker with system access | Execution of malicious code, privilege escalation |

| Untested Version Attack | Serving signed but non-production (alpha/beta/dev) builds via update channel | Malicious third party, MITM (Man-in-The-Middle), insider threat | Exposure to unreviewed features, debug functionality, or new vulnerabilities |

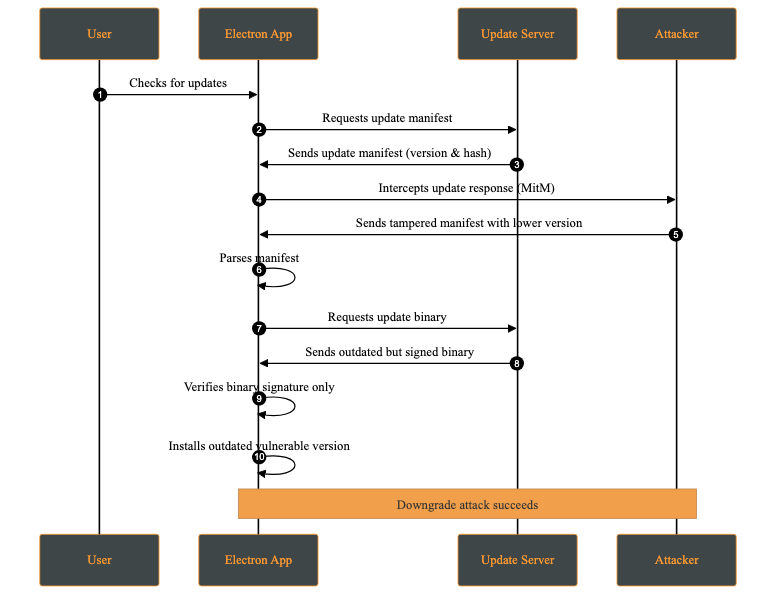

A downgrade attack occurs when an attacker forces the application to install an older, vulnerable version instead of the latest secure release. This may happen by compromising the update server, or intercepting via a MITM (Man-in-The-Middle) attack and modifying the update manifest to offer a lower version.

The attacker’s objective is to reintroduce previously fixed vulnerabilities by deploying an outdated version of the application. Once installed, the attacker can exploit these known weaknesses.

Attack Steps:

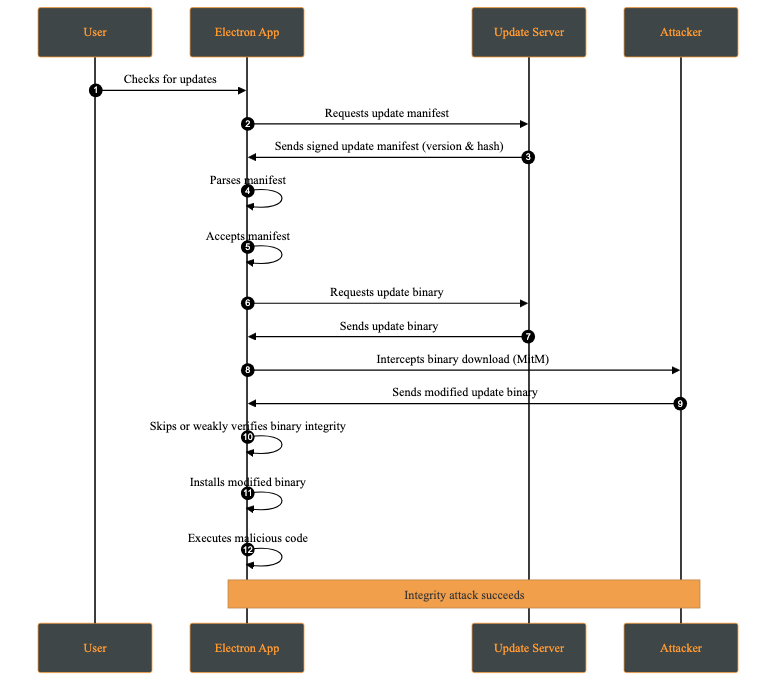

An integrity attack involves the unauthorized modification of update artifacts, such as binaries, installation packages, or metadata, either at rest or during transmission. The attacker’s goal is to have the system execute altered code while believing it originates from a trusted source.

Attack Steps:

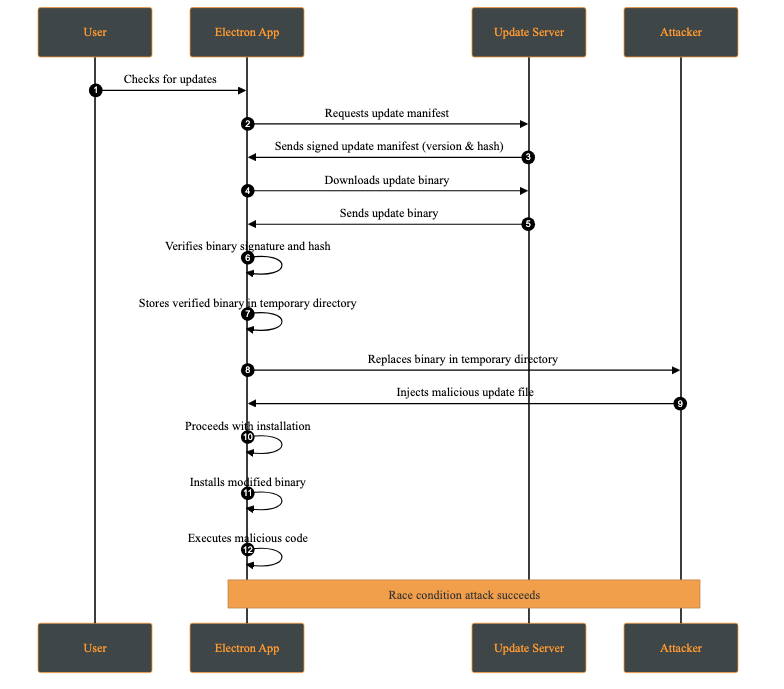

A race condition attack occurs when multiple processes access and modify shared resources concurrently, and the final outcome depends on the timing of those operations. In the context of software updates, this may allow an attacker with local access to replace or modify update files between verification and installation.

This attack requires the attacker to have access to the victim’s machine. While this may appear unlikely, multi-user systems or shared environments make this a realistic threat.

A practical case occurs when the attacker has access to the temporary directory where the update files are stored. This attack is possible whenever signature verification and update application are not performed atomically on the same file descriptor.

Attack Steps:

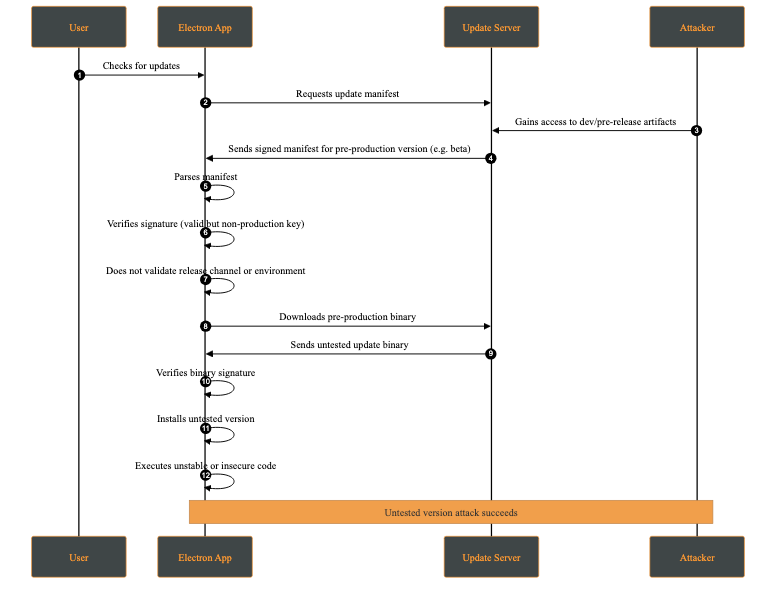

An untested version attack occurs when an attacker causes the client to install a development, pre-production, or experimental version of the application (e.g., alpha or beta) instead of a stable production release. This typically occurs when development and production releases are not cryptographically separated, for example when the same signing keys or update channels are shared across environments.

Although such versions may be signed, they often contain unreviewed features, experimental dependencies, or debug functionality that introduces new vulnerabilities.

Attack Steps:

This behavior makes the client fail to distinguish between production and non-production releases at a cryptographic or policy level.

Our SafeUpdater is built around a set of core security mechanisms designed to protect the update process against the impact of attacks such as downgrade attacks, integrity violations, man-in-the-middle interference, and local race conditions. Each mechanism addresses a specific set of threats identified in the threat model.

The updater is designed to integrate with Electron Builder for application builds; however, this integration is optional, as the manifest can be generated independently.

All update components are cryptographically signed using Ed25519, a modern elliptic-curve signature known for its strong security guarantees. By verifying signatures using a public key embedded in the application, SafeUpdater ensures that update manifests and binaries are from a trusted source and haven’t been tampered with. Any modification to a signed file makes the signature check fail, causing the update to be rejected.

The deterministic message signing is composed of:

SHA-256(file) + version

This prevents unauthorized downgrade attacks by cryptographically binding the update to a specific version identifier.

Once the update asset is received, a signing message is generated. This message will later be used to verify the corresponding signature file:

async function generateMessage(updatePackagePath, version) {

const hash = await _getFileHash(updatePackagePath);

const messageString = `${Buffer.from(hash).toString('hex')}-${version}`;

return Buffer.from(messageString);

}

After generating the message, it is compared against the signature provided alongside the update file. The verification uses the public key associated with the application’s signing infrastructure. If the signature does not match, the update is rejected, preventing malicious modifications from being applied:

export async function verify(publicKeyBuffer, messageBuffer, signatureBuffer) {

return ed.verify(signatureBuffer, messageBuffer, publicKeyBuffer);

}

In addition to signature verification, SafeUpdater checks the SHA-512 hash on the downloaded update binaries. The expected hash is stored in the signed update manifest and compared against the hash of the downloaded file. This layered approach ensures end-to-end integrity, protects against accidental corruption as well as intentional binary tampering during transmission or storage.

// Verify file integrity

const computedHash = createHash('sha512').update(fileContents).digest('base64');

if (computedHash !== expectedSHA512) {

throw new Error('Integrity check failed');

}

Update metadata is distributed through an immutable version manifest that describes available releases, including version numbers, file locations, and cryptographic hashes. Since these manifests are signed, this prevents manifest tampering if the attacker is trying to reintroduce vulnerable versions or pointing them to a malicious location.

To mitigate local attacks such as race conditions (TOCTOU vulnerabilities), SafeUpdater stores temporary update files in restricted directories with owner-only permissions. Verification and installation operate on the same file path, which limits opportunities for tampering. However, these steps are not fully atomic (for example, they do not verify and install using the same file descriptor), so complete elimination of time-of-check to time-of-use risks is not guaranteed.

SafeUpdater ensures secure and reliable updates for Electron applications. This update lifecycle follows a structured process from version check to installation:

${sha256Hex}-${version}SafeUpdater is highly configurable through environment-based JSON files using the config package.

The primary configuration file config/default.json includes the following settings:

The Ed25519 public key used to verify update signatures. This key must be hex-encoded (64 hex characters).

{

"updatesPublicKey": "<..>"

}

Note: You can generate the key using the

generateKeys.jsscript from thetoolsfolder:

node tools/generateKeys.js # Outputs public.key

cat public.key

The base URL for your update server. SafeUpdater constructs paths for manifests and binaries automatically:

{

"updatesUrl": "https://updates.yourcompany.com"

}

Path construction examples:

Releases manifest: ${updatesUrl}/releases/versions.json

Version metadata: ${updatesUrl}/releases/${version}/${version}.yml

Update binaries: ${updatesUrl}/releases/${version}/${filename}

A master switch for the update system:

{

"updatesEnabled": true

}

Provide a PEM-encoded X.509 certificate for TLS validation. This is useful for self-signed certificates during development or as part of a certificate pinning strategy in production.

{

"certificateAuthority": "-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----\nMIIDXTCCAkWgAwIBAgIJAKL...\n-----END CERTIFICATE-----"

}

Disables TLS certificate validation.

{

"allowInsecureTLS": true

}

Warning: Never use this in production! Only for development environments with self-signed certificates.

false)Enables the ability to roll back to a previous version of the app.

{

"downgradeEnabled": true

}

Allows cryptographically verified downgrades and enforces a minimum version to prevent unsafe rollbacks.

For debugging purposes only, we have developed a set of tools under the /tools folder, which provides all tools required to generate the Ed25519 key pairs, sign release artifacts, and produce signed manifests.

This repository allows developers to:

By following the two-step process below, SafeUpdater ensures that end users only receive verified, unmodified updates, protecting against downgrade attacks, tampering, or malicious binaries.

Sign release artifacts after building your application using electron-builder. It is crucial to sign every artifact that will be downloaded or trusted by the updater.

# Sign ZIP file

node tools/sign.js /path/to/my-app-2.0.0-mac.zip "2.0.0"

# Sign DMG file

node tools/sign.js /path/to/my-app-2.0.0.dmg "2.0.0"

# Sign YAML metadata

node tools/sign.js /path/to/2.0.0.yml "2.0.0"

For local testing, you can serve updates over HTTPS using a self-signed certificate.

server.py:

from http.server import HTTPServer, SimpleHTTPRequestHandler

import ssl

port = 443

httpd = HTTPServer(('0.0.0.0', port), SimpleHTTPRequestHandler)

httpd.socket = ssl.wrap_socket(

httpd.socket,

keyfile='key.pem',

certfile='server.pem',

server_side=True

)

print(f"Server running on https://0.0.0.0:{port}")

httpd.serve_forever()

This server is intended strictly for development and testing purposes. In production, deploy behind a properly secured, scalable, and monitored infrastructure.

Even when using modern and widely adopted frameworks, software update mechanisms must compensate for several shortcomings introduced by the underlying operating systems themselves. These limitations place a non-trivial burden on application developers, who are often forced to re-implement critical security guarantees that should ideally be enforced at the platform level.

This project set out to analyze the current limitations of software update mechanisms in ElectronJS and to propose a safer alternative to the approaches commonly used today. By providing strong cryptographic guarantees and a well-defined, transparent update flow, our reference implementation (SafeUpdater) aims to reduce the attack surface associated with software updates and to make secure design choices the default rather than an afterthought. In doing so, it allows developers to focus on building application features without compromising on update security.

SafeUpdater was developed as part of my university thesis at the Polytechnic University of Valencia and during my internship at Doyensec. While the project would still require extensive performance evaluation, security auditing, and real-world testing before being considered production-ready, we believe it offers a solid foundation and a practical starting point for building more robust and trustworthy software update mechanisms for ElectroJs-based applications.

In July 2025, we performed a brief audit of Outline - an OSS wiki similar in many ways to Notion. This activity was meant to evaluate the overall posture of the application, and involved two researchers for a total of 60 person-days. In parallel, we thought it would be a valuable firsthand experience to use three AI security platforms to perform an audit on the very same codebase. Given that all issues are now fixed, we believe it would be interesting to provide an overview of our effort and a few interesting findings and considerations.

While this activity was not sufficient to evaluate the entirety of the Outline codebase, we believe we have a good understanding of its quality and resilience. The security posture of the APIs was found to be above industry best practices. Despite our findings, we were pleased to witness a well-thought-out use of security practices and hardening, especially given the numerous functionalities and integrations available.

It is important to note that Doyensec audited only Outline OSS (v0.85.1). On-premise enterprise and cloud functionalities were considered out of scope for this engagement. For instance, multi-tenancy is not supported in the OSS on-prem release, hence authorization testing did not consider cross-tenant privilege escalations. Finally, testing focused on Outline code only, leaving all dependencies out of scope. Ironically, several of the bugs discovered were actually caused by external libraries.

Large Language Models and AI security platforms are evolving at an exceptionally rapid pace. The observations, assessments, and experiences shared in this post reflect our hands-on exposure at a specific point in time and within a particular technical context. As models, tooling, and defensive capabilities continue to mature, some details discussed here may change or become irrelevant.

When performing an in-depth engagement, it is ideal to set up a testing environment with debugging capabilities for both frontend and backend. Outline’s extensive documentation makes this process easy.

We started by setting up a local environment as documented in this guide, and executing the following commands:

echo "127.0.0.1 local.outline.dev" | sudo tee -a /etc/hosts

mkdir files

The following .env file was used for the configuration(non-empty settings only):

NODE_ENV=development

URL=https://local.outline.dev:3000

PORT=3000

SECRET_KEY=09732bbde65d4...989

UTILS_SECRET=af7b3d5a6cc...2f1

DEFAULT_LANGUAGE=en_US

DATABASE_URL=postgres://user:pass@127.0.0.1:5432/outline

REDIS_URL=redis://127.0.0.1:6379

FILE_STORAGE=local

FILE_STORAGE_LOCAL_ROOT_DIR=./files/

FILE_STORAGE_UPLOAD_MAX_SIZE=262144000

FORCE_HTTPS=true

OIDC_CLIENT_ID=web

OIDC_CLIENT_SECRET=secret

OIDC_AUTH_URI=http://127.0.0.1:9998/auth

OIDC_TOKEN_URI=http://127.0.0.1:9998/oauth/token

OIDC_USERINFO_URI=http://127.0.0.1:9998/userinfo

OIDC_DISABLE_REDIRECT=true

OIDC_USERNAME_CLAIM=preferred_username

OIDC_DISPLAY_NAME=OpenID Connect

OIDC_SCOPES=openid profile email

RATE_LIMITER_ENABLED=true

# ––––––––––––– DEBUGGING ––––––––––––

ENABLE_UPDATES=false

DEBUG=http

LOG_LEVEL=debug

Zitadel’s OIDC server was used for authentication

REDIRECT_URI=https://local.outline.dev:3000/auth/oidc.callback USERS_FILE=./users.json go run github.com/zitadel/oidc/v3/example/server

Finally, VS Code debugging was set up using the following .vscode/launch.json

{

"version": "0.2.0",

"configurations": [

{

"type": "node",

"request": "attach",

"name": "Attach to Outline Backend",

"address": "localhost",

"port": 9229,

"restart": true,

"protocol": "inspector",

"skipFiles": ["<node_internals>/**"],

"cwd": "${workspaceFolder}"

}

]

}

We also facilitated front-end debugging by adding the following setting at the top of the .babelrc file in order to have source maps.

"sourceMaps": true

Doyensec researchers discovered and reported seven (7) unique vulnerabilities affecting Outline OSS.

| ID | Title | Class | Severity | Discoverer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OUT-Q325-01 | Multiple Blind SSRF | SSRF | Medium | 🤖🙍♂️ |

| OUT-Q325-02 | Vite Path Traversal | Injection Flaws | Low | 🙍♂️ |

| OUT-Q325-03 | CSRF via Sibling Domains | CSRF | Medium | 🙍♂️ |

| OUT-Q325-04 | Local File Storage CSP Bypass | Insecure Design | Low | 🙍♂️ |

| OUT-Q325-05 | Insecure Comparison in VerificationCode | Insufficient Cryptography | Low | 🤖🙍♂️ |

| OUT-Q325-06 | ContentType Bypass | Insecure Design | Medium | 🙍♂️ |

| OUT-Q325-07 | Event Access | IDOR | Low | 🤖 |

Among the bugs we discovered, there are a few that require special mention:

OUT-Q325-01 (GHSA-jfhx-7phw-9gq3) is a standard Server-Side Request Forgery bug allowing redirects, but having limited protocols support. Interestingly, this issue affects the self-hosted version only as the cloud release is protected using request-filtering-agent. While giving a quick look at this dependency, we realized that versions 1.x.x and earlier contained a vulnerability (GHSA-pw25-c82r-75mm) where HTTPS requests to 127.0.0.1 bypass IP address filtering, while HTTP requests are correctly blocked. While newer versions of the library were already out, Outline was still using an old release, since no GitHub (or other) advisories were ever created for this issue. Whether intentionally or accidentally, this issue was silently fixed for many years.

OUT-Q325-02 (GHSA-pp7p-q8fx-2968) turned out to be a bug in the vite-plugin-static-copy npm module. Luckily, it only affects Outline in development mode.

OUT-Q325-04 (GHSA-gcj7-c9jv-fhgf) was already exploited in this type confusion attack. In fact, browsers like Chrome and Firefox do not block script execution even if the script is served with Content-Disposition: attachment as long as the content type is a valid application/javascript. Please note that this issue does not affect the cloud-hosted version given it’s not using the local file storage engine altogether.

Investigating this issue led to the discovery of OUT-Q325-06, an even more interesting issue.

Outline allows inline content for specific (safe) types of files as defined in server/storage/files/BaseStorage.ts

/**

* Returns the content disposition for a given content type.

*

* @param contentType The content type

* @returns The content disposition

*/

public getContentDisposition(contentType?: string) {

if (!contentType) {

return "attachment";

}

if (

FileHelper.isAudio(contentType) ||

FileHelper.isVideo(contentType) ||

this.safeInlineContentTypes.includes(contentType)

) {

return "inline";

}

return "attachment";

}

Despite this logic, the actual content type of the response was getting overridden. All Outline versions before v0.84.0 (May 2025) were actually vulnerable to Cross-Site Scripting because of this issue, and it was accidentally mitigated by adding the following CSP directive:

ctx.set("Content-Security-Policy","sandbox");

When analyzing the root cause, it turned out to be an undocumented insecure behavior of KoaJS.

In Outline, the issue was caused by forcing the expected “Content-Type” before the use of response.attachment([filename], [options]) .

ctx.set("Content-Type", contentType);

ctx.attachment(fileName, {

type: forceDownload

? "attachment"

: FileStorage.getContentDisposition(contentType), // this applies the safe allowed-list

});

In fact, the attachment function performs an unexpected:

set type (type) {

type = getType(type)

if (type) {

this.set('Content-Type', type)

} else {

this.remove('Content-Type')

}

},

This insecure behavior is neither documented nor warned against by the framework. Inverting ctx.set and ctx.attachment is sufficient to fix the issue.

Combining OUT-Q325-03, OUT-Q325-06 and Outline’s sharing capabilities, it is possible to take over an admin account, as shown in the following video, affecting the latest version of Outline at the time of testing:

Finally, OUT-Q325-07 (GHSA-h9mv-vg9r-8c7c) was discovered autonomously by a security AI platform. The events.list API endpoint contains an IDOR vulnerability allowing users to view events for any actor or document within their team without proper authorization.

router.post(

"events.list",

auth(),

pagination(),

validate(T.EventsListSchema),

async (ctx: APIContext<T.EventsListReq>) => {

const { user } = ctx.state.auth;

const {

name,

events,

auditLog,

actorId,

documentId,

collectionId,

sort,

direction,

} = ctx.input.body;

let where: WhereOptions<Event> = {

teamId: user.teamId,

};

if (auditLog) {

authorize(user, "audit", user.team);

where.name = events

? intersection(EventHelper.AUDIT_EVENTS, events)

: EventHelper.AUDIT_EVENTS;

} else {

where.name = events

? intersection(EventHelper.ACTIVITY_EVENTS, events)

: EventHelper.ACTIVITY_EVENTS;

}

if (name && (where.name as string[]).includes(name)) {

where.name = name;

}

if (actorId) {

where = { ...where, actorId };

}

if (documentId) {

where = { ...where, documentId };

}

if (collectionId) {

where = { ...where, collectionId };

const collection = await Collection.findByPk(collectionId, {

userId: user.id,

});

authorize(user, "read", collection);

} else {

const collectionIds = await user.collectionIds({

paranoid: false,

});

where = {

...where,

[Op.or]: [

{

collectionId: collectionIds,

},

{

collectionId: {

[Op.is]: null,

},

},

],

};

}

const loadedEvents = await Event.findAll({

where,

order: [[sort, direction]],

include: [

{

model: User,

as: "actor",

paranoid: false,

},

],

offset: ctx.state.pagination.offset,

limit: ctx.state.pagination.limit,

});

ctx.body = {

pagination: ctx.state.pagination,

data: await Promise.all(

loadedEvents.map((event) => presentEvent(event, auditLog))

),

};

}

);

While the code implements team-level isolation (via the teamId check) and collection-level authorization, it fails to validate access to individual events. An attacker can manipulate the actorId or documentId parameters to view events they shouldn’t have access to. This is particularly concerning since audit log events might contain sensitive information (e.g., document titles). This is a nice catch, something that is not immediately evident to a human auditor without an extended understanding of Outline’s authorization model.

Despite the discovery of OUT-Q325-07, our experience using three AI security platforms was, overall, rather disappointing. LLM-based models can identify some vulnerabilities; however, the rate of false positives vastly outweighed the few true positives. What made this especially problematic was how convincing the findings were: the descriptions of the alleged issues were often extremely accurate and well-articulated, making it surprisingly hard to confidently dismiss them as false positives. As a result, cleaning up and validating all AI-reported issues turned into a 40-hour effort.

Such overhead during a paid manual audit is hard to justify for us and, more importantly, for our clients. AI hallucinations repeatedly sent us down unexpected rabbit holes, at times making seasoned consultants, with decades of combined experience, feel like complete newbies. While attempting to validate alleged bugs reported by AI, we found ourselves second-guessing our own judgment, losing valuable time that could have been spent on higher-impact tasks.

While the future undoubtedly involves LLMs, it is not quite here yet for high-quality security engagements targeting popular, well-audited software. At Doyensec, we will continue to explore and experiment with AI-assisted tooling, adopting it when and where it actually adds value. We don’t want to be remembered as anti-AI hypers but we’re equally not interested in outsourcing our expertise to confident-sounding hallucinations. For now, human intuition, experience, and skepticism - combined with top-notch tooling - remain very hard to beat. Challenge us!

OkHttp is the defacto standard HTTP client library for the Android ecosystem. It is therefore crucial for a security analyst to be able to dynamically eavesdrop the traffic generated by this library during testing. While it might seem easy, this task is far from trivial. Every request goes through a series of mutations between the initial request creation and the moment it is transmitted. Therefore, a single injection point might not be enough to get a full picture. One needs a different injection point to find out what is actually going through the wire, while another might be required to understand the initial payload being sent.

In this tutorial we will demonstrate the architecture and the most interesting injection points that can be used to eavesdrop and modify OkHttp requests.

For the purpose of demonstration, I built a simple APK with a flow similar to the app I recently tested. It first creates a Request with a JSON payload. Then, a couple of interceptors perform the following operations:

Looking at this flow it becomes obvious how reversing the actual application protocol isn’t straightforward. Intercepting requests at the moment of actual sending will yield the actual payload being sent over the wire, however it will obscure the JSON payload. Intercepting the request creation, on the other hand, will reveal the actual JSON, but will not reveal custom HTTP headers, authentication token, nor will it allow replaying the request.

In the following examples, I’ll demonstrate two approaches that can be mixed and matched for a full picture. Firstly, I will hook the realCall function and dump the Request from there. Then, I will demonstrate how to follow the consecutive Request mutations done by the Interceptors. However, in real life scenarios hooking every Interceptor implementation might be impractical, especially in obfuscated applications. Instead, I’ll demonstrate how to observe intercept results from an internal RealInterceptorChain.proceed function.

To reliably print the contents of the requests, one needs to prepare the helper functions first. Assuming we have an okhttp3.Request object available, we can use Frida to dump its contents:

function dumpRequest(req, function_name) {

try {

console.log("\n=== " + function_name + " ===");

console.log("method: " + req.method());

console.log("url: " + req.url().toString());

console.log("-- headers --");

dumpHeaders(req);

dumpBody(req);

console.log("=== END ===\n");

} catch (e) {

console.log("dumpRequest failed: " + e);

}

}

Dumping headers requires iterating through the Header collection:

function dumpHeaders(req) {

const headers = req.headers();

try {

if (!headers) return;

const n = headers.size();

for (let i = 0; i < n; i++) {

console.log(headers.name(i) + ": " + headers.value(i));

}

} catch (e) {

console.log("dumpHeaders failed: " + e);

}

}

Dumping the body is the hardest task, as there might be many different RequestBody implementations. However, in practice the following should usually work:

function dumpBody(req) {

const body = req.body();

if (body) {

const ct = body.contentType();

console.log("-- body meta --");

console.log("contentType: " + (ct ? ct.toString() : "(null)"));

try {

console.log("contentLength: " + body.contentLength());

} catch (_) {

console.log("contentLength: (unknown)");

}

const utf8 = readBodyToUtf8(body);

if (utf8 !== null) {

console.log("-- body (utf8) --");

console.log(utf8);

} else {

console.log("-- body -- (not readable: streaming/one-shot/duplex or custom)");

}

} else {

console.log("-- no body --");

}

}

The code above uses another helper function to read the actual bytes from the body and decode it as UTF-8. It does it by utilizng the okio.Buffer function:

function readBodyToUtf8(reqBody) {

try {

if (!reqBody) return null;

const Buffer = Java.use("okio.Buffer");

const buf = Buffer.$new();

reqBody.writeTo(buf);

const out = buf.readUtf8();

return out;

} catch (e) {

return null;

}

}

Now that we have code capable of dumping the request as text, we need to find a reliable way to catch the requests. When attempting to view an outgoing communication, the first instinct is to try and inject the function called to send the request. In the world of OkHttp, the functions closest to this are RealCall.execute() and RealCall.enqueue():

Java.perform (function() {

try {

const execOv = RealCall.execute.overload().implementation = function () {

dumpRequest(this.request(), "RealCall.execute() about to send");

return execOv.call(this);

};

console.log("[+] Hooked RealCall.execute()");

} catch (e) {

console.log("[-] Failed to hook RealCall.execute(): " + e);

}

try {

const enqOv = RealCall.enqueue.overload("okhttp3.Callback").implementation = function (cb) {

dumpRequest(this.request(), "RealCall.enqueue()");

return enqOv.call(this, cb);

};

console.log("[+] Hooked RealCall.enqueue(Callback)");

} catch (e) {

console.log("[-] Failed to hook RealCall.enqueue(): " + e);

}

});

However, after running these hooks, it becomes clear that this approach is insufficient whenever an application uses interceptors:

frida -U -p $(adb shell pidof com.doyensec.myapplication) -l blogpost/request-body.js

____

/ _ | Frida 17.5.1 - A world-class dynamic instrumentation toolkit

| (_| |

> _ | Commands:

/_/ |_| help -> Displays the help system

. . . . object? -> Display information about 'object'

. . . . exit/quit -> Exit

. . . .

. . . . More info at https://frida.re/docs/home/

. . . .

. . . . Connected to CPH2691 (id=8c5ca5b0)

Attaching...

[+] Using OkHttp3.internal.connection.RealCall

[+] Hooked RealCall.execute()

[+] Hooked RealCall.enqueue(Callback)

[*] Non-obfuscated RealCall hooks installed.

[CPH2691::PID::9358 ]->

=== RealCall.enqueue() about to send ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768598890661

}

=== END ===

As can be observed, this approach was useful to disclose the address and the JSON payload. However, the request is far from complete. The custom and authentication headers are missing, and the analyst cannot observe that the payload is later encrypted, making it impossible to infer the full application protocol. Therefore, we need to find a more comprehensive method.

Since the modifications are performed inside the OkHttp Interceptors, our next injection target will be the okhttp3.internal.http.RealInterceptorChain class. Given that this is an internal function, it’s bound to be less stable than regular OkHttp classes. Therefore, instead of hooking a function with a single signature, we’ll iterate all overloads of RealInterceptorChain.proceed:

const Chain = Java.use("okhttp3.internal.http.RealInterceptorChain");

console.log("[+] Found okhttp3.internal.http.RealInterceptorChain");

if (Chain.proceed) {

const ovs = Chain.proceed.overloads;

for (let i = 0; i < ovs.length; i++) {

const proceed_overload = ovs[i];

console.log("[*] Hooking RealInterceptorChain.proceed overload: " + proceed_overload.argumentTypes.map(t => t.className).join(", "));

proceed_overload.implementation = function () {

// implementation override here

};

}

console.log("[+] Hooked RealInterceptorChain.proceed(*)");

} else {

console.log("[-] RealInterceptorChain.proceed not found (unexpected)");

}

To understand the code inside the implementation, we need to understand how the proceed functions work. The RealInterceptorChain function maintains the entire chain. When proceed is called by the library (or previous Interceptor) the this.index value is incremented and the next Interceptor is taken from the collection and applied to the Request. Therefore, at the moment of the proceed call, we have a state of Request that is the result of a previous Interceptor call. So, in order to properly assign Request states to proper Interceptors, we’ll need to take a name of an Interceptor number index - 1:

proceed_overload.implementation = function () {

// First arg is Request in all proceed overloads.

const req = arguments[0];

// Get current index

const idx = this.index.value;

// Get previous interceptor name

// Previous interceptor is the one responsible for the current req state

var interceptorName = "";

if (idx == 0) {

interceptorName = "Original request";

} else {

interceptorName = "Interceptor " + this.interceptors.value.get(idx-1).getClass().getName();

}

dumpRequest(req, interceptorName);

// Call the actual proceed

return proceed_overload.apply(this, arguments);

};

The example result will look similar to the following:

[*] Hooking RealInterceptorChain.proceed overload: OkHttp3.Request

[+] Hooked RealInterceptorChain.proceed(*)

[+] Hooked OkHttp3.Interceptor.intercept(Chain)

[*] RealCall hooks installed.

[CPH2691::PID::19185 ]->

=== RealCall.enqueue() ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768677868986

}

=== END ===

=== Original request ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768677868986

}

=== END ===

=== Interceptor com.doyensec.myapplication.MainActivity$HeaderInterceptor ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

X-PoC: frida-test

X-Device: android

Content-Type: application/json

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768677868986

}

=== END ===

=== Interceptor com.doyensec.myapplication.MainActivity$SignatureInterceptor ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

X-PoC: frida-test

X-Device: android

Content-Type: application/json

X-Signature: 736c014442c5eebe822c1e2ecdb97c5d

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768677868986

}

=== END ===

=== Interceptor com.doyensec.myapplication.MainActivity$EncryptBodyInterceptor ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

X-PoC: frida-test

X-Device: android

Content-Type: application/json

X-Signature: 736c014442c5eebe822c1e2ecdb97c5d

X-Content-Encryption: AES-256-GCM

X-Content-Format: base64(iv+ciphertext+tag)

-- body meta --

contentType: application/octet-stream

contentLength: 120

-- body (utf8) --

YIREhdesuf1VdvxeCO+H/8/N8NYFJ2r5Jk4Im40fjyzVI2rzufpejFOHQ67hkL8UFdniknpABmjoP73F2Z4Vbz3sPAxOp7ZXaz5jWLlk3T6B5sm2QCAjKA==

=== END ===

...

With such output we can easily observe the consecutive mutations of the request: the initial payload, the custom headers being added, the X-Signature being added and finally, the payload encryption. With the proper Interceptor names an analyst also receives strong signals as to which classes to target in order to reverse-engineer these operations.

In this post we walked through a practical approach to dynamically intercept OkHttp traffic using Frida.

We started by instrumenting RealCall.execute() and RealCall.enqueue(), which gives quick visibility into endpoints and plaintext request bodies. While useful, this approach quickly falls short once applications rely on OkHttp interceptors to add authentication headers, calculate signatures, or encrypt payloads.

By moving one level deeper and hooking RealInterceptorChain.proceed(), we were able to observe the request as it evolves through each interceptor in the chain. This allowed us to reconstruct the full application protocol step by step - from the original JSON payload, through header enrichment and signing, then all the way to the final encrypted body sent over the wire.

This technique is especially useful during security assessments, where understanding how a request is built is often more important than simply seeing the final bytes on the network. Mapping concrete request mutations back to specific interceptor classes also provides clear entry points for reverse-engineering custom cryptography, signatures, or authorization logic.

In short, when dealing with modern Android applications, intercepting OkHttp at a single point is rarely sufficient. Combining multiple injection points — and in particular leveraging the interceptor chain — provides the visibility needed to fully understand and manipulate application-level protocols.