ABOUT US

We are security engineers who break bits and tell stories.

Visit us

doyensec.com

Follow us

@doyensec

Engage us

info@doyensec.com

Blog Archive

© 2026 Doyensec LLC

We are releasing an internal tool to speed-up testing and reporting efforts in complex functional flows. We’re excited to announce that PESD Exporter is now available on Github.

Modern web platforms design involves integrations with other applications and cloud services to add functionalities, share data and enrich the user experience. The resulting functional flows are characterized by multiple state-changing steps with complex trust boundaries and responsibility separation among the involved actors.

In such situations, web security specialists have to manually model sequence diagrams if they want to support their analysis with visualizations of the whole functionality logic.

We all know that constructing sequence diagrams by hand is tedious, error-prone, time-consuming and sometimes even impractical (dealing with more than ten messages in a single flow).

Proxy Enriched Sequence Diagrams (PESD) is our internal Burp Suite extension to visualize web traffic in a way that facilitates the analysis and reporting in scenarios with complex functional flows.

A Proxy Enriched Sequence Diagram (PESD) is a specific message syntax for sequence diagram models adapted to bring enriched information about the represented HTTP traffic. The MermaidJS sequence diagram syntax is used to render the final diagram.

While classic sequence diagrams for software engineering are meant for an abstract visualization and all the information is carried by the diagram itself. PESD is designed to include granular information related to the underlying HTTP traffic being represented in the form of metadata.

The Enriched part in the format name originates from the diagram-metadata linkability. In fact, the HTTP events in the diagram are marked with flags that can be used to access the specific information from the metadata.

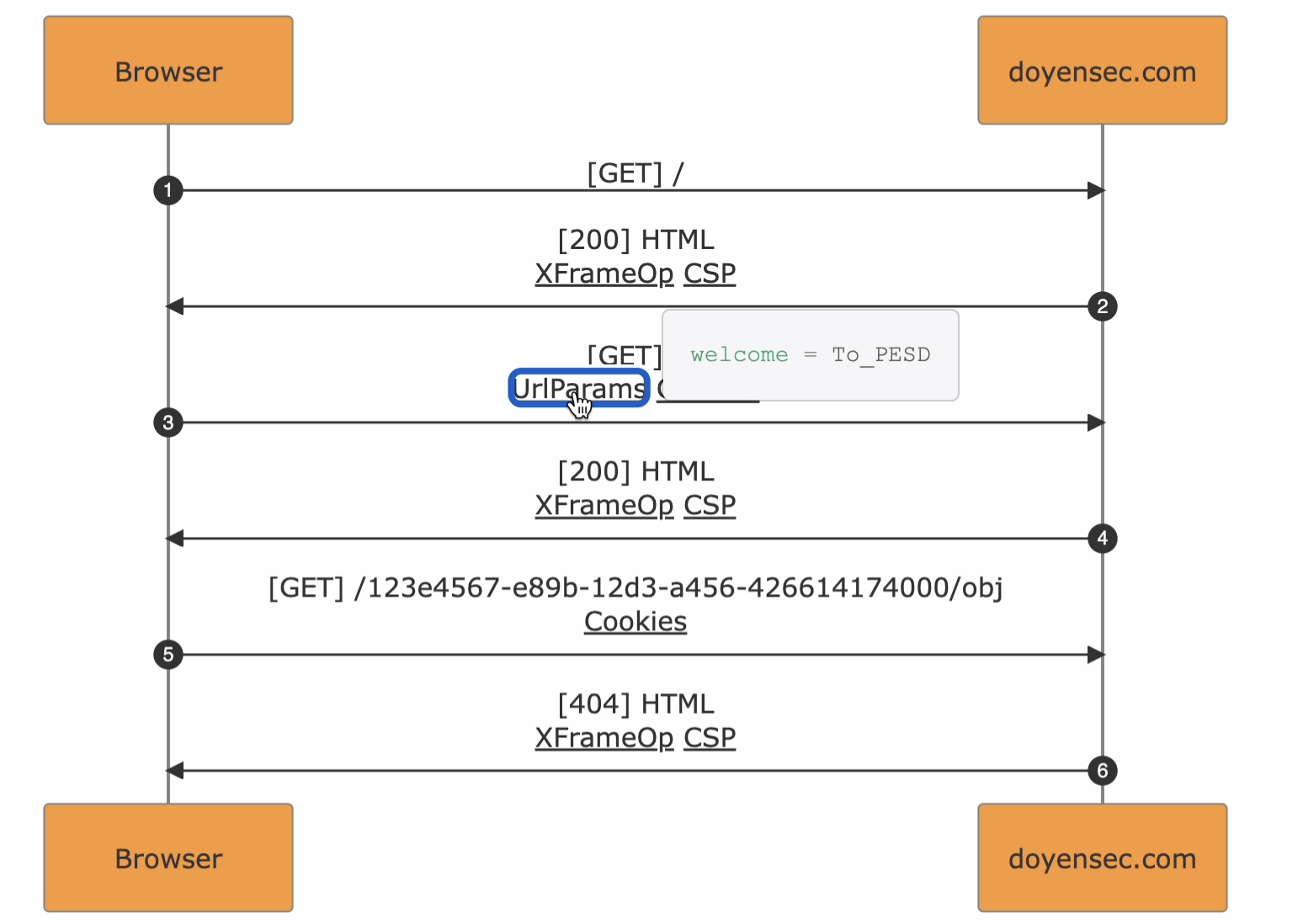

As an example, URL query parameters will be found in the arrow events as UrlParams expandable with a click.

Some key characteristics of the format :

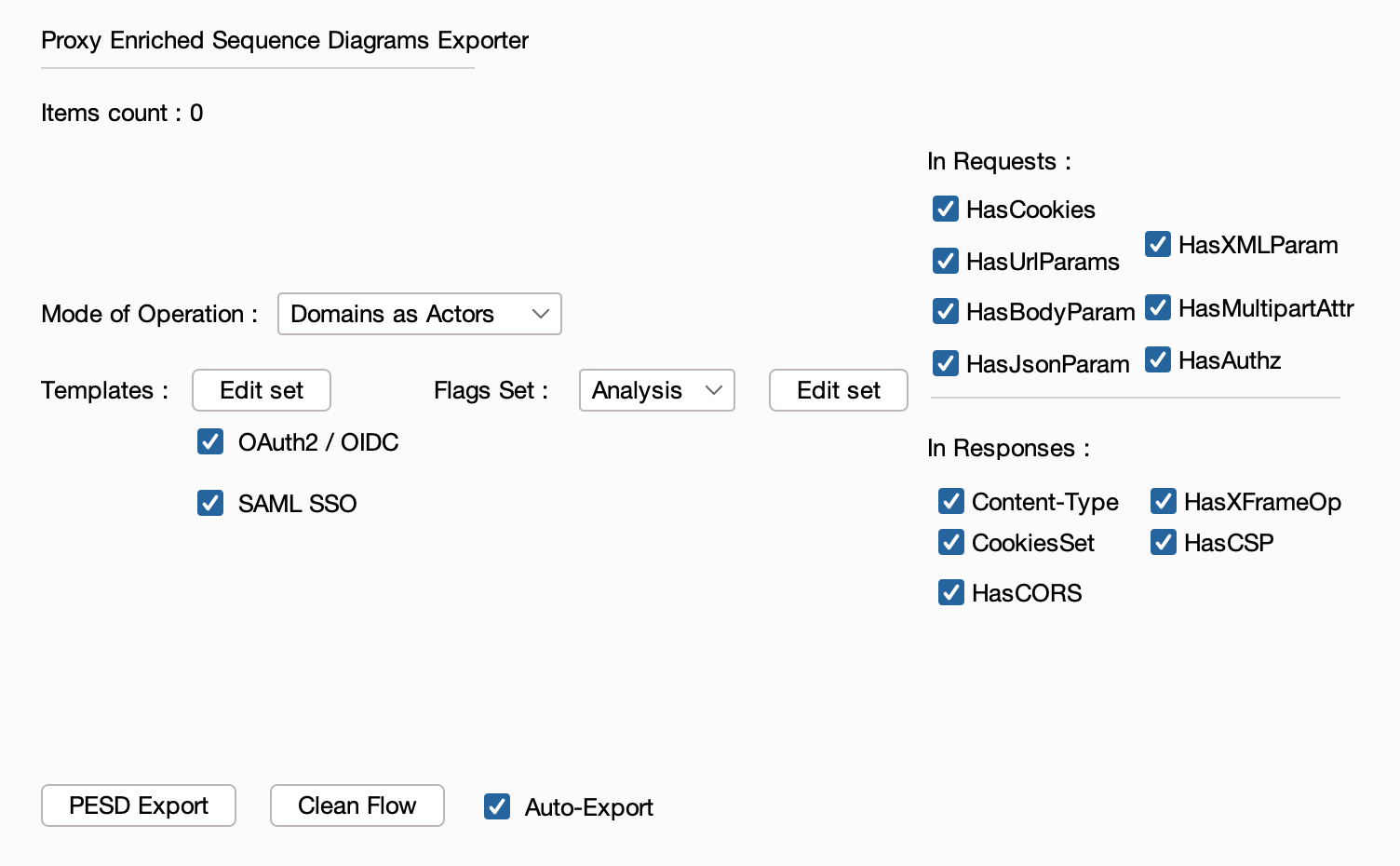

The extension handles Burp Suite traffic conversion to the PESD format and offers the possibility of executing templates that will enrich the resulting exports.

Once loaded, sending items to the extension will directly result in a export with all the active settings.

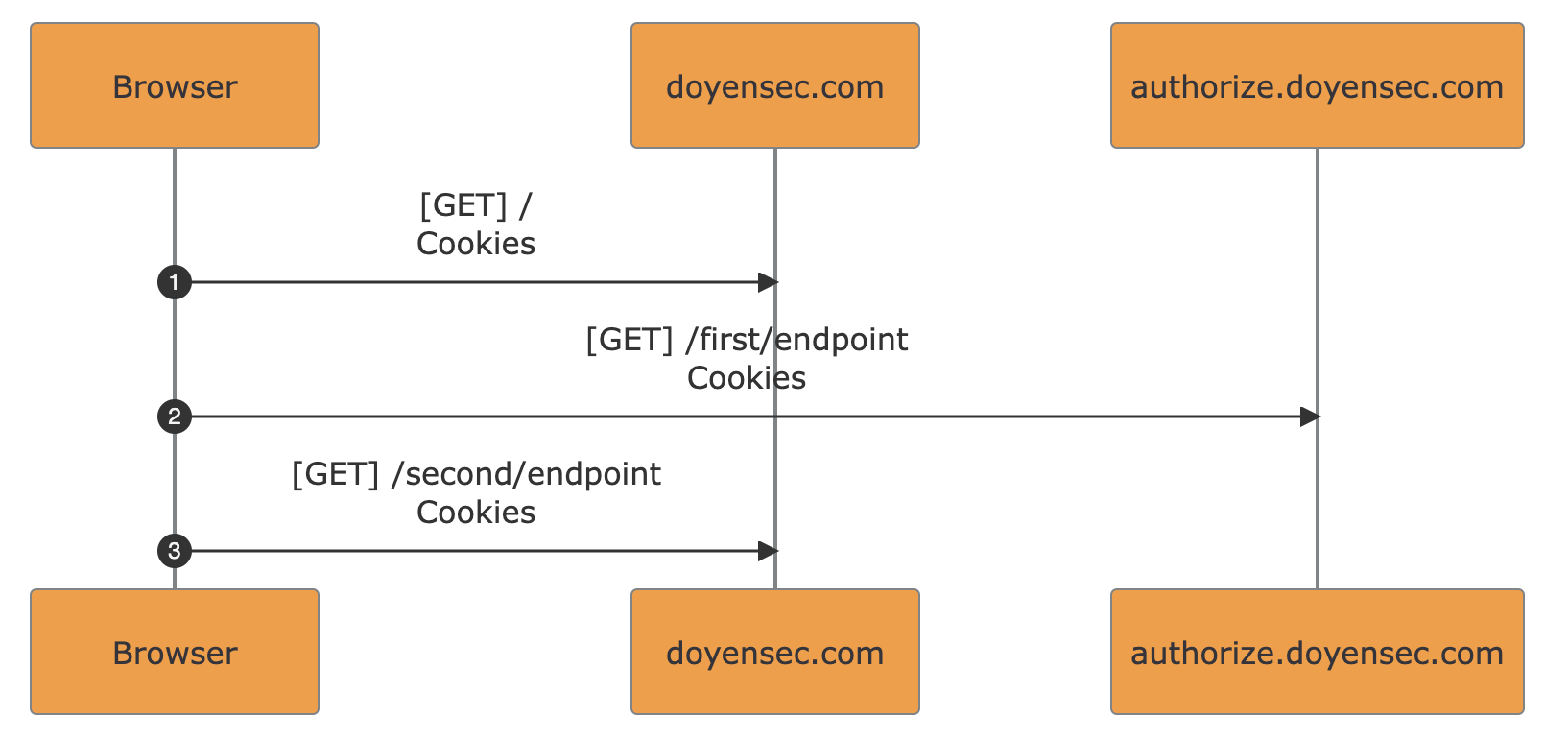

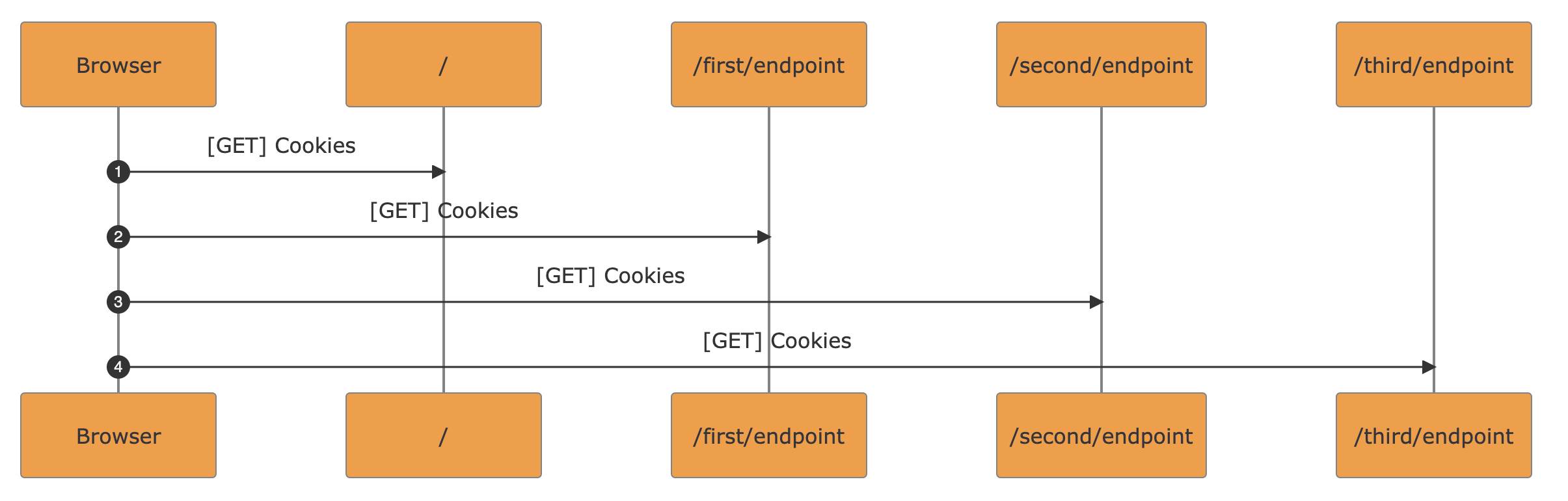

Currently, two modes of operation are supported:

multi-domain flows analysis

single-domain flows analysis

Expandable Metadata. Underlined flags can be clicked to show the underlying metadata from the traffic in a scrollable popover

Masked Randoms in URL Paths. UUIDs and pseudorandom strings recognized inside path segments are mapped to variable names <UUID_N> / <VAR_N>. The re-renderization will reshape the diagram to improve flow readability. Every occurrence with the same value maintains the same name

Notes. Comments from Burp Suite are converted to notes in the resulting diagram. Use <br> in Burp Suite comments to obtain multi-line notes in PESD exports

Save as :

SVG formatMarkdown file (MermaidJS syntax),metadata in JSON format. Read about the metadata structure in the format definition page, “exports section”PESD Exporter supports syntax and metadata extension via templates execution. Currently supported templates are:

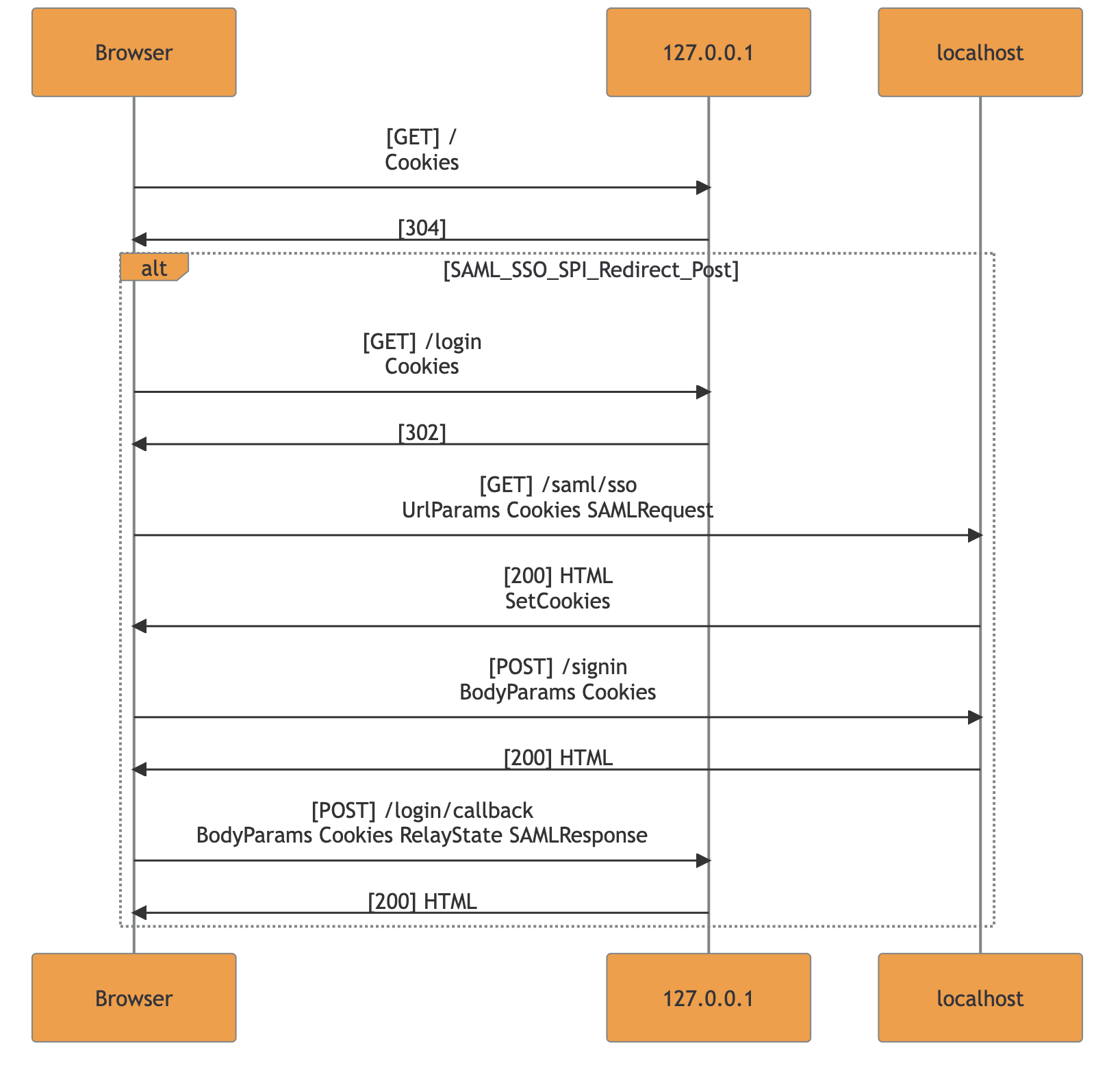

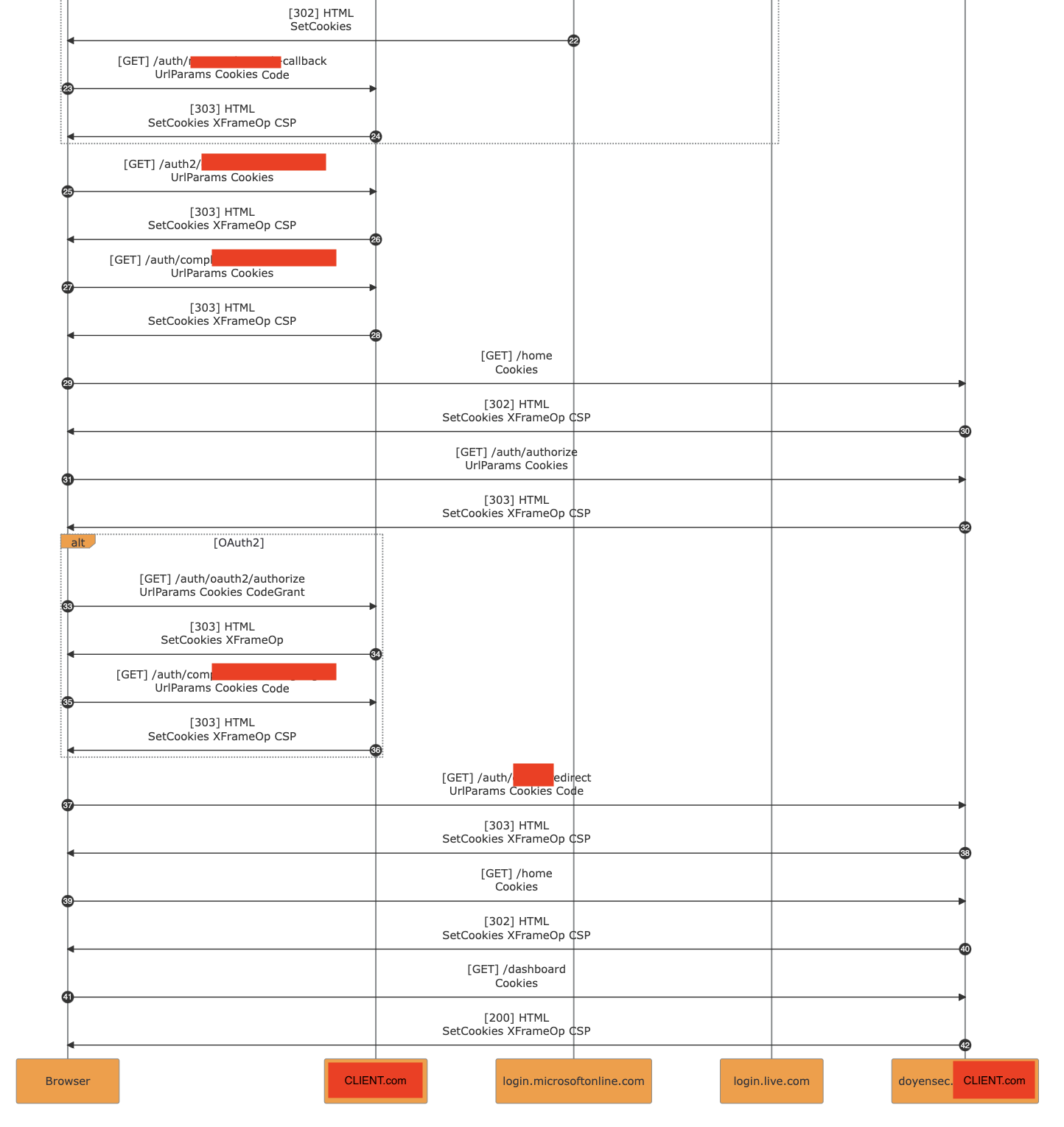

OAuth2 / OpenID Connect The template matches standard OAuth2/OpenID Connect flows and adds related flags + flow frame

SAML SSO The template matches Single-Sign-On flows with SAML V2.0 and adds related flags + flow frame

Template matching example for SAML SP-initiated SSO with redirect POST:

The template engine is also ensuring consistency in the case of crossing flows and bad implementations. The current check prevents nested flow-frames since they cannot be found in real-case scenarios. Nested or unclosed frames inside the resulting markdown are deleted and merged to allow MermaidJS renderization.

Note: Whenever the flow-frame is not displayed during an export involving the supported frameworks, a manual review is highly recommended. This behavior should be considered as a warning that the application is using a non-standard implementation.

Do you want to contribute by writing you own templates? Follow the template implementation guide.

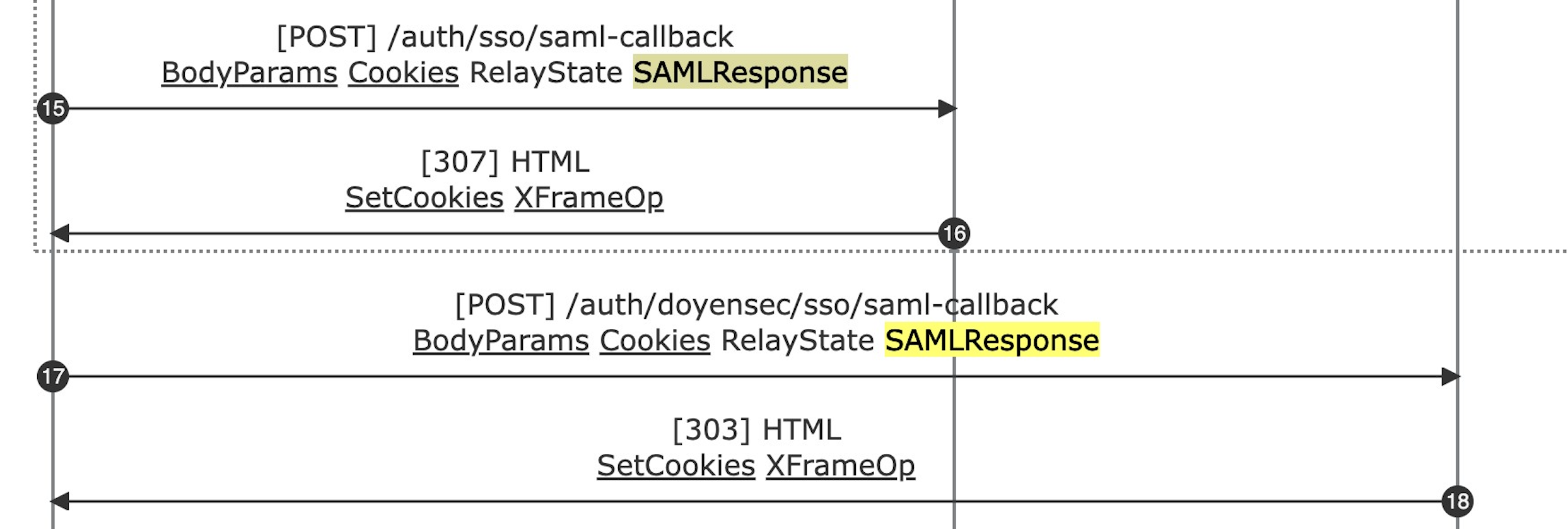

PESD exports allow visualizing the entirety of complex functionalities while still being able to access the core parts of its underlying logic. The role of each actor can be easily derived and used to build a test plan before diving in Burp Suite.

It can also be used to spot the differences with standard frameworks thanks to the HTTP messages syntax along with OAuth2/OpenID and SAML SSO templates.

In particular, templates enable the tester to identify uncommon implementations by matching standard flows in the resulting diagram. By doing so, custom variations can be spotted with a glance.

The following detailed examples are extracted from our testing activities:

The major benefit from the research output was the conjunction of the diagrams generated with PESD with the analysis of the vulnerability. The inclusion of PoC-specific exports in reports allows to describe the issue in a straightforward way.

The export enables the tester to refer to a request in the flow by specifying its ID in the diagram and link it in the description. The vulnerability description can be adapted to different testing approaches:

Black Box Testing - The description can refer to the interested sequence numbers in the flow along with the observed behavior and flaws;

White Box Testing - The description can refer directly to the endpoint’s handling function identified in the codebase. This result is particularly useful to help the reader in linking the code snippets with their position within the entire flow.

In that sense, PESD can positively affect the reporting style for vulnerabilities in complex functional flows.

The following basic example is extracted from one of our client engagements.

An internal (Intranet) Web Application used by the super-admins allowed privileged users within the application to obtain temporary access to customers’ accounts in the web facing platform.

In order to restrict the access to the customers’ data, the support access must be granted by the tenant admin in the web-facing platform. In this way, the admins of the internal application had user access only to organizations via a valid grant.

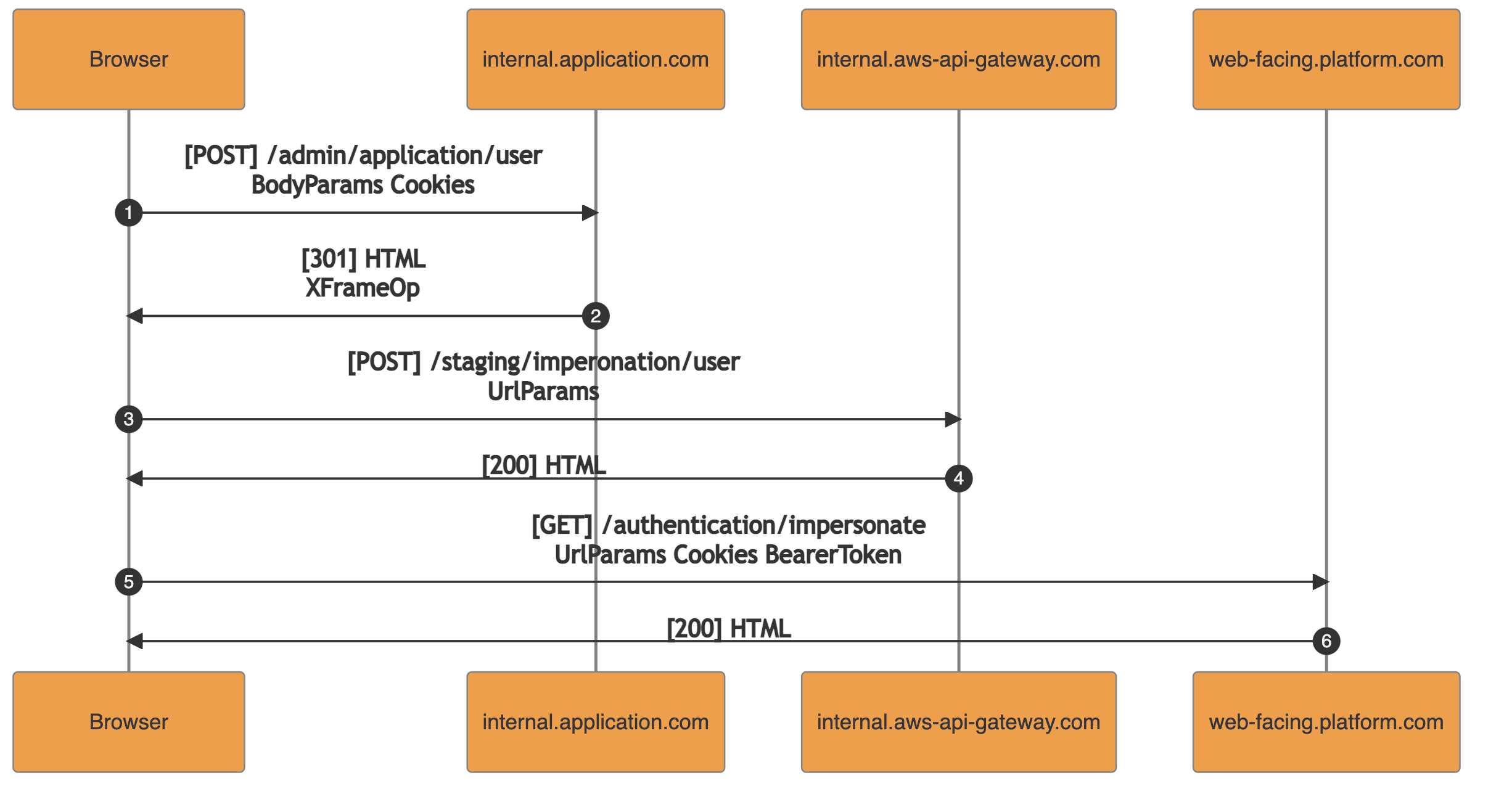

The following sequence diagram represents the traffic intercepted during a user impersonation access in the internal application:

The handling function of the first request (1) checked the presence of an access grant for the requested user’s tenant. If there were valid grants, it returned the redirection URL for an internal API defined in AWS’s API Gateway. The API was exposed only within the internal network accessible via VPN.

The second request (3) pointed to the AWS’s API Gateway. The endpoint was handled with an AWS Lambda function taking as input the URL parameters containing : tenantId, user_id, and others. The returned output contained the authentication details for the requested impersonation session: access_token, refresh_token and user_id. It should be noted that the internal API Gateway endpoint did not enforce authentication and authorization of the caller.

In the third request (5), the authentication details obtained are submitted to the web-facing.platform.com and the session is set. After this step, the internal admin user is authenticated in the web-facing platform as the specified target user.

Within the described flow, the authentication and authorization checks (handling of request 1) were decoupled from the actual creation of the impersonated session (handling of request 3).

As a result, any employee with access to the internal network (VPN) was able to invoke the internal AWS API responsible for issuing impersonated sessions and obtain access to any user in the web facing platform. By doing so, the need of a valid super-admin access to the internal application (authentication) and a specific target-user access grant (authorization) were bypassed.

Updates are coming. We are looking forward to receiving new improvement ideas to enrich PESD even further.

Feel free to contribute with pull requests, bug reports or enhancements.

This project was made with love in the Doyensec Research island by Francesco Lacerenza . The extension was developed during his internship with 50% research time.

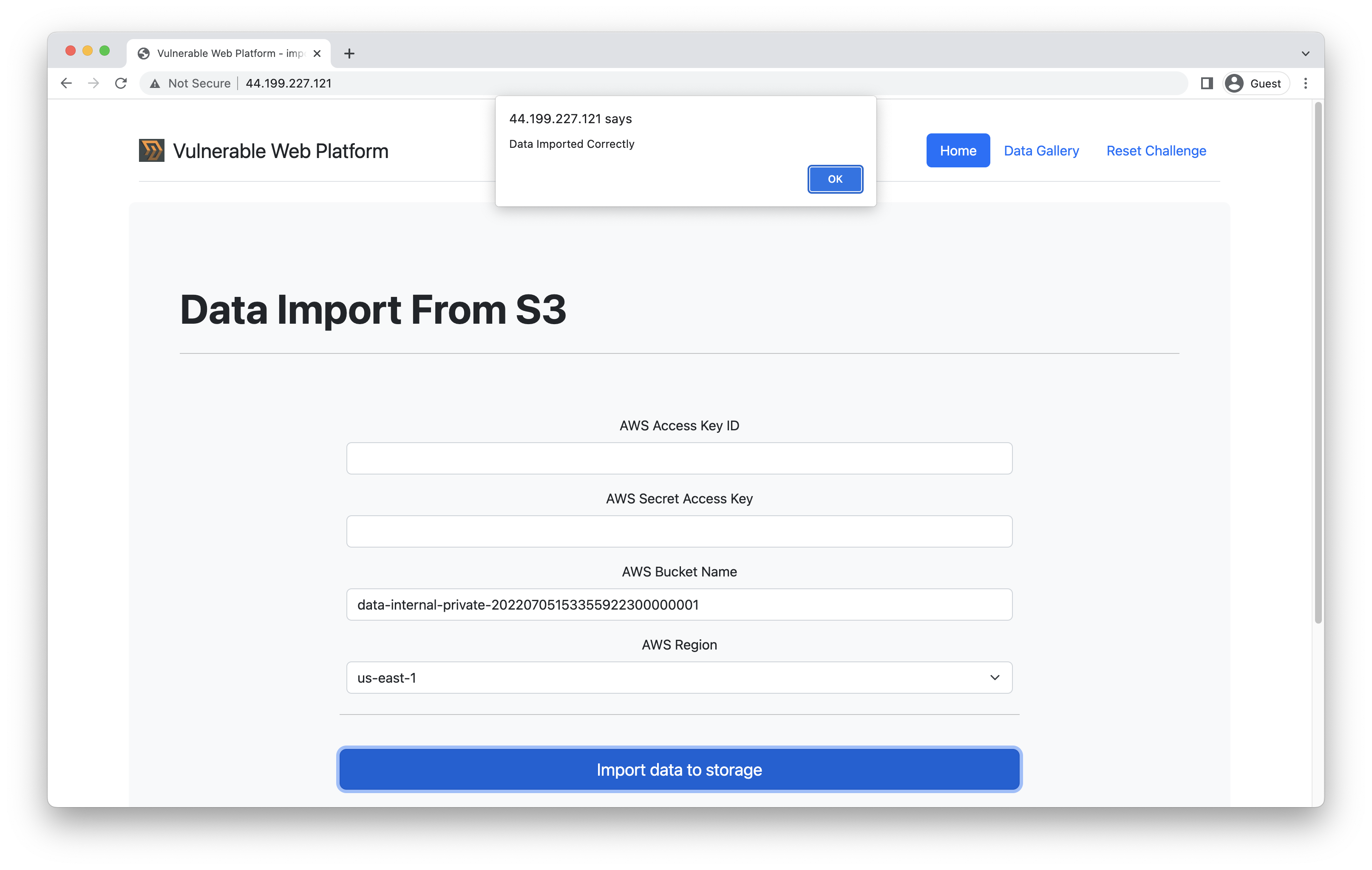

The challenge for the data-import CloudSecTidbit is basically reading the content of an internal bucket. The frontend web application is using the targeted bucket to store the logo of the app.

The name of the bucket is returned to the client by calling the /variable endpoint:

$.ajax({

type: 'GET',

url: '/variable',

dataType: 'json',

success: function (data) {

let source_internal = `https://${data}.s3.amazonaws.com/public-stuff/logo.png?${Math.random()}`;

$(".logo_image").attr("src", source_internal);

},

error: function (jqXHR, status, err) {

alert("Error getting variable name");

}

});

The server will return something like:

"data-internal-private-20220705153355922300000001"

So the schema should be clear now. Let’s use the data import functionality and try to leak the content of the data-internal-private S3 bucket:

Extracting data from the internal S3 bucket

Extracting data from the internal S3 bucketThen, by visiting the Data Gallery section, you will see the keys.txt and dummy.txt objects, which are stored within the internal bucket.

Amazon Web Services offer a complete solution to add user sign-up, sign-in, and access control to web and mobile applications: Cognito. Let’s first talk about the service in general terms.

From AWS Cognito’s welcome page:

“Using the Amazon Cognito user pools API, you can create a user pool to manage directories and users. You can authenticate a user to obtain tokens related to user identity and access policies.”

Amazon Cognito collects a user’s profile attributes into directories called pools that an application uses to handle all authentication related tasks.

The two main components of Amazon Cognito are:

With a user pool, users can sign in to an app through Amazon Cognito, OAuth2, and SAML identity providers.

Each user has a profile that applications can access through the software development kit (SDK).

User attributes are pieces of information stored to characterize individual users, such as name, email address, and phone number. A new user pool has a set of default standard attributes. It is also possible to add custom attributes to satisfy custom needs.

An app is an entity within a user pool that has permission to call management operation APIs, such as those used for user registration, sign-in, and forgotten passwords.

In order to call the operation APIs, an app client ID and an optional client secret are needed. Multiple app integrations can be created for a single user pool, but typically, an app client corresponds to the platform of an app.

A user can be authenticated in different ways using Cognito, but the main options are:

AdminInitiateAuth API operation. This operation requires AWS credentials with permissions that include cognito-idp:AdminInitiateAuth and cognito-idp:AdminRespondToAuthChallenge. The operation returns the required authentication parameters.In both the cases, the end-user should receive the resulting JSON Web Token.

After that first look at AWS SDK credentials, we can jump straight to the tidbit case.

For this case, we will focus on a vulnerability identified in a Web Platform that was using AWS Cognito.

The platform used Cognito to manage users and map them to their account in a third-party platform X_platform strictly interconnected with the provided service.

In particular, users were able to connect their X_platform account and allow the platform to fetch their data in X_platform for later use.

{

"sub": "cf9..[REDACTED]",

"device_key": "us-east-1_ab..[REDACTED]",

"iss": "https://cognito-idp.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/us-east-1_..[REDACTED]",

"client_id": "9..[REDACTED]",

"origin_jti": "ab..[REDACTED]",

"event_id": "d..[REDACTED]",

"token_use": "access",

"scope": "aws.cognito.signin.user.admin",

"auth_time": [REDACTED],

"exp": [REDACTED],

"iat": [REDACTED],

"jti": "3b..[REDACTED]",

"username": "[REDACTED]"

}

In AWS Cognito, user tokens permit calls to all the User Pool APIs that can be hit using access tokens alone.

The permitted API definitions can be found here.

If the request syntax for the API call includes the parameter "AccessToken": "string", then it allows users to modify something on their own UserPool entry with the previously inspected JWT.

The above described design does not represent a vulnerability on its own, but having users able to edit their own User Attributes in the pool could lead to severe impacts if the backend is using them to apply internal platform logic.

The user associated data within the pool was fetched by using the AWS CLI:

$ aws cognito-idp get-user --region us-east-1--access-token eyJra..[REDACTED SESSION JWT]

{

"Username": "[REDACTED]",

"UserAttributes": [

{

"Name": "sub",

"Value": "cf915…[REDACTED]"

},

{

"Name": "email_verified",

"Value": "true"

},

{

"Name": "name",

"Value": "[REDACTED]"

},

{

"Name": "custom:X_platform_user_id",

"Value": "[REDACTED ID]"

},

{

"Name": "email",

"Value": "[REDACTED]"

}

]

}

After finding the X_platform_user_id user pool attribute, it was clear

that it was there for a specific purpose. In fact, the platform was

fetching the attribute to use it as the primary key to query the

associated refresh_token in an internal database.

Attempting to spoof the attribute was as simple as executing:

$ aws --region us-east-1 cognito-idp update-user-attributes --user-attributes "Name=custom:X_platform_user_id,Value=[ANOTHER REDACTED ID]" --access-token eyJra..[REDACTED SESSION JWT]

The attribute edit succeeded and the data from the other user started to flow into the attacker’s account. The platform trusted the attribute as immutable and used it to retrieve a refresh_token needed to fetch and show data from X_platform in the UI.

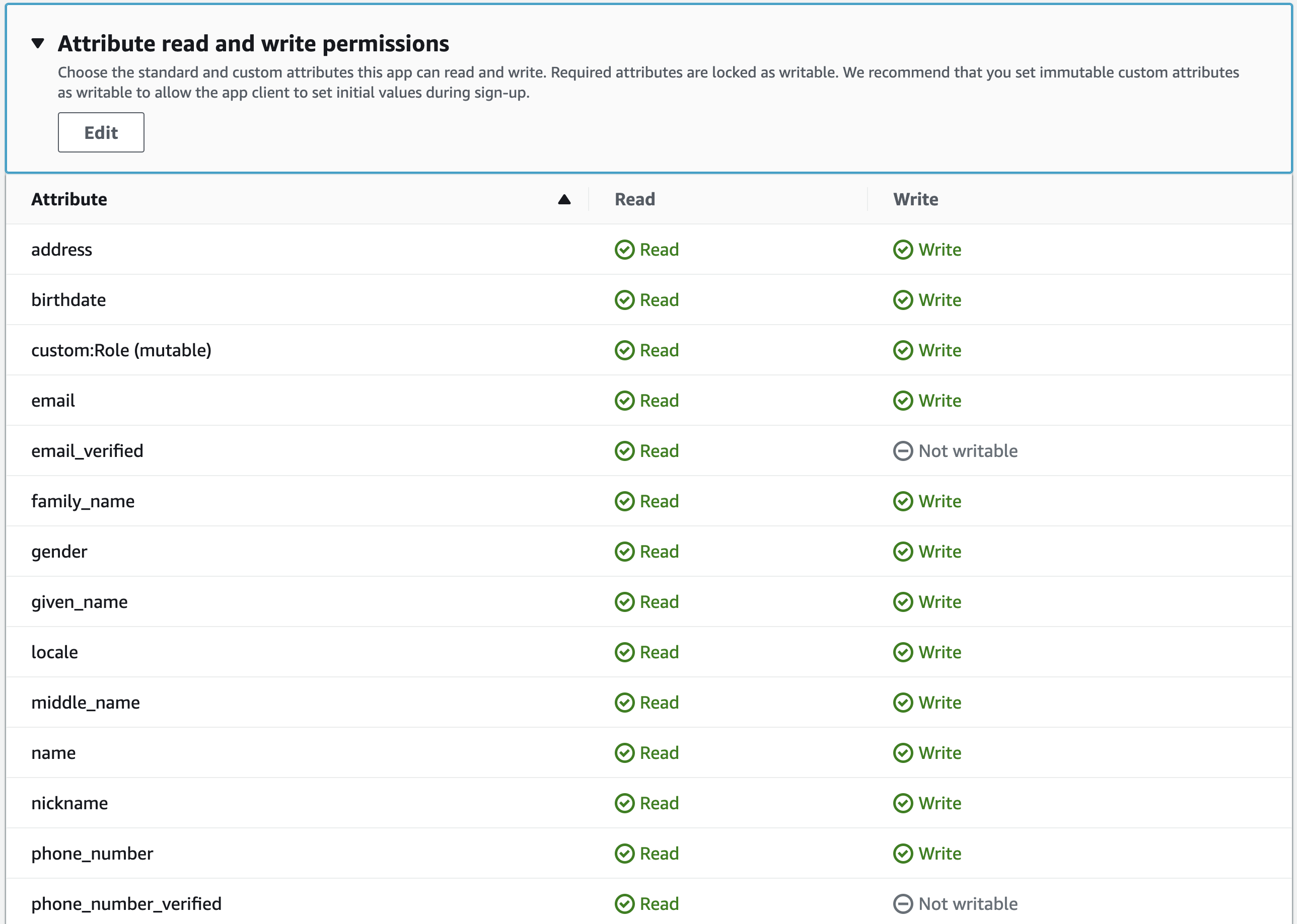

In AWS Cognito, App Integrations (Clients) have default read/write permissions on User Attributes.

The following image shows the “Attribute read and write permissions” configuration for a new App Integration within a User Pool.

Consequently, authenticated users are able to edit their own attributes by using the access token (JWT) and AWS CLI.

In conclusion, it is very important to know about such behavior and set the permissions correctly during the pool creation. Depending on the platform logic, some attributes should be set as read-only to make them trustable by internal flows.

While auditing cloud-driven web platforms, look for JWTs issued by AWS Cognito, then answer the following questions:

Remove write permissions for every platform-critical user attribute within App Integration for the used Users Pool (AWS Cognito).

By removing it, users will not be able to perform attribute updates using their access tokens.

Updates will be possible only via admin actions such as the admin-update-user-attributes method, which requires AWS credentials.

+1 remediation tip: To avoid doing it by hand, apply the r/w config in your IaC and have the infrastructure correctly deployed. Terraform example:

resource "aws_cognito_user_pool" "my_pool" {

name = "my_pool"

}

...

resource "aws_cognito_user_pool" "pool" {

name = "pool"

}

resource "aws_cognito_user_pool_client" "client" {

name = "client"

user_pool_id = aws_cognito_user_pool.pool.id

read_attributes = ["email"]

write_attributes = ["email"]

}

The given Terraform example file will create a pool where the client will have only read/write permissions on the “email” attribute. In fact, if at least one attribute is specified either in the read_attributes or write_attributes lists, the default r/w policy will be ignored.

By doing so, it is possible to strictly specify the attributes with read/write permissions while implicitly denying them on the non-specified ones.

Please ensure to properly handle the email and phone number verification in Cognito context. Since they may contain unverified values, remember to apply the RequireAttributesVerifiedBeforeUpdate parameter.

As promised in the series’ introduction, we developed a Terraform (IaC) laboratory to deploy a vulnerable dummy application and play with the vulnerability: https://github.com/doyensec/cloudsec-tidbits/

Stay tuned for the next episode!

During our audits we occasionally stumble across ImageMagick security policy configuration files (policy.xml), useful for limiting the default behavior and the resources consumed by the library. In the wild, these files often contain a plethora of recommendations cargo cultured from around the internet. This normally happens for two reasons:

With this in mind, we decided to study the effects of all the options accepted by ImageMagick’s security policy parser and write a tool to assist both the developers and the security teams in designing and auditing these files. Because of the number of available options and the need to explicitly deny all insecure settings, this is usually a manual task, which may not identify subtle bypasses which undermine the strength of a policy. It’s also easy to set policies that appear to work, but offer no real security benefit. The tool’s checks are based on our research aimed at helping developers to harden their policies and improve the security of their applications, to make sure policies provide a meaningful security benefit and cannot be subverted by attackers.

The tool can be found at imagemagick-secevaluator.doyensec.com/.

A number of seemingly secure policies can be found online, specifying a list of insecure coders similar to:

...

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="EPHEMERAL" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="EPI" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="EPS" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="MSL" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="MVG" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="PDF" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="PLT" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="PS" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="PS2" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="PS3" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="SHOW" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="TEXT" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="WIN" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="XPS" />

...

In ImageMagick 6.9.7-7, an unlisted change was pushed. The policy parser changed behavior from disallowing the use of a coder if there was at least one none-permission rule in the policy to respecting the last matching rule in the policy for the coder. This means that it is possible to adopt an allowlist approach in modern policies, first denying all coders rights and enabling the vetted ones. A more secure policy would specify:

...

<policy domain="delegate" rights="none" pattern="*" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="*" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="read | write" pattern="{GIF,JPEG,PNG,WEBP}" />

...

Consider the following directive:

...

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="ephemeral,epi,eps,msl,mvg,pdf,plt,ps,ps2,ps3,show,text,win,xps" />

...

With this, conversions will still be allowed, since policy patterns are case sensitive. Coders and modules must always be upper-case in the policy (e.g. “EPS” not “eps”).

Denial of service in ImageMagick is quite easy to achieve. To get a fresh set of payloads it’s convenient to search “oom” or similar keywords in the recently opened issues reported on the Github repository of the library. This is an issue since an ImageMagick instance accepting potentially malicious inputs (which is often the case) will always be prone to be exploited. Because of this, the tool also reports if reasonable limits are not explicitly set by the policy.

Once a policy is defined, it’s important to make sure that the policy file is taking effect. ImageMagick packages bundled with the distribution or installed as dependencies through multiple package managers may specify different policies that interfere with each other. A quick find on your local machine will identify multiple occurrences of policy.xml files:

$ find / -iname policy.xml

# Example output on macOS

/usr/local/etc/ImageMagick-7/policy.xml

/usr/local/Cellar/imagemagick@6/6.9.12-60/etc/ImageMagick-6/policy.xml

/usr/local/Cellar/imagemagick@6/6.9.12-60/share/doc/ImageMagick-6/www/source/policy.xml

/usr/local/Cellar/imagemagick/7.1.0-45/etc/ImageMagick-7/policy.xml

/usr/local/Cellar/imagemagick/7.1.0-45/share/doc/ImageMagick-7/www/source/policy.xml

# Example output on Ubuntu

/usr/local/etc/ImageMagick-7/policy.xml

/usr/local/share/doc/ImageMagick-7/www/source/policy.xml

/opt/ImageMagick-7.0.11-5/config/policy.xml

/opt/ImageMagick-7.0.11-5/www/source/policy.xml

Policies can also be configured using the -limit CLI argument, MagickCore API methods, or with environment variables.

Starting from the most restrictive policy described in the official documentation, we designed a restrictive policy gathering all our observations:

<policymap xmlns="">

<policy domain="resource" name="temporary-path" value="/mnt/magick-conversions-with-restrictive-permissions"/> <!-- the location should only be accessible to the low-privileged user running ImageMagick -->

<policy domain="resource" name="memory" value="256MiB"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="list-length" value="32"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="width" value="8KP"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="height" value="8KP"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="map" value="512MiB"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="area" value="16KP"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="disk" value="1GiB"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="file" value="768"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="thread" value="2"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="time" value="10"/>

<policy domain="module" rights="none" pattern="*" />

<policy domain="delegate" rights="none" pattern="*" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="none" pattern="*" />

<policy domain="coder" rights="write" pattern="{PNG,JPG,JPEG}" /> <!-- your restricted set of acceptable formats, set your rights needs -->

<policy domain="filter" rights="none" pattern="*" />

<policy domain="path" rights="none" pattern="@*"/>

<policy domain="cache" name="memory-map" value="anonymous"/>

<policy domain="cache" name="synchronize" value="true"/>

<!-- <policy domain="cache" name="shared-secret" value="my-secret-passphrase" stealth="True"/> Only needed for distributed pixel cache spanning multiple servers -->

<policy domain="system" name="shred" value="2"/>

<policy domain="system" name="max-memory-request" value="256MiB"/>

<policy domain="resource" name="throttle" value="1"/> <!-- Periodically yield the CPU for at least the time specified in ms -->

<policy xmlns="" domain="system" name="precision" value="6"/>

</policymap>

You can verify that a security policy is active using the identify command:

identify -list policy

Path: ImageMagick/policy.xml

...

You can also play with the above policy using our evaluator tool while developing a tailored one.

Do you need a Go HTTP library to protect your applications from SSRF attacks? If so, try safeurl.

It’s a one-line drop-in replacement for Go’s net/http client.

When building a web application, it is not uncommon to issue HTTP requests to internal microservices or even external third-party services. Whenever a URL is provided by the user, it is important to ensure that Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) vulnerabilities are properly mitigated. As eloquently described in PortSwigger’s Web Security Academy pages, SSRF is a web security vulnerability that allows an attacker to induce the server-side application to make requests to an unintended location.

While libraries mitigating SSRF in numerous programming languages exist, Go didn’t have an easy to use solution. Until now!

safeurl for Go is a library with built-in SSRF and DNS rebinding protection that can easily replace Go’s default net/http client. All the heavy work of parsing, validating and issuing requests is done by the library. The library works out-of-the-box with minimal configuration, while providing developers the customizations and filtering options they might need. Instead of fighting to solve application security problems, developers should be free to focus on delivering quality features to their customers.

This library was inspired by SafeCURL and SafeURL, respectively by Jack Whitton and Include Security. Since no SafeURL for Go existed, Doyensec made it available for the community.

safeurl Offer?With minimal configuration, the library prevents unauthorized requests to internal, private or reserved IP addresses. All HTTP connections are validated against an allowlist and a blocklist. By default, the library blocks all traffic to private or reserved IP addresses, as defined by RFC1918. This behavior can be updated via the safeurl’s client configuration. The library will give precedence to allowed items, be it a hostname, an IP address or a port. In general, allowlisting is the recommended way of building secure systems. In fact, it’s easier (and safer) to explicitly set allowed destinations, as opposed to having to deal with updating a blocklist in today’s ever-expanding threat landscape.

Include the safeurl module in your Go program by simply adding github.com/doyensec/safeurl to your project’s go.mod file.

go get -u github.com/doyensec/safeurl

The safeurl.Client, provided by the library, can be used as a drop-in replacement of Go’s native net/http.Client.

The following code snippet shows a simple Go program that uses the safeurl library:

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/doyensec/safeurl"

)

func main() {

config := safeurl.GetConfigBuilder().

Build()

client := safeurl.Client(config)

resp, err := client.Get("https://example.com")

if err != nil {

fmt.Errorf("request return error: %v", err)

}

// read response body

}

The minimal library configuration looks something like:

config := GetConfigBuilder().Build()

Using this configuration you get:

The safeurl.Config is used to customize the safeurl.Client. The configuration can be used to set the following:

AllowedPorts - list of ports the application can connect to

AllowedSchemes - list of schemas the application can use

AllowedHosts - list of hosts the application is allowed to communicate with

BlockedIPs - list of IP addresses the application is not allowed to connect to

AllowedIPs - list of IP addresses the application is allowed to connect to

AllowedCIDR - list of CIDR range the application is allowed to connect to

BlockedCIDR - list of CIDR range the application is not allowed to connect to

IsIPv6Enabled - specifies whether communication through IPv6 is enabled

AllowSendingCredentials - specifies whether HTTP credentials should be sent

IsDebugLoggingEnabled - enables debug logs

Being a wrapper around Go’s native net/http.Client, the library allows you to configure others standard settings as well, such as HTTP redirects, cookie jar settings and request timeouts. Please refer to the official docs for more information on the suggested configuration for production environments.

To showcase how versatile safeurl.Client is, let us show you a few configuration examples.

It is possible to allow only a single schema:

GetConfigBuilder().

SetAllowedSchemes("http").

Build()

Or configure one or more allowed ports:

// This enables only port 8080. All others are blocked (80, 443 are blocked too)

GetConfigBuilder().

SetAllowedPorts(8080).

Build()

// This enables only port 8080, 443, 80

GetConfigBuilder().

SetAllowedPorts(8080, 80, 443).

Build()

// **Incorrect.** This configuration will allow traffic to the last allowed port (443), and overwrite any that was set before

GetConfigBuilder().

SetAllowedPorts(8080).

SetAllowedPorts(80).

SetAllowedPorts(443).

Build()

This configuration allows traffic to only one host, example.com in this case:

GetConfigBuilder().

SetAllowedHosts("example.com").

Build()

Additionally, you can block specific IPs (IPv4 or IPv6):

GetConfigBuilder().

SetBlockedIPs("1.2.3.4").

Build()

Note that with the previous configuration, the safeurl.Client will block the IP 1.2.3.4 in addition to all IPs belonging to internal, private or reserved networks.

If you wish to allow traffic to an IP address, which the client blocks by default, you can use the following configuration:

GetConfigBuilder().

SetAllowedIPs("10.10.100.101").

Build()

It’s also possible to allow or block full CIDR ranges instead of single IPs:

GetConfigBuilder().

EnableIPv6(true).

SetBlockedIPsCIDR("34.210.62.0/25", "216.239.34.0/25", "2001:4860:4860::8888/32").

Build()

DNS rebinding attacks are possible due to a mismatch in the DNS responses between two (or more) consecutive HTTP requests. This vulnerability is a typical TOCTOU problem. At the time-of-check (TOC), the IP points to an allowed destination. However, at the time-of-use (TOU), it will point to a completely different IP address.

DNS rebinding protection in safeurl is accomplished by performing the allow/block list validations on the actual IP address which will be used to make the HTTP request. This is achieved by utilizing Go’s net/dialer package and the provided Control hook. As stated in the official documentation:

// If Control is not nil, it is called after creating the network

// connection but before actually dialing.

Control func(network, address string, c syscall.RawConn) error

In our safeurl implementation, the IPs validation happens inside the Control hook. The following snippet shows some of the checks being performed. If all of them pass, the HTTP dial occurs. In case a check fails, the HTTP request is dropped.

func buildRunFunc(wc *WrappedClient) func(network, address string, c syscall.RawConn) error {

return func(network, address string, _ syscall.RawConn) error {

// [...]

if wc.config.AllowedIPs == nil && isIPBlocked(ip, wc.config.BlockedIPs) {

wc.log(fmt.Sprintf("ip: %v found in blocklist", ip))

return &AllowedIPError{ip: ip.String()}

}

if !isIPAllowed(ip, wc.config.AllowedIPs) && isIPBlocked(ip, wc.config.BlockedIPs) {

wc.log(fmt.Sprintf("ip: %v not found in allowlist", ip))

return &AllowedIPError{ip: ip.String()}

}

return nil

}

}

safeurl Better (and Safer)We’ve performed extensive testing during the library development. However, we would love to have others pick at our implementation.

“Given enough eyes, all bugs are shallow”. Hopefully.

Connect to http://164.92.85.153/ and attempt to catch the flag hosted on this internal (and unauthorized) URL: http://164.92.85.153/flag

The challenge was shut down on 01/13/2023. You can always run the challenge locally, by using the code snippet below.

This is the source code of the challenge endpoint, with the specific safeurl configuration:

func main() {

cfg := safeurl.GetConfigBuilder().

SetBlockedIPs("164.92.85.153").

SetAllowedPorts(80, 443).

Build()

client := safeurl.Client(cfg)

router := gin.Default()

router.GET("/webhook", func(context *gin.Context) {

urlFromUser := context.Query("url")

if urlFromUser == "" {

errorMessage := "Please provide an url. Example: /webhook?url=your-url.com\n"

context.String(http.StatusBadRequest, errorMessage)

} else {

stringResponseMessage := "The server is checking the url: " + urlFromUser + "\n"

resp, err := client.Get(urlFromUser)

if err != nil {

stringError := fmt.Errorf("request return error: %v", err)

fmt.Print(stringError)

context.String(http.StatusBadRequest, err.Error())

return

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

bodyString, err := io.ReadAll(resp.Body)

if err != nil {

context.String(http.StatusInternalServerError, err.Error())

return

}

fmt.Print("Response from the server: " + stringResponseMessage)

fmt.Print(resp)

context.String(http.StatusOK, string(bodyString))

}

})

router.GET("/flag", func(context *gin.Context) {

ip := context.RemoteIP()

nip := net.ParseIP(ip)

if nip != nil {

if nip.IsLoopback() {

context.String(http.StatusOK, "You found the flag")

} else {

context.String(http.StatusForbidden, "")

}

} else {

context.String(http.StatusInternalServerError, "")

}

})

router.GET("/", func(context *gin.Context) {

indexPage := "<!DOCTYPE html><html lang=\"en\"><head><title>SafeURL - challenge</title></head><body>...</body></html>"

context.Writer.Header().Set("Content-Type", "text/html; charset=UTF-8")

context.String(http.StatusOK, indexPage)

})

router.Run("127.0.0.1:8080")

}

If you are able to bypass the check enforced by the safeurl.Client, the content of the flag will give you further instructions on how to collect your reward. Please note that unintended ways of getting the flag (e.g., not bypassing safeurl.Client) are considered out of scope.

Feel free to contribute with pull requests, bug reports or enhancements ideas.

This tool was possible thanks to the 25% research time at Doyensec. Tune in again for new episodes.